Reporter’s notebook: Progressive Jews at Columbia try to make it work

It is undeniable that the protest movement at Columbia has a major Jewish component. The encampment seder was not a ploy, nor was the Kabbalat Shabbat service an act.

Note: this article was reported and written on Monday, April 29, prior to students’ seizure of Hamilton Hall and the infiltration of masked men into John Jay residence hall that night.

NEW YORK - Columbia University’s 2pm deadline for student protesters to vacate their tents came and went without a peep. The camp remained in place, and enthusiasm remained high.All around the center of campus, a ring of students marched in laps, chanting the slogans that have brought so much attention to the New York university ever since a student encampment was erected there several weeks ago.The protesters demand that the school divest from Israeli companies and sever ties with Israeli academia.“There is only one solution,” the students chanted. “Intifada, revolution!”“Intifada, intifada!”“No peace on stolen land!”It was clear from the outset that the demonstrations at Columbia were not anti-war, and they certainly were not pro-peace; the slogans chanted were explicitly in praise of the “resistance,” with no qualification, and despite the media’s focus on a ceasefire, I’m not sure I heard that word one time.

Summer camp for activists

The encampment itself, however, had the environment of a summer camp, or a music festival. Olivia Reingold described it in the Free Press as “Columbia’s Communist Coachella”– another comparison could be the Supernova music festival, minus the bullets and grenades [aimed at the participants by Hamas terrorists].At the encampment, I saw shirts reading “ceasefire now” and “not in our name.” I saw a table prepared for observant Jews, with boxes of matzah and no leavened bread. And I saw a tent labeled “Ethiopian Jews for a Free Palestine,” with a Hebrew message that – unlike the now-infamous JVP Seder plate at another university – was written right-to-left, as Hebrew always is.It is undeniable that the protest movement at Columbia has a major Jewish component. The encampment Seder was not a ploy, nor was the Kabbalat Shabbat service an act. Anti-Zionism is a major part of many progressive Jewish spaces in the United States now, and groups like IfNotNow, which launched in the wake of Operation Protective Edge in 2014, have been remarkably successful at changing the narrative for young Jews on campus.It also important to note that, at least in my short time on campus, not all visibly Jewish students reported fearing for their safety; despite the sincere concern many students have about where things might go in the future, I spoke with one student who wears a large kippah and a striking pair of loose peyot, and he confirmed that no one had given him any trouble.

At the same time, students who were outspoken against antisemitism did report being spat on, harassed, and assaulted. “The trifecta,” one student called it, reporting that he knew a number of other students who have been subjected to all three in the last six months.But to say the campus is not (visibly, at least) a clear and present danger is not to say that no one feels scared – many Jewish students have left campus altogether, and another student told me he is careful to avoid the encampment area at night. The more immediate concern, though, is what that same student called “a psychological deterioration,” echoing reports I heard from other Jewish students about a blow to their mental health.Few at Columbia seem to believe that all Jews everywhere are guilty for who they are – protest leaders have embraced Jews who share their politics, as they are wont to point out – but it is hard to shout “victory for the resistance,” or so strenuously avoid a call for the unconditional release of hostages – unless you are okay with some Jews being killed for who they are, as long as who they are is Israeli.And so a breakdown or two should be expected, I think, among students who bear some connection to Israel; how else should they feel, when calls to “globalize the intifada” are commonplace?

"There is only one solution: Intifada, revolution!"

One hears that word, intifada, more often than one hears “ceasefire” at Columbia, and its use dwarfs that of “peace,” which is almost nonexistent.The word means “uprising,” or “shaking off” in Arabic, and it is associated in every Israeli’s memory with waves of terrorism against civilians, killing hundreds on buses, cafés, and crowded markets.Omer Lubaton Granot, an Israeli graduate student pursuing a Master’s in Public Administration, told me about those times: “I grew up in the shadow of the two intifadas in Israel,” he said “I was born [during] the first one, and [during] the second one I was 11, 12. We lost family members.”And it wouldn’t be the last time Granot had his family torn by Palestinian terrorism: “I have relatives who were taken hostage in October,” he told me, “and returned in the deal in November.” The Israeli-American, who has lived in New York for two years now, is a leader in the Hostage and Missing Families’ Forum in the city.I noticed as I spoke with him that the now-iconic ‘kidnapped’ posters, depicting Israelis held captive under Gaza, were spread across one campus surface just behind where Granot’s child was playing in a field of little Israeli flags.

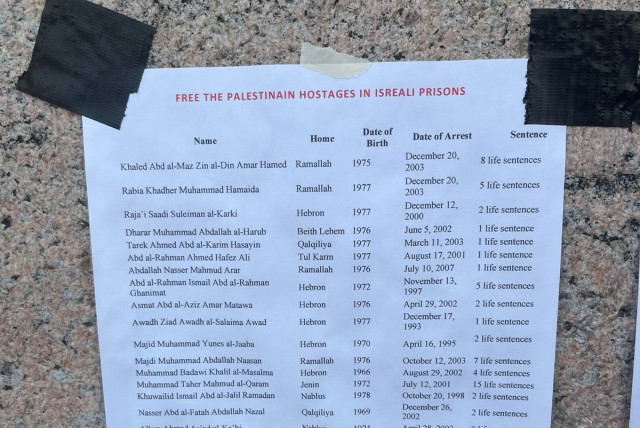

A curious "hostages" list

A few meters away, someone had affixed a list of “PALESTINAIN (sic) HOSTAGES IN ISREALI (sic) PRISONS,” and I noticed that everyone on the list had been tried, convicted, and sent to prison – their punishment was listed with their name, and it was usually at least one life sentence.A bit of Googling once I got home revealed it was not a list of Palestinians currently detained in Israel, nor was it a list of supposed wrongful-convictions: the list, bizarrely, was of the Palestinian prisoners exchanged for Gilad Shalit in 2011 – these were men who had murdered yeshiva students, made bombs and plotted abductions, smuggled suicide belts into Israel, blown up buses, and stabbed Israeli civilians.Granot, familiar with that sort of terrorism, had no patience for sympathetic chants, he told me.“When people are chanting here, ‘Globalize the intifada,’ or ‘From the river to the sea, Palestine will be Arab’” – a chant I myself heard outside the campus, which is only ever said in Arabic – “we Israelis know exactly what that means.”“Do you think they know what it means?” I asked him. It is clear from talking to many participants that their familiarity with the conflict is superficial at best.“You know, I hear a lot of people asking that,” Granot told me. “But we’re talking about adults who study at the most prestigious institutions in the world; we should hold them accountable, and if they do not understand, they should also bear the consequences of what they say.”

'Definitional anxieties'

I spent most of my time on campus, though, speaking with a small group of students who took issue with the media’s fixation on Columbia, a burst of attention they said was unhelpful, disruptive – and, they said, noticeably silent on anti-Muslim hate crimes, of which they gave several examples.The students, all women, were mostly Jewish, with day school or summer camp educations. They were active in the local community, and had family ties to Israel, where they’d spent time. They were also, as one of them put it, “dedicated to Jewish community and also dedicated to justice.”I asked one of them, who had spent time at the encampment and planned to return, what she thought of calls for “intifada.” I wanted to know if she chanted it herself, or was comfortable standing next to those who did. And I wanted to know what she understood it to mean.“That’s something that I think progressive Jews who have been hanging around the encampment,” she said, “are really working through – these mistranslations, and these definitional anxieties. They hear ‘globalize the intifada, and think about their uncle, who was killed in the intifada.’”“Those are very real fears and real emotions,” that student said. “And,” she continued, “there is a real understanding of the intifada as a more” – she paused to find the right word – “metaphorical representation of liberation.”A similar exchange ensued when I asked the group what Israelis should think about the fact that Students for Justice in Palestine and Within Our Lifetime – two of the groups at the heart of the national protest movement – have praised October 7.“What do you consider praising October 7?” One of them asked me. “I’ve seen both of those statements, the initial ones, and I’m not sure I could qualify that as praise.”When I got home, I did a little Googling: on October 9, Columbia Students for Justice in Palestine, in a statement cosigned by Jewish Voice for Peace, called the then-ongoing attack – it took several days for Israel to fully recapture the Gaza border communities invaded by Hamas – ”an unprecedented historic moment for the Palestinians of Gaza,” declaring their “full solidarity with Palestinian resistance.”

A depressing reality check for an ally of the cause

One of the progressive Jewish students I spoke to told a story of her attempt, several weeks ago, to express her solidarity with Gazan civilians, who— at time of writing— are overwhelmingly displaced, some malnourished, and many thousands of whom have been killed; the student was upset by these facts, as were many of those I talked to.

“I’d heard about a havdalah,” she said, “organized by a ‘Jews for a ceasefire’ group. “I felt compelled to go.” It was happening outside Columbia, just beyond where the main group of off-campus protesters were gathered. “I ended up trying to go to havdalah,” she told me, “and I ended up in the middle of the most violently antisemitic chants I’ve ever heard in my life.

“I heard, ‘brick by brick, wall by wall, we will make Israel fall,’” she told me, “immediately followed by ‘From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.’

This student had never taken issue with the “river to the sea” chant, she said, acknowledging that different people bring different intentions to the phrase. “But immediately preceded by ‘brick by brick, wall by wall,’ that feels extremely, extremely problematic.” Protesters had also chanted to burn Tel Aviv, she told me.

“I stood there for a good twenty minutes, and I felt so uncomfortable and so alone. Especially because I had gone with the intention of trying to show my solidarity in a Jewish way.”

But, she said, “I needed to hear that. I think I had [misunderstood] the movement and its friendliness to Jews, putting it on some pedestal, some weird exception where I didn’t care that they were being so antisemitic.

“I needed someone to look me in the eye, and tell me, ‘Israel will fall.’”

My takeaways from an afternoon on campus

As of Monday afternoon, Columbia did not appear under siege. Once the main protests died down, the scene turned remarkably calm. The encampment itself is negligible in terms of the space it takes up on campus – the reason its location has been such a fight is that it is pitched precisely where Columbia intends to hold its commencement in two weeks.But not all protests are created equal, and this one – whether a clear and present danger to Jewish survival or not – is morally indefensible. Rape is not resistance, terrorists are not hostages, and a nonviolent movement does not chant for “intifada” while never once calling for peace.I’m sure there are many students who are there for community, for a cause, to do the right thing.But as Omer, of the hostage families’ forum, correctly pointed out: these are adults. They are responsible for their actions, and they are responsible for their words.If Columbia students want to do something to save the lives of Palestinians – a noble cause, no doubt – they can begin by leaving a movement that celebrates the monstrous attack that started this war in October, and make for themselves another movement, that actually wants to end it.

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });