What are 'protected Jews'? A glimpse into the Austrian exhibition in Burgenland

What could this mean for whole communities of Jews, and what is the implication of being unprotected?

What are protected Jewish communities? The very word “protected” is laden with associations of the modern area. What could this mean for whole communities of Jews, and what is the implication of being unprotected?

These are questions that come to mind in light of the newly revealed materials being shown in the exhibition “Schewa Kehilot” – the Seven Jewish Communities under the Esterházy Princes (1612-1848) –at the Esterházy Palace of Eisenstadt, Austria.

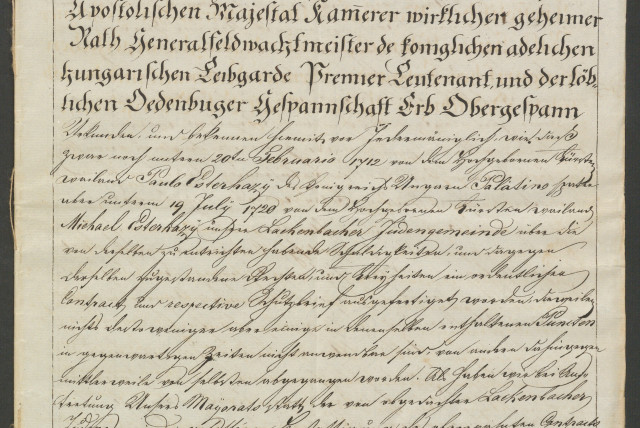

The exhibition is devoted to Jewish life under the patronage of the Esterházy princely family. It includes little-known or researched aspects of Jewish history. Previously largely unknown historical documents and publications, plans, maps, and objects are also on display.

It peeks into the daily lives of Jews who lived in the communities that became known as Burgenland, where Jewish communities were permitted to live during the era of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Now in southeastern Austria, bordering on western Hungary, Burgenland was originally in Hungary. The Seven Communities were noted for their outstanding yeshivot and eminent rabbis.

“Schewa Kehilot” opened in June 2022 when it was presented as the annual exhibition for 2022. That run was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to close in October of last year, it proved to be of great interest, so the Esterházy Foundation recently decided to make it a permanent exhibition.

My paternal family came from Mattersdorf in this region, having settled there after the 1492 Spanish Expulsion. I was curious to learn how my antecedents lived during part of that time.

Intricate involvement in daily life

This exhibition draws on the well-organized estate chancellery in Eisenstadt and the central estate management documents in Vienna to cull an array of items that answer “diverse bureaucratic demands… including official protocols, land registers, and accounts of princely audit offices.”

Also included are descriptions from conscription lists; contracts between the estate and communities or individuals, affecting particulars of life, such as building plans, requests to enlarge cemeteries, applications for permission to marry; and further reaches into more aspects of daily life that provide us with a “vivid picture of the Jewish communities in present-day Burgenland,” according to the catalog.

The exhibition catalog explains the origins of the royal protection of the communities of Western Hungary in the mid-1600s when the future Count Nikolaus recognized good relations with the Jewish communities (starting in 1618 with his holdings in Landsee-Lackenbach) as having “importance for the economic life of his estates.” In 1627, he formalized the arrangement of being a patron of Eisenstadt and Mattersdorf (known as Mattersburg after 1924) in a Schutzbrief (letter of protection).

With Prince Paul I of Esteraházy’s acquisition of the small Kobersdorf community in 1704, he became the protector of eight Jewish communities. Against a backdrop of a rampant plague in 1739, the Neufeld protectorate was dissolved, and its members were distributed among the remaining Seven protected Jewish Communities, known as the Sieben-Gemeinden in German.

This start of a mutually beneficial relationship of protection and regulated Jewish communal life experienced numerous changes in royal succession; church-connected influence; repercussions from the Kuruc revolt of insurgents against the Hapsburgs of 1704; and wider politics that affected the broader communities in documented particulars. It kept the tax-paying Jews subject to whims and inconveniences, both major and minor, from the all-powerful royals.

The exhibition catalog is divided into nine sections and displays a map of the Burgenland region during that period, including the Seven Communities, as well as 10 biographies of significant figures, and a time line that starts with a Jewish presence mentioned in the 1373 Eisenstadt town charter. Archaeological evidence of a Jewish presence in Austria as far back as the third century CE was uncovered in the form of an amulet containing the Shema prayer, discovered in 2013.

The time line ends in 1848. With the end of the feudal period and the rise of the Enlightenment, the state assumed some of the protections – such as freedom of religion – that arose during the Age of Reason.

Acquiring protection and life within it

The exhibition section titled “Payment for Protection” describes the application process for a group of Jews to be able to join a protected community. Representatives of the applicants and the Esterházy estate would meet. If accepted, a letter of protection would be issued, listing agreed-upon points, especially regarding levies and payments.

For example, in 1690 a group of 20 Jewish families from the Moravian town of Nikolsburg applied to live in Eisenstadt; each family was required to pay six gulden in protection money. The value of one gulden at the time could purchase 17 kg. of bread. This was a significant sum for families struggling to make a living at a time when Jews were very restricted in occupation choices.

In the section addressing the economy, the catalog describes the range of limitations. Since the Middle Ages, Jews were prevented from engaging in various trades: they could neither join artisanal guilds nor farm the land. Jews could only pursue their livelihood in professions deemed necessary to the community such as tailors, shoemakers, bakers, butchers, glaziers, brewers, or distillers, or serve as moneylenders. This varied in some of the protected communities, with notable individual exceptions.

Benefits to the Jewish protected towns included the ability to live their lives in accordance with their beliefs. All the infrastructure necessary to maintain religious life was the responsibility of the Jewish community. Each town had a synagogue, mikveh, and schools (the wealthy hired tutors), as well as cemetery grounds.

Larger communities had Spitaler – old age and nursing homes – and shelters for the poor. Princely estates would approve the communal needs and be involved in designating the sites and supervising those whose permits were granted.

Permission for a wire Shabbat enclosure was generally granted, although a special levy was required to be able to erect a barrier. In the 17th century, permission was refused in Frauenkirchen, to avoid inconvenience to Christian pilgrims carrying banners who would need to lower them to pass under the wire enclosure. Kosher butchers provided for the Jewish community’s needs and there was cooperation with non-Jewish butchers who would use the parts of the animal that could not be kashered, and would otherwise go to waste.

From 1739, there was a yeshiva in each of the Seven Communities: Kitsee, Frauenkirchen, Eisenstadt, Mattersdorf, Kobersdorf, Lackenbach, and Deutschkreutz. The Jewish community was obligated to provide lodging and meals for nonresident students. Well-known rabbis attracted many students who were supported in this way by their fellow townspeople.

Tensions existed between Jews and Christians in the wine and leather trades, in the practice of maintaining toll stations, in the area of residential rentals, and in the imposition of Jewish marriage restrictions, etc., as evidenced by the documents on display.

The decades-long custom of the Seven Communities to give gifts to the princely family and other high officials of the primogeniture for the New Year, Easter, and St. Martin’s Days is noted by the ruler (in the case of Prince Nikolaus I Esterházy in 1777), who waived the gifts in addition to not raising taxes during his reign.

This was in response to a petition from the Jewish community, which needed to raise 425 gulden to cover these gifts in 1776 – literally a lot of “bread” (according to the 1690 example and in the modern slang connotation). That year is likely to ring a bell as the year of the signing of the American Declaration of Independence, the beginning of the United States of America, and the break with British royalty.

Jewish life in the Seven Communities seems to have been a delicate tightrope walk. The deal struck meant that they could adhere to Jewish religious strictures and observe as they believed, while on the other hand, they were under pressure to make a living for self-support and enough for extra levies. Additionally, the Jews had to take care not to raise the ire of neighbors, who could invoke unwelcome legal proceedings.

Take the curious case of the 1819 investigation and impoundment of six mikveh tubs. After expert testimony was given that they were for ritual and not commercial use, the tubs were reinstalled. One wonders how this impacted family life in the Seven Communities.

The exhibition does not lead one to wonder what the advantages of protected status were. The explicit facsimile of an 1848 lithograph titled Terrible Mistreatment and Persecution of Jews in Pressburg on April 24, 1848 shows men and boys beating bearded Jews, and a woman wearing a head covering who is protecting a baby lying on the street. The lithograph is by 19th-century artist B. Bochmann-Hohmann on loan from the Wien Museum in Vienna.

The lithograph depicts the violence that took place on the day after Easter Sunday in 1848. Traditionally, Easter is associated with a passion play. These often evoked antisemitic sentiments against the Jews, who were deemed “Christ-killers.” The connection between Easter and a potential for violence against Jews was a known propensity well into the 20th century, according to my Austrian-born father, Alexander Breuer (1926-1983), who recalled the need for extra caution at that season.

Women and the protected communities

In one of the few mentions of Jewish women in the exhibition, a kitchen accident from hot fat spilled by Barbara Risz in 1830 caused a major conflagration. The punishment for “criminal acts and negligence” was banishment for her and her husband’s entire family from the protected Kitsee community.

Of the 10 selected personalities highlighted in the exhibition, notable is Baroness Fanny von Arnstein, from a wealthy Jewish Berlin family who settled in Vienna in 1777, after marriage to her financier husband. In the spirit of the Enlightenment, she was the first Jewish woman to conduct a literary salon, where she pursued interests in politics, social issues, and culture, particularly music. In the new spirit of the times and her social circles, she did not wear a head covering.

Arnstein was concerned about the overcrowded conditions in the Seven Communities resulting from the policy that Prince Nicholaus II Esterházy tried to enforce, aiming to separate the Jewish residents from their Christian neighbors. She tried to intercede, especially in the case of Mattersdorf, and her three-page letter from 1815 asking the prince to lift the ban on Jews living in Christian houses is on display.

She succeeded in getting approval for 12 new buildings in today’s Angergasse, thus somewhat easing the tight residential space in Mattersdorf, although she died before seeing it actualized. As a wealthy Jew active in the highest Viennese social circles – at a time when many Jews preferred to downplay their heritage and conversion from Judaism was perceived as a step toward facilitating higher social standing – her intercession on behalf of fellow Jews stood out.

The catalog, although dealing with Jewish life in the century before the rise of Hitler and Nazism, touches on the later harsh reality. Arnstein died in 1818 and was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Währing, Vienna.

Persecution even in death came to the Arnstein and Eskeles (her sister’s family by marriage) families when their graves were desecrated during World War II. Their bones were removed and transferred to the Natural History Museum in Vienna, for “scientific purposes,” states the catalog.

It wasn’t until 1947 that the museum skeletons returned to the Jewish community for reburial in family plots. By then, it was no longer possible to know their exact identities for individual reinterment.

The bulk of the items displayed are from the Esterházy Foundation. The exhibition also includes images and artifacts on loan from the Hebrew Union College Cincinnati; the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien; the Wien Museum; the Austrian National Library; the Tobler Print Collection; the Esterházy private collection of the Eisenstadt Palace; and the Forchtenstein Castle. Some of the exhibited pieces are facsimiles.

Lovers of traditional portraiture in the classical approach to painting in Western art will find examples on display. Laboriously detailed illustrations, engravings, and lithographs are included in the exhibition, and it is worth remembering that they were created prior to the invention of the camera, let alone the cell phone.

Admirers of elegant calligraphy of yore, such as quaint renditions of the maps that were guides for town planners, will find much to be charmed by. Now as we view them from the age of AI-generated designs and computerized accuracy used to aid architects and engineers, our eyes may find these maps and documents most remarkable as curios of history, and remind us from whence we have come, historically and technologically.

Reactions and impact of the exhibition

The exhibition is curated by Felix Tobler, who after 30 years of research in this area and many publications, was the “ideal historian to generate the content,” wrote co-curator Margit Kopp. Tobler also wrote the catalog text – and co-curator Florian T. Bayer completed the team. There has been a great deal of interest “among Jewish communities worldwide,” says Kopp. “We were able to welcome visitors from Austria, Germany, Denmark, Israel, America here,” along with individual guests from various countries who see it while visiting the castle.

In response to the Magazine’s inquiry, the curators each described the reactions they observed. Tobler described the impact as showing ”interest and wonder.” Co-curator Kopp sensed viewers as “being touched,” and her co-curator Bayer said they were “questioning, searching, and quiet.”

Very few school classes have visited the exhibition, which is understandable given the “long advance planning phase necessary” in incorporating content into the educational system. As Kopp pointed out, “We are only in the second year of the exhibition.” Further, there has also been a dearth of visitors to the exhibition from the immediate surrounding regions.

Kopp continued, “The Esterházy Private Foundation has nevertheless, and precisely because of this, decided to make the exhibition, which was actually planned for only four months in 2022, into a permanent exhibition. The private foundation is also looking for partner museums abroad, such as in the US, Israel, and Hungary, in order to be able to show it [to a wider public] during the winter closing times,” as in Bavaria.

The exhibition is continuing in the Moreau Hall of the palace – “one of the most beautiful Baroque palaces in Austria,” as described on its website – until the end of October 2023. Thereafter, it may be exhibited in a different part of the palace, in an adjacent building, or abroad as a traveling exhibition.

Seven Communities and local connections

I believe that there are no coincidences, something that was evidenced when a tangible link to the Seven Communities fell into my lap about this time last year. I unpacked a box and came across my grandfather Adolph Breuer’s book of penitential prayers for the week before Yom Kippur, his book of Slihot.

It had traveled all the way from my grandparents’ hands to mine over three continents, only to be opened just as I had learned of the Zwebner connection to Kobersdorf. I held my grandfather’s book, signed by his hand, and bearing the stamp of the long-gone Kobersdorf Jewish bookstore.

My grandfather, Adolf Aharon Eliezer Breuer (1886 Mattersburg/Matterdorf-1973 Monsey, New York), was one of eight siblings and served in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I. Despite his patriotism – family lore holds that he was awarded an Iron Cross – it was only thanks to the courage of my grandmother, Helen Ilona Sarah Just Breuer (1898 Piestany, Czechoslovakia-1972 New York), that he survived the Holocaust. Like many Austrian Hausfrauen (homemakers) of her time, she was catapulted from the traditional patriarchic share of women’s duties of Kochen und Kinder (cooking and children) to find within themselves the strength to demand the release of their husbands from the Gestapo officials. She did so and successfully extracted him from Dachau. This was still early in the war.

Living as we do in a world with near-instant communication, the end of a thread can lead us to what becomes obvious after the fact. I learned of the restoration of the Kobersdorf synagogue from an article by Emmy Leah Zitter in Mishpacha magazine, a world away, only to be led to my relative by marriage, David Zwebner, who lives mere blocks from me.

There is a direct link between Jerusalem and the small town of Kobersdorf. My neighbor and relative, Jerusalemite David Zwebner, is a great-grandson of Rabbi Avraham Shaag-Zwebner, who was known as the Rav of Kobersdorf. Born in 1801 in Freistadt, Hungary, the rabbi was a disciple of the renowned Chatam Sofer. An accomplished rabbi, he built a significant community in Kobersdorf, dedicated the synagogue in 1860, and spoke out to strengthen the Jewish communities in Hungary and in Austria.

“He was said to yearn his entire life to live in the holiness of Jerusalem,” David Zwebner told me as we sat in his sukkah last fall.

He explained, “When my great-grandfather was already in his 70s, there was a change in the political situation, which allowed some Jews to enter the area.” At the time, the Holy Land was within Greater Syria, which was ruled by the Ottoman Empire. Due to changes resulting from the Crimean War, there was a narrow window when Jews could enter the Land of Israel. Shaag, his family, and his disciple Rav Yosef Haim Sonnenfeld, also of Kobersdorf, came over at that time.

In 1873, they arrived in Jerusalem, and desiring to live as close as possible to the holiest place, the Temple Mount, Shaag went to pray at the Hurva Synagogue of the old yishuv in Jerusalem. Zwebner added, “For the ‘great’ of the community, they were honored with a pillar in the Hurva.” The text on the pillar references the two books of Jewish knowledge that he wrote.

In Sonnenfeld’s will, he asked to be buried alongside his rav. “The graves were well maintained when i first saw them with a cousin after the 1967 Six Day War; unlike many others,” said Zwebner. Shaag lived in the Muslim Quarter and was highly regarded by his Muslim neighbors.

Every year on Tisha B’Av (the fast day commemorating the destruction of the Temples and other disasters), Zwebner takes his grandchildren to visit the graves of the two, who are buried side by side on the Mount of Olives. Zwebner said, “They were neighbors generations back, and now for eternity.”

While celebrating the marriage of their son in Prague in 2003, Zwebner and his wife, Ronit, paid a spontaneous visit to his grandfather’s town. Several phone calls in Eisenstadt led them to the key holder of the Kobersdorf synagogue.

The Kobersdorf site is one of only two synagogues – and the only free-standing one – in Burgenland that remains after the 1938 Anschluss (the joining of Germany and Austria by force). The interior was destroyed, like those of so many synagogues in Germany, Austria, and other places on Kristallnacht in November 1938. During their visit, the Zwebners learned that the synagogue had been purchased by a group of non-Jews who intended to restore it, called the Association for the Preservation and Cultural Use of the Synagogue in Kobersdorf.

Since the war years eradicated the Jewish community, although the synagogue has been restored and updated, it is now in use for cultural events but not Jewish religious services. While remnants of its original glory can be glimpsed, the Torah Ark is empty of its original collection of the 13 Torah scrolls used by the once vibrant community.

A prized heirloom of Zwebner’s is his great-grandfather’s etrog box that was passed through the family for generations. It takes pride of place in his sukkah every year.

Zwebner’s support of synagogue life in Austria segued with his interest in synagogues in Beit Shemesh and Ashkelon, where he also maintains a home. He has delved deeply into the history of his community and recently wrote The Founding of Modern Ashkelon by South African Jewry.

Mattersdorf relocates to Jerusalem via New York

Many individuals who originated in the Seven Communities of Burgenland restarted life in Israel. Among the best-known enclaves is the ultra-Orthodox neighborhood of Mattersdorf in Jerusalem.

Kiryat Mattersdorf is located on the northern edge of the Jerusalem Hills. It is named after Mattersburg/Mattersdorf, the Austrian town with Jewish history reaching at least as far back as the 11th century.

It was founded in 1958 by the Mattersdorfer Rav, Rabbi Shmuel Ehrenfeld, whose ancestors had served as rabbis of the Austrian town of Nagymarton (later Mattersdorf, now Mattersburg) for centuries, starting with his great-great-grandfather, the Chatam Sofer, in 1798.

With the 1938 Anschluss annexing Austria to the Third Reich of Germany, the community was evicted. According to Yitzhok Cohen in a 2009 article in HaModia magazine, on March 12, 1938, German soldiers raided the Mattersdorf synagogue during services and ripped the prayer shawls off the worshipers. The German commander warned Ehrenfeld that unless the 4,000 Jews in the district left immediately, they would all be killed. After efforts to help relocate community members to greater safety, Ehrenfeld escaped with his family to America, where they arrived on September 13, 1938.

The Mattersdorfer Rav reestablished his yeshiva in New York, first in the Lower East Side and later in Boro Park, Brooklyn. In 1958, accompanied by Rabbi Avrum Mayer Israel, he purchased land and established a new neighborhood in commemoration of the Seven Communities of Burgenland – Mattersdorf among them – that had been destroyed by the Nazis. This was on the 10th anniversary of the establishment of Israel. Kiryat Mattersdorf was the first neighborhood built in northern Jerusalem, on the city’s northern border, which was situated across from Jordanian strongholds in present-day Ramot. The first apartments were ready for occupancy in May 1965. – H.B.A. ■

Visitors are advised to check the website of the Esterházy Palace to confirm times and location: esterhazy.at/en/exhibitions/schewa-kehilot-en.

The writer is an artist and writer living in Jerusalem. Her graphic memoir, Life-Tumbled Shards, was published in 2023. She can be reached at heddyabramowitz@gmail.com.

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });