A rabbi’s debut novel imagines a black hole swallowing Israel. And then things get weird.

In his debut novel Next Stop, Rabbi Benjamin Resnick crafts a chilling dystopia set in a future where Jews are once again confined to ghettos and threatened by a surveillance state.

Once upon a time, in another century, Benjamin Resnick weaved a fantasy of American Jewish life very different from the story he tells in “Next Stop,” his dystopian debut novel published on Tuesday.

Young Benjamin was a kindergarten student, growing up in Chicago. He dictated a story to his teacher “about how there was this thing called the Jewish bakery and it had the best cookies in the world, and only the Jewish kids could go there to have these cookies.”

The first part was true: As a young boy, Resnick loved the chalky cookies his dad would buy him at the kosher bakery. As for the ban on non-Jewish customers? He made that part up.

But Resnick’s fiction had a real-world impact, at least in his kindergarten classroom. When he shared his story of the Jewish bakery with his class of Jews and non-Jews, “there was a trend for like a week of all the kids playing Jewish,” Resnick told the New York Jewish Week. “Some of them were, but they all wanted to be.”

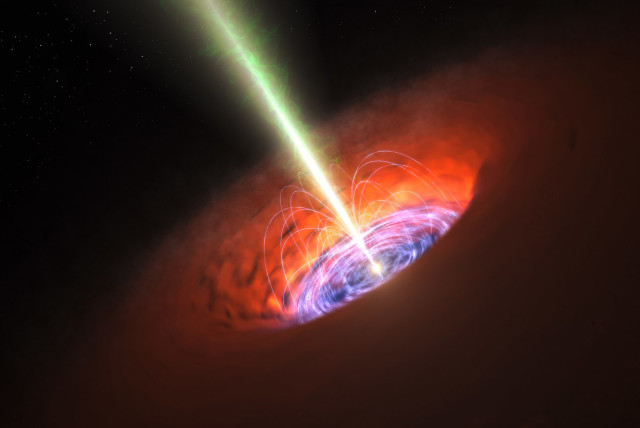

“Next Stop” is set in an unnamed American city at a time when such sweet juvenile Judeophilia is clearly a fading memory. Set 20 years after the COVID-19 epidemic, it imagines a future in which Israel is swallowed up in a black hole in what is called “The Event.” Diaspora Jews are once again confined to urban ghettos, and a young Jewish couple seeks to protect their child from both a surveillance state and armed vigilantes who roam the streets.

The novel arrives in bookstores amid a rise in global antisemitism, a war that has turned the word “Zionist” into a slur on the left, and speculation about the Jewish future captured in a recent cover story in The Atlantic, which declared, “The Golden Age of American Jews is Ending.”

Resnick, 40, the rabbi of the Pelham Jewish Center, a Conservative congregation in the New York suburbs, suspects the Atlantic headline is correct.

“Something has shifted in the American Jewish consciousness,” Resnick said, referring to the Oct. 7 Hamas attack on Israel and its aftermath. “I think it will be remembered as a paradigm shift. I don’t think we’re going to go back to before.”

One way to think of “Next Stop” is as a dystopic next-generation sequel to Resnick’s kindergarten fantasy. The novel’s adult protagonists would have been roughly the ages of his own two young children during the pandemic. In that way, Jewish themes aside, the novel ties into America’s current post-pandemic, pre-apocalypse zeitgeist.

Resnick began the novel in 2021, when he and his wife, Philissa Cramer, moved from Chicago to New York so he could assume the pulpit. (Editor’s note: Cramer, editor-in-chief of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, New York Jewish Week’s partner site, had no role in assigning or editing this article.) Ethan, the first character readers meet, remembers folding paper airplanes with his father during the pandemic — as Resnick and his boys did while they sheltered in a small apartment at the pandemic’s height.

“We cycled through all of these different fixations, and one was paper airplanes,” he said. “There were times when paper was everywhere.”

Resnick wanted to tell a story “about the cyclical nature of antisemitism, and how being Jewish is really fundamentally precarious” — an extrapolation of the passage from the Passover Haggadah that he quotes in the novel’s first seder scene: “Not only once shall they come to destroy us, no, but in every generation.”

What would that look like? What would it mean to be a Jewish American when the American Jewish Golden Age becomes a Bronze or even Dark Age?

To really answer that question, “Israel had to be removed from the board,” Resnick said. And thus the MacGuffin that drives the plot forward and into the fantastic side of literary fiction: the seemingly supernatural “event.” The fictional cataclysm was a conceit that landed very differently on Oct. 7, 2023, just two days after Resnick’s agent submitted the novel to publishers.

“I think Oct. 7 was a profoundly wounding event,” Resnick said. “Obviously, for Israelis, but I think it was a wounding event for Jews everywhere.

“A lot of people who had the volume turned down on their Jewish identity, as [the late Israeli novelist] A.B. Yehoshua puts it, had the volume suddenly turned way up,” he said. “A lot of people who were not as involved in the Jewish community in traditional ways, or who didn’t think of that as a core aspect of their identity woke up to the fact that, ‘Yeah, the world certainly thinks it’s a part of my identity.’”

Coincidentally or not, it’s a journey his protagonist Ethan undergoes as the world of “Next Stop” becomes more and more threatening to its Jews.

Not that Resnick thinks the persecution he imagined in “Next Stop” — Jews banned from restaurants, subways and professions, and from marrying non-Jews — is around the corner. “If I believed that, I wouldn’t be here anymore,” he said.

At its core, “Next Stop” is not a parade of possible horrors, even as it describes a world of app-based antisemitism, wavering politicians and extrapolations of what it would be like if it happened again and here and now.

A fan of fantasy and speculative fiction, Resnick knows the genre tropes of zombies and unicorns and rocket ships are just a way to tell stories about people, albeit in different and perhaps impossible circumstances. So while the premise leads to expectations of “an unrelentingly grim, dark book,” Resnick said early readers report “that it really doesn’t feel that way at all. It has a warmth that makes some of the really challenging material palatable and approachable. And I say that a little bit carefully. Because I do think when you’re writing about horrible things, it should feel horrible.

“At the same time, this book is in many ways a domestic story,” he continued. “It’s a love story and it’s a story about parenting. And in the context of all of that, there are moments of beauty and caring and there are funny parts of the book.”

For Resnick, the beauty is the point — or at least one of the points.

“Fiction can break through some of the endless doomscrolling and the sense that the world is only horrible,” he said. “Fiction can invite readers into other worlds and other ways of perceiving, not always with the goal of consolation — although there is some consolation in the book — but just encountering a well-told, heartfelt story is itself cathartic and meaningful.”

And these are times that call out for relief.

“There was a period there when, in our family household, mom and dad were talking about very little other than the war,” he said. “It was very present for me in my rabbinic work. It was very present for Philissa in her journalistic work. It felt suffocating.”

It led him to ask his wife: “Do the kids know that Daddy actually thinks being Jewish is this wonderful thing? Because all we’re talking about is how awful it is.”

Readers of “Next Stop” will get the sense that Resnick indeed believes a 21st-century Jewish life with traditional Shabbat dinners and seders offers beauty and joy. He notes moments of Jewish ritual life perhaps not captured before by novelists (such as that awkward moment when someone participates in a pre-meal ritual hand-washing for the first time).

Resnick, who trained and worked as a chef before pursuing the rabbinate, was ordained at the Jewish Theological Seminary in 2014, and is currently pursuing a doctorate in Jewish mysticism at JTS.

Balancing a pulpit, his studies, a young family and a writing career, Resnick has a discipline that grounds him: meeting his daily writing goal of 500 words every day (“other than Shabbat”). His productivity secret: Until his daily quota is written, “I basically don’t go to bed.” The act of writing gives him “a sort of heightened attention, and heightened intellectual and emotional stimulation, but also calm.”

Which is not to say that he doesn’t feel his story’s emotions.

“When I’m writing about children, I imagine it for my children, and that can be hard,” he said. “I also like my characters. I don’t tend to write about characters that I find really distasteful, because I don’t want to spend time with them. And sometimes I have villains, but they’re the villains, not the main characters. The main characters are people that are flawed, and feel like real people, but they’re not people that I think are despicable or that are worthy of pain.

“So I don’t like when bad things happen to them,” he added, “but sometimes they do.”

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });