'The Ballad of Baruch Jamili': Forgotten story of an unsung Israeli hero

A simple, modest yet courageous fellow, Jamili was one of thousands of quiet unsung Israeli heroes who laid the foundations of Israel.

Living today in the village of Shoresh about 15 kilometers north of Jerusalem on the way to Tel Aviv, I have become reacquainted with landmarks that stand out on Highway 1. One of these landmarks is a small building that is situated on the left side of the highway going toward Tel Aviv. On the drive back to where we live, my wife and I are often caught up in traffic, and on more than one occasion the delay has enabled me to study the small beige building that appears on the passenger side. The building has a line of graffiti scribbled on the top. A few weeks ago, we found ourselves in another traffic jam.

“Quick,” I signaled to my wife, “let’s take a picture while we are stationary.” Annie was able to take two shots. She knew exactly why I had asked her to take the photograph and, fortunately, the pictures came out quite clearly. The handwritten graffiti scribbled in Hebrew reads: Baruch Jamili, Petah Tikva, Palmach 1948

The story of the building which was once a pumping station that pumped water up to Jerusalem is quite dramatic. It evokes memories of the founding of the state 75 years ago, but it also recalls a later piece of social history which I was privileged to witness.

Shlomo Artzi and the story of a once-pumping station

The event took place in 1974, when I was a youngster living in Israel. It was Yom Ha’atzmaut, less than a year after the Yom Kippur War. Israelis were still licking their wounds following the trauma of the battle that took the lives of 2,656 military personnel. In those days,

Israel had established its own version of the Eurovision Song Festival. It was called the Israel Song Festival, and it was held at Binyenei Ha’uma (the International Convention Centre). The festival was the brainchild of Kol Yisrael producer Israel Daliyot who, following a visit to Rome in 1959 when he attended the Sanremo Music Festival, persuaded the Israel Broadcasting Service to take on the idea of a song festival to be held in Israel every Yom Ha’atzmaut.

In 1974 I was living in Alon Shvut in Gush Etzion, and one of my friends, Ziona, who was a great fan of the song festival, ordered tickets for a group of us. 1974 was the last year that the song festival was staged on Yom Ha’atzmaut, and there was an air of great excitement as we arrived at the concert hall. Ziona had booked us excellent seats not too far from the stage, and we felt really fortunate to be among the live audience while the show was broadcast.

One of the competitors in the song festival was the young Israeli pop singer Shlomo Artzi. His song was called “The Ballad of Baruch Jamili,” and it told the moving story of the fighter who served with the Harel brigade, which was part of the Palmach. The Palmach was an elite Jewish strike force that fought in the two-year war that followed Israel’s creation in 1948.

The soldier’s full name was Baruch Jamili and “P.T.” stood for his hometown, Petah Tikvah, near Tel Aviv. At the end of the inscription there was an exclamation mark which seemed to express a sense of life-threatening urgency about the battle, which saw the newly created state of Israel defeat Palestinian Arabs and the armies of surrounding Arab states at the cost of 6,000 men and women, 1% of Israel’s population at the time. Jamili was stationed at Shaar Hagay, where a new museum has recently been opened.

The museum commemorates the story of the convoys that were trying to reach the besieged city of Jerusalem. Jamili’s job was to guard and protect the pumping station, while at the same time trying to ensure that the convoys that made their way through the narrow winding canyon and mountain road would not be harmed. Having recently visited the museum with a group of friends, we were struck by the desperate plight of the soldiers and those in the convoys who were fired at by snipers from above, causing terrible casualties and a great many fatalities.

Just the other day (at the time of writing this), I saw how some of the armored vehicles draped in Israeli flags were being set up along the highway to celebrate Israel’s 75th year of Independence.

After the war, the graffiti became a symbol that marked the place where many of Jamili’s comrades-in-arms fell. Since that time, many Israelis, ordinary citizens and veterans would stop to pay homage on their way to Jerusalem where the road was lined, as it is now, with some of the restored painted armored vehicles. The mystery surrounding the graffiti’s author, which did not become known until the 1970s, inspired Artzi to write “The Ballad of Baruch Jamili”: “Of the sadness of Bab el-Wad,” the song goes, using the Arabic name for the location, “only one name is left: Baruch Jamili and the Palmach.”

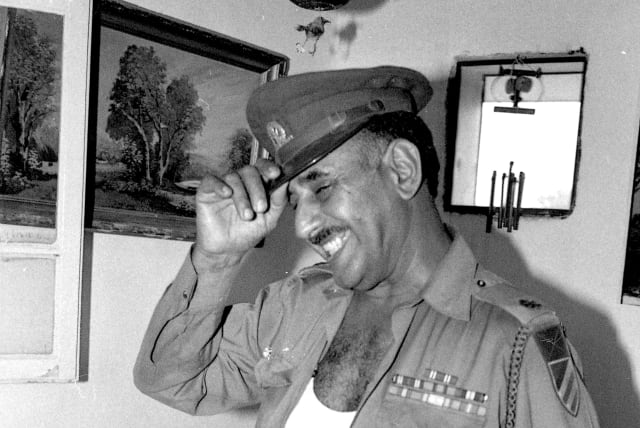

Despite not having good Hebrew back in 1974, I was able to understand the very moving words of the song. The questions posed by the song: “Who was Baruch Jamili? What did Baruch Jamili do? Where is Baruch Jamili?” were answered after the song became popular. Israelis discovered that Jamili was an Israeli of Yemenite extraction who was 25 at the time of the 1948 War of Independence.

Artzi’s performance was met with rapturous applause. The votes were counted, and he was declared the winner. I shall never forget the moment when the artist came to the front of the stage and said something like:

“In the song, we ask What happened to our hero Baruch Jamili? Well, ladies and gentlemen, I have the answer for you. He is right here with us tonight!״ With that, an older man wearing a sort of Australian bush hat stood up. He was tall and imposing, and he ascended the steps to the stage in the vast auditorium. The audience went wild, and it seemed that the shouts, whistles and applause would go on forever. I had shivers down my spine and felt tears welling up in my eyes. For years afterwards, whether I was in a cab or on a bus or driving a car, I would always look out for the little beige colored pumping station until one year, to my dismay, I noticed that the graffiti had been erased. Apparently, someone in local government somewhere had deemed it an eyesore, subsequently ordering its removal. I and many others were upset by this. I was only a tourist then and did not have the power to lobby anyone to rectify the matter. Later I read that Jamili himself had tried to fight the erasure of the graffiti that memorialized so many of his fallen comrades. Baruch Jamili died in 2004 at the age of 81. Thanks to Shlomo Artzi’s song, his story entered the collective memory of the people of Israel and assumed historic importance. So much so that on Israel’s 63rd Independence Day celebrations, the Prime Minister’s Office of the time ordered the reconstruction of the graffiti, which was carried out by Shai Farkash, a preservation specialist. The initiative was carried out by an organization called Mekorot. It’s chairman, Alex Wiznitzer, said: “Whoever does not preserve his past neglects his future.”

Cabinet secretary at the time, Tzvi Hauser, said of the restoration: “We are pleased to revive a historic icon, a short phrase that symbolizes an entire period. We salute the generation that established the state. Reconstructing the graffiti is a modest step and a gesture of gratitude to that generation.”

As Israel celebrates its 75th year of independence, the story of Baruch Jamili continues to inspire me. A simple, modest yet courageous fellow, Jamili was one of thousands of quiet unsung Israeli heroes who laid the foundations of this country. May his memory and those of his comrades be honored and preserved forever. ■