Arthur Szyk: The Zionism of the artist of the Jewish people

On the 75th anniversary of the resurrection of the Jewish state in the Land of Israel, it is Szyk’s unwavering and enduring love of Israel which serves as a model of perpetual devotion and action.

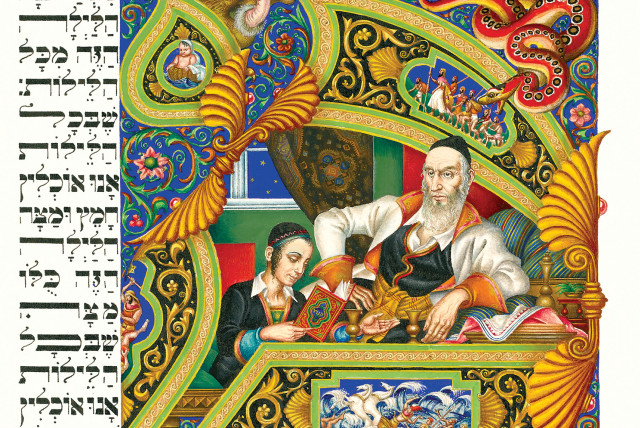

Arthur Szyk begins his illustrated Haggadah by inscribing on its decorative frontispiece “If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right hand wither.” The ancient psalmist’s promise became a personal pledge for Szyk which flowed through his ink and blood.

In a mid-1930s pen and ink self-portrait, these words appear with the artist placing his right hand over his heart, symbolically swearing eternal loyalty to the Jewish people and Jerusalem. (This artwork also paid tribute to the Polish cities of Łódź and Lviv, whose Jewish populations supported his creation of the Haggadah.)

For the “soldier in art,” as he called himself, Szyk’s right hand was the means by which he forged his art to fight on behalf of the people of Israel. For the artist and the man, his right hand was literally his very essence. It was his lifeline. It was the physical manifestation of his soul. Should it wither, it would be the end of Szyk himself. Therefore, when he penned these words, his wholeness, his entire being was at stake if he did not “place Jerusalem among his highest joys.”

Fifteen years ago, I traveled to Israel to exhibit my newly published edition of The Szyk Haggadah at the Jerusalem International Book Fair. The focus was to reintroduce his Haggadah to a new generation of Israelis, since the first vellum edition appeared in 1940 in London, and the first popular edition was published in Israel in 1956. As I stood behind the showcase in my booth at Binyenei Ha’uma featuring an opened copy of Szyk’s Haggadah for passersby to catch a glimpse of the brilliance of an illuminated page melded with Hebrew text, I was approached by a man I will never forget.

You have seen this type of man before, but you have never heard what this particular man said to me. He wore the longest black coat, with the blackest black hat, and the fullest black beard. As he looked at the glass showcase featuring Szyk’s Haggadah, he said to me in perfect English: “That is the Haggadah of Arthur Szyk, correct?”

He was from an anti-Zionist Hassidic sect, Toldos Aharon. I was not only astonished that he spoke to me but that he recognized the Haggadah as Szyk’s. And then he leaned-in closer and asked, “May I tell you something?”

“Yes, of course,” I replied.

“I know that Arthur Szyk was not an observant Jew,” he paused, “but, every time I look at the Hebrew calligraphy in his Haggadah, I know that he was a man with a deep Jewish soul.”

This one line from one such anonymous religious man validated what I have always believed – that Szyk’s soul, his essence, his art, his hand, his heart, has the power not only to touch one man so very different from him but to touch so many kinds of Jews over 120 years since his birth. I am certain my visitor also knew that Szyk was a passionate Zionist.

This story captures for me why Arthur Szyk is the artist of the Jewish people and why his art articulates the ability to touch and connect with all Jews – from those secular Jews who observe Passover and love Israel, to those religious Jews who prefer not to call Israel its Jewish state, and those Jews in between.

Arthur Szyk: The artist of the Jewish people

On the 75th anniversary of the resurrection of the Jewish state in the Land of Israel, it is Szyk’s unwavering and enduring love of Israel which serves as a model of perpetual devotion and action on behalf of the Jewish people. As a Jew, he had worn his Jewishness proudly on his sleeve. Every Pole knew it when he served as Poland’s director of art propaganda in its war with the Soviet Union following World War I. Szyk never compromised his being a Jew, and he was respected for it. As a Polish Jew in France in the 1920s, where he was befriended by Vladimir Jabotinsky and illustrated some of his writings, he affirmed his Jewishness before the French public by unabashedly creating drawings for several Zionist novels including Pierre Benoit’s Le Puit de Jacob and Ludwig Lewisohn’s Last Days of Shylock, in addition to his illuminated Megillat Esther and Statut de Kalisz in defense of Jewish survival, integrity and sovereignty. In his completed Haggadah Dedication page to King George VI in 1936, Szyk boldly challenged authority by calling for an exodus of European Jews to Palestine in the face of British White Papers restricting his people’s immigration to their homeland. In that same year, he painted Joseph Trumpeldor at Tel Hai, amidst the Arab riots taking place in Jerusalem – reminding Jews of the heroism of the past and informing them of needed courageous action in the present. In London, while supervising the printing of his Haggadah (1937-1940), his anti-Hitler and anti-Stalin artworks commenced, soliciting world support against an alliance of evil. In early 1940, he saw himself as a spokesperson for Polish Jewry and its refugees, serving as president of the Association of Jewish Polish Citizens in Great Britain. Szyk was a relentless activist on behalf of his people.

With his arrival as an immigrant to the United States in late 1940 (sent by the British and the Polish-government-in-exile in London to bring the face of the war in Europe to the American public), Szyk, the Polish Jew, became the most important anti-Nazi artist in America and the leading artist for the rescue of European Jewry. In one drawing in 1943, titled Palestine Restricted, we see huddled and fearful Jews crowded up against the White Paper padlock on the gate to Palestine as the Nazi vulture with talons outstretched swoops in on the unprotected. Among them is a fallen resistance fighter, rifle in hand, lying on his back; within his armband marked “Jude” with the star of David, Szyk has penned his name, literally identifying with the tragedy and courage of his people. Tears fall upon his cheek.

To give strength to his personal mission, Szyk joined forces to fight collectively as an integral member of Peter Bergson’s (aka Hillel Kook) groups in America, advocating for saving Europe’s Jews. He was a collaborator with Ben Hecht, who in his autobiography paid tribute to the artist, stating: “How or why Arthur Szyk became our one-man art department I never found out. He appeared among us one day like a bonanza on the doorstep. Thereafter, he illustrated all the ads I wrote (for the American press). He drew program covers for all the pageants I invented. He drew posters and pictures for throwaways at rallies, for invitations to shake-down dinners. He worked for eight years without pause. Nobody paid him anything and nobody thought of thanking him. Nor was he an unknown artist using a Cause to add luster to his name. It was already one of the most illustrious names in international art.”

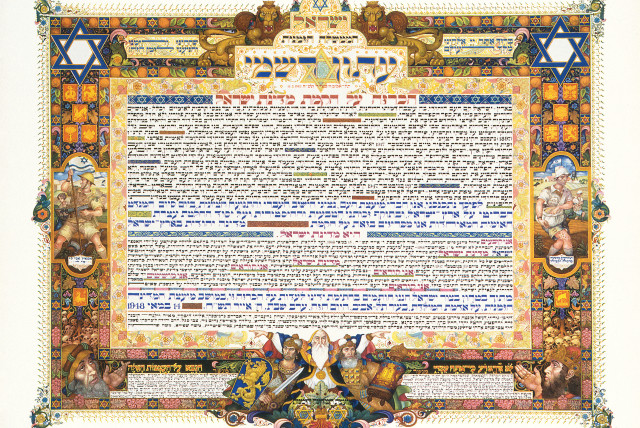

When Jewish statehood was declared, Szyk’s wife, Julia, would write in her memoirs: “We were at home with some friends and heard the news over the radio. Arthur cried for joy. It was a dream of his that had come true. He was the happiest man in the world. He sat down the next day and made the Declaration of Independence of Israel. It was a magnificent scroll with all the dreams of (his) youth. Palestine was always his personal concern. Those who fought for it were like his own children. He felt like they belonged to him.”

Before and after the War of Independence, Szyk’s right hand would take on the British manipulation of the Jews and Arabs of Palestine and England’s roadblocks to a Jewish state. His Israeli soldiers would defend their affirmed homeland against the Arabs, Szyk going so far as to state, “An Arab Jerusalem is as absurd as a Jewish Mecca.”

When the war was over, Szyk would not only use his right hand but also take up arms against the United Nations and its endless attacks on the Jewish state, calling the UN “Security” Council a mockery.

In 1948, the immigrant Szyk became an American citizen. Two years later, he illuminated the Declaration of Independence of the United States. On July 4, 1950, this proud Polish Jew stood before hundreds of people celebrating him in front of New Canaan, Connecticut’s town hall, the chairman of the event calling him “one of the world’s great free men.” In his home, Szyk hung his Declaration of Independence side by side with his Declaration of Israel’s Independence.

Szyk had moved to Connecticut, where he lived and worked the last five years of his life, dying in 1951. Menachem Begin would visit him there, while Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann would both sign the Israel Bond Certificate that Szyk prepared to raise funds for the newborn Jewish state. There wasn’t an Israeli leader, president, or prime minister who did not recognize Szyk and his love of the Land of Israel. There is a copy of The Szyk Haggadah in Israel that is signed by virtually all of them.

On the last page of his Haggadah, Szyk concluded it with the same words as he inscribed on its first page: “If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right hand wither.” But here he added a message defining himself, writing, “I am but a Jew praying in art. If I have succeeded in any measure, if I have gained the power of reception among the elite of the world, then I owe it all to the teachings, traditions, and eternal virtues of my people.” It was signed within a handwritten seal: “Arthur Szyk, Imagier d’Israel,” – “Arthur Szyk, painter of Israel” – the artist of the Jewish people. ■

Irvin Ungar’s book Arthur Szyk: Soldier in Art was a winner of the 2017 National Jewish Book Award; his book Arthur Szyk Preserved: Institutional Collections of Original Art has just been released; and his memoirs on his life with Arthur Szyk have been accepted by a major US university press and will be forthcoming. His essay “Freedom Illuminated: My journey with The Szyk Haggadah” was the cover story of the April 22, 2019, issue of The Jerusalem Report.

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });