Moshe Dayan: Israel’s flawed hero

Dayan’s public and private faults do not eclipse his greatness, and maybe his shortcomings make for a more representative hero of his era and his country.

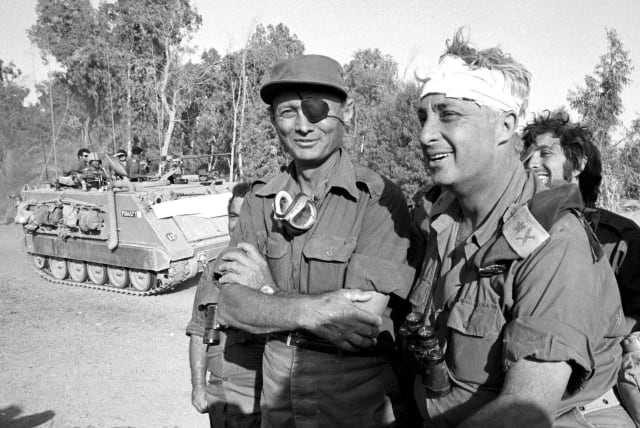

For a generation, Moshe Dayan, Israel’s legendary eye-patched general, was a national icon. Born May 20, 1915, his saga was one of rise and fall, and rise again.

On the eve of the June 1967 Six Day War, the former IDF chief of staff was embraced as a military hero and an unchallenged authority on all security matters. Seen as a savior at a time of crisis, public pressure forced a reluctant prime minister, Levi Eshkol, to appoint Dayan as defense minister, a decision that forever associated Dayan with Israel’s ensuing victory.

But the October 1973 Yom Kippur War brought about the collapse of Dayan’s previously unrivaled public persona. From “Mr. Security,” he became almost the devil incarnate, whom bereaved families held responsible for the deaths of their loved ones. Dayan left the Defense Ministry in shame, with many assuming his time in national leadership was over.

He nonetheless made a comeback. In May 1977, newly elected prime minister Menachem Begin asked Dayan to serve as foreign minister. Begin thought Dayan’s international prestige could allay fears abroad about Israel’s first Likud government. But Dayan was never a fig leaf; he played a pivotal role in the negotiations with Egypt that led to the historic March 1979 peace treaty.

At the height of his fame, Dayan was adored in Israel and across the Diaspora. His picture was proudly hung in many a Jewish home – there were even Moshe Dayan calendars and ashtrays.

BORN INTO Labor Zionist aristocracy, Dayan was the son of Second Aliyah pioneers – Israel’s “Mayflower.” He was the first child born in Deganya, the first kibbutz, and grew up in Nahalal, the first moshav.

There a narrative was established about a young man who worked the soil by day and guarded the fields by night. It was a natural progression to the pre-state paramilitary Hagana and then, after Israel’s founding, to the IDF.

Epitomizing the tough and plucky Sabra, Dayan demonstrated his bravery in June 1941, fighting alongside the Australians against the Vichy French in Lebanon – where he lost his eye in combat. His boldness in battle was on display again in 1948 during Israel’s War of Independence, when he commanded a commando battalion.

Like many in the newborn state, Dayan was an activist on defense issues. As a general in the early 1950s, he championed the IDF’s controversial cross-border reprisal raids against locations from which terrorist attacks were launched.

Later, as chief of staff, Dayan would be the exponent, planner and executioner of the October 1956 Sinai Campaign in which Israel attacked Egypt and occupied Sinai and Gaza (in collusion with Britain and France). And when prime minister David Ben-Gurion acquiesced to American demands to pull back, Dayan let it be known that he opposed the withdrawal.

Dayan's respect, understanding and stances

Furthermore, as defense minister following the 1967 victory that saw Israel more than double the territory under its control, Dayan said that if the Arabs wanted land back, they could reach him by telephone, but until receiving such a call, Israel would sit tight and build settlements. He even declared his preference for a permanent Israeli presence at Sharm el-Sheikh in Sinai over peace with Egypt.

Yet, in contrast to many Israelis, Dayan showed an understanding of, and respect for, Arab hostility. In May 1956, as chief of staff, he eulogized Nahal Oz kibbutznik Roi Rutenberg, who was killed by Palestinian fedayeen:

“Let us not condemn the murderers. What do we know of their fierce hatred for us? For eight years they have been living in the refugee camps of Gaza, while right before their eyes we have been turning the land and the villages, in which they and their forefathers lived, into our land.

“We should demand his (Roi’s) blood not from the Arabs of Gaza, but of ourselves… We are a generation of settlers, and without a helmet or a gun barrel we shall not be able to plant a tree or build a house. Let us not be afraid to see the enmity that consumes the lives of hundreds of thousands of Arabs around us… This is the fate of our generation. The only choice we have is to be armed, strong and resolute.”

Perhaps the “armed, strong and resolute” mindset of Golda Meir’s government (1969-74) contributed to the diplomatic stagnation that led to the Yom Kippur War.

But in the spring of 1971, Dayan broke with Jerusalem’s consensus that only the signing of a peace treaty with Egypt would have Israel pull back in Sinai. He suggested that in return for non-belligerency, Israel would conduct a partial disengagement along the Suez Canal – “less for less.”

Egyptian president Anwar Sadat also expressed an openness to a limited Israeli withdrawal as a first step toward a comprehensive peace that would see a return to the pre-1967 lines.

DAYAN UNDOUBTEDLY bears much responsibility for the failures of the 1973 war – including not fighting hard enough in the cabinet for his own proposal that contained the possibility of averting the conflict in the first place.

After stepping down from the Defense Ministry in June 1974, Dayan spent three years on the back benches. Then, to the great chagrin of his Labor Party colleagues, he crossed the floor to be Begin’s chief diplomat. But if Labor saw Dayan as selling out to the intransigent Right, he was to surprise.

At the September 1978 Camp David peace summit, Dayan became president Jimmy Carter’s go-to person whenever a problem in the talks seemed insurmountable. According to the American negotiators, Dayan had an acute awareness of Egypt’s real positions, together with the uncanny ability to produce a compromise formula acceptable to the ideological Begin.

After succeeding in helping forge Israel’s first-ever peace agreement with an Arab country, Dayan fell out with his prime minister. He felt Begin was not serious about the talks on Palestinian autonomy and in October 1979 resigned in protest.

In the June 1981 Knesset elections, Dayan ran as an independent centrist. Receiving a disappointing two seats, his political career was ending just as cancer was destroying his physical being. He died on October 16, 1981, aged 66.

During his life, Dayan drew criticism for his personal behavior: The stolen archaeological artifacts, multiple liaisons with women, and tortured ties with his three children.

But Dayan’s public and private faults do not eclipse his greatness, and maybe his shortcomings make for a more representative hero of his era and his country.

The writer, formerly an adviser to the prime minister, is chair of the Abba Eban Institute for Diplomacy at Reichman University. Connect with him on LinkedIn, @Ambassador Mark Regev.

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });