Friendships between Arabs and Jews tested during the war

An unlikely friendship is tested by the war. Can it survive?

Two girls, both 16, sit shoulder to shoulder at a crowded Tel Aviv café. Each wears a cropped sweater, hoop earrings and a gold necklace, one featuring a Star of David, the other a cross.

It’s storming outside – big cracks of thunder, torrents of rain – and at the table the conversation also takes a tempestuous turn.

“October 7 was not about land or the occupation,” says Adar, referencing last year’s deadly attack on Israel. “It was about hating Jews.”

Angelina snorts. Of course it was about land, she says. “I have a question: If someone came to you and said ‘I want half of your house?’ would you be like, ‘Yeah, OK, take it’?”

“Of course not,” says Adar. “But at the end of the day, it wasn’t like the Jews came here from the Holocaust and decided to open up a war. We didn’t have any place to go.”

Just then the waiter approaches and asks if the girls are ready to order. For a moment, they shelve the debate and turn to the question of brunch.

Angelina and Adar are like any friends. They love volleyball. They love shopping. They love Drake. They open up about their families, their boyfriends, their anxieties about the future. They share clips of cute animals and memes.

Friends or enemies?

Unlike many friends, these two Israeli citizens come from opposite sides of one of the world’s most intractable conflicts. Angelina Shakkour is a Christian Arab. Adar Hirak Asaf is Jewish.

For a long time, it didn’t seem to matter that they didn’t always see eye to eye. Then came the brutal Hamas attack and Israel’s retaliatory strikes on the Gaza Strip. As the war deepened and deaths mounted, they watched as other friends became more entrenched in their views. Both admit to sometimes hiding their friendship from family members or others who might judge.

Thanks to the unique program in the United States that brought them together in the first place, Angelina and Adar are unusually skilled at navigating differences of opinion. They had been trained, in fact, for moments like this.

But as the war tore seemingly everything around them apart, a question hovered: Would their friendship survive?

Angelina, who belongs to the community of Arabs who remained inside Israel’s borders after the country was founded in 1948, resides in a small town in the North. Adar lives two hours south in a suburb of Tel Aviv.

THEY MET 11,000 km. away from home at a summer camp in the mountains of northern New Mexico.

Each year, a nonprofit called Tomorrow’s Women flies a group of girls from Israel and the West Bank to Santa Fe for a leadership training course geared at building peace. The program, which emphasizes communication skills, is based on the idea that “just one extraordinary woman can transform conflict with strength and compassion.”

Adar’s mother learned about the program and encouraged her to apply. Angelina’s mom did the same.

But Angelina’s father, who grew up watching his family fruitlessly fight to regain land they had lost after the creation of the Jewish state, told her: “You’re going to waste your summer going to this camp. You’re going to hear stories that are going to break your heart. And nothing’s going to change.”

Fifteen girls gathered at a lodge on the shores of a small lake. They included seven Jewish girls and seven Muslims. Angelina was the sole Christian.

They spent the first few days getting to know one another, taking hikes and making art.

Then the hard part began. In lengthy dialogue sessions, the girls shared their experiences of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Facilitators urged them to recall anecdotes from their own lives rather than spout opinions, and to practice listening without reacting.

As Palestinians from the West Bank described nighttime raids on their towns, the indignities of border checkpoints, Angelina felt a surge of recognition.

One of 1.6 million Arabs living in Israel, she was grateful to have never experienced violence. But she knew the sting of discrimination. She sometimes felt that people in her mostly Jewish town didn’t like her because of her roots. She commuted to a nearby Arab village to attend school.

For Adar, the criticism of Israel was destabilizing. Her grandfather came to Israel after he escaped Auschwitz, the Nazi concentration camp where the rest of his family perished. For her, Israel was more than a country. It represented salvation.

Angelina and Adar hadn’t connected immediately, but as Adar struggled through the dialogue sessions, they grew closer.

“I got really stuck on my pain,” Adar remembers. “Angelina just listened, and that was enough.”

“I was just excited to be there and listen and hug whoever needed to be hugged,” Angelina says.

Soon, the two were inseparable. Adar opened up about her parents’ recent divorce. Angelina shared her hopes for the future – to become an engineer, maybe, or an architect.After others went to sleep, they’d sneak out of bed to cook chicken nuggets or hang out in a garage that had been converted into an art studio. They made beaded friendship necklaces and listened to songs from the Fugees and Kendrick Lamar. Sometimes, they’d dive into the icy lake before sunrise.

“We didn’t have our phones,” said Angelina. “We just had each other.”

The group had formed one of the tightest bonds that organizers could remember. There were other close friendships, including one between a Jewish girl from Tel Aviv and a Palestinian from a refugee camp in the West Bank.

WHEN THEY returned home, the program continued. The girls toured Jerusalem, where a border wall cuts through some Arab neighborhoods, separating families. They heard from two mothers – an Israeli and a Palestinian – who lost sons to violence, one in a terrorist attack in Tel Aviv, the other killed by Israeli soldiers in the West Bank. The women were friends and committed to peace.

Afterward, as the girls joined in a group hug, Adar remembered thinking of the women: “If they can do it, anybody can.”

The girls liked one another so much that they implored Tomorrow’s Women to organize more events for them even after their program had ended. The group organized two other outings – a beach trip to Haifa and a dialogue session sponsored by the Canadian Embassy.

At the embassy event, a facilitator asked: What are their dreams for the future? One of the girls from the West Bank told the group that she didn’t have any. She was too consumed by stress and the struggle for survival. It was October 5, 2023. Early on October 7, Adar returned home from a party around 3 a.m. and crawled into bed.

When sirens began wailing a few hours later, she hustled to the bomb shelter in the basement of her apartment building. The sirens didn’t stop. Scrolling social media, she discovered Israel was under attack. Angelina, from her home in the North, was realizing the same thing.

She immediately messaged Adar: “Are you OK?”

She was. When terrorists in Lebanon began launching bombs at northern Israel, Adar asked Angelina the same thing. She was safe, too. But a few days in, Angelina reposted something to Instagram that angered Adar.

It was a quote from an international journalist who suggested that the October 7 attacks were the natural result of Israel’s longtime blockade on Gaza. Neither girl remembers the exact language, but it said something like: “What did you expect?”

Adar fired off a message to Angelina.

It could have turned ugly. It didn’t.

They worked things out with techniques they had learned at camp. Adar reminded herself that Angelina is an independent person, with her own feelings, and tried to really listen to her response. Angelina expressed empathy – “Nobody deserved that,” she said of the attack – and carefully explained the ideas behind her post. In the end, they agreed to disagree.

They had survived a potentially devastating hurdle. But their beloved group of friends was fraying. The problem was social media.

During camp, the girls were guided by several previous graduates of the program.

After October 7, one of them posted a video of her partner, a soldier, laughing and rifling through a woman’s intimate belongings inside a bombed-out house in Gaza. Later, one of the Palestinian graduates of the program posted a meme that appeared to express support for Adolf Hitler.

The girls’ group chat, which had been a flurry of activity, went silent.

Angelina stopped posting about the conflict, worried she would offend friends like Adar or attract unwanted attention from the government. In recent months, hundreds of Arab Israelis have been detained or interrogated in connection with things they have said online.

Angelina, who hears explosions daily from Israel’s skirmishes with terrorists on the Lebanese border, tries to avoid social media altogether. Videos of wounded children in Gaza leave her in tears. She can only glance at them briefly, then feels terrible for averting her gaze. “I feel guilty,” she says. “I’m acting like everything is fine.”

Adar is also distraught. She had friends who survived the Supernova music festival, where Hamas terrorists killed hundreds. She knows soldiers who are serving near Gaza. She’s fearful of an uptick of antisemitism around the globe.

Next year, when they graduate high school, Angelina’s and Adar’s paths will diverge.

Adar will serve in the army, as is required of nearly all Jewish Israelis.

Angelina will not. Eventually, she wants to leave.

“I don’t feel like I belong here,” she says. “I want to get my degree and go. I want to live in a peaceful country.” She’s thinking about someplace in Europe.

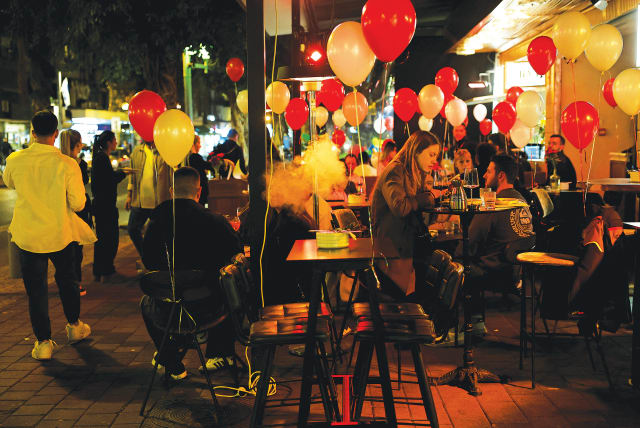

AT THE Tel Aviv café, Adar wants something sweet for brunch. Angelina has a hankering for something savory. For some reason – the mysterious logic of teenage friendship – they feel they must order the same thing. They finally settle on fruit, granola, and yogurt.

By the time the food hits the table, it’s still storming, and they are again locked in conversation.

They agree on so much. That the leaders of Hamas and Israel are to blame for the conflict. That most citizens on both sides of the Jewish-Arab divide are probably good people. That a new chart-topping Israeli trap song that calls for the destruction of Gaza is a travesty and should be taken off the Internet.

They talk about looming exams. Their favorite folk song. The time they canoed together on the lake in New Mexico. But eventually they veer into more treacherous waters.“The army is taking down Hamas,” Adar says. “We cannot have a terrorist organization around us that just wants to kill us.”

“What they did is not right,” Angelina says. “But it was expected. After 75 years under occupation –”“But it was not an occupation!”

“I’m talking about Bibi,” Angelina says, using a nickname for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. “Why is he bombing houses?”

“Because there are terrorists in the houses.”

“But there are also civilians in the houses!”

They take a beat.

“I’m not scared to talk with her,” continues Adar, resting her hand on Angelina’s.

“Yeah,” Angelina says. “We’re just talking.”

“We’re not fighting with fists,” Adar says. “You can hear something you don’t agree with and it’s fine.”

In the end, Angelina thinks her father was right about the summer camp. It didn’t change the contours of the broader conflict. But it did change her and Adar.By the time the bill comes, the rain has stopped. The girls decide to walk a few blocks to the beach.

They link arms and fall into conversation. The wind blows their hair. The sun peeks out. When people pass them, they smile. (Los Angeles Times/TNS)

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });