Murder and rape in the dunes of pre-state Israel: The story of a hike turned horror

They were friends and perhaps wanted to become lovers. They also loved the Land of Israel and set out to walk through it. Tragically, their walk was horrifyingly interrupted.

It was to be a two- or three-day hike from Tel Aviv to Herzliya. But they never finished their trek.

They were friends and perhaps wanted to become lovers. They also loved the Land of Israel and set out to walk through it. Tragically, their walk was horrifyingly interrupted.

Yochanan Stahl was born in 1908 in Germany and was orphaned from his mother in 1925. His high school education was in an agricultural school at Ladenburg, east of Mannheim, and he joined a socialist-Zionist youth movement. He applied and received an immigration certificate for Mandate Palestine and arrived in late 1929, despite family opposition and leaving behind a girlfriend, Anna.

Stahl first worked at Kibbutz Beit Zera, and then Kibbutz Sarid in the Jezreel Valley but, in December 1930 moved on to Givat Brenner and worked in the orange groves near Rehovot. A relative described him as not that tall, curly haired, with blue eyes.

Celia/Sarah Zohar (Zonnenshein) was born in Chodorów, southeast of Lviv – then Galicia – in 1902. At the outbreak of World War I, the family moved to Vienna. Her brother was Dr. Zvi Zohar, a founder of Hashomer Hatzair, the Tarbut Hebrew school system, and Shomriya, the educational institution at Mishmar Ha’emek. She also joined a Zionist youth movement and studied pediatric nursing.

Zohar made aliyah in 1928, first working at the Ben Shemen Youth Village and then moving to Sarid, just west of Migdal Ha’emek and south of Nahalal. Prof. Ezra Sohar, her nephew, recalled that Celia and Yochanan met at Sarid.

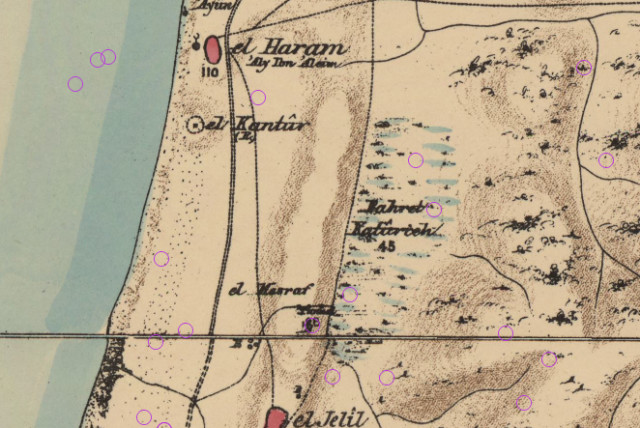

While Celia was on a family visit to Poland, Yochanan wrote to her that he had found a spot some “30 meters high; to my right Sidna-Ali, to my left Jelil village [today, south of the Dan Accadia Hotel], behind me Herzliya and before me – the sea. I promise that when you return, we’ll hike to this place.”

A hike that turned into a murder

On Sunday morning, June 28, 1931, the 13th of Tammuz, Celia packed a small suitcase, including a swimsuit, and left Ben Shemen for Tel Aviv. Yochanan, after receiving a three-day leave from work, set out from Givat Brenner to meet her. He took his grafting blade with him. Their intention was to go on foot to where a Kibbutz Me’uchad pioneer unit was camped at Herzliya III.

They met up at Tel Aviv’s Herzliya High School at the corner of Herzl and Ahad Ha’am streets after Celia had met a friend and borrowed some clothes. They wrapped up sandwiches in a newspaper and took a bus to the last stop at the Yarkon River.

Arriving at around 10 a.m., they crossed the river in Natan Cohen’s boat. They turned left and walked west toward the sea and then began hiking northward.

And then they disappeared.

THE FIRST notices in the newspapers asking for information surrounding their disappearance appeared some two weeks later. A reward of 20 Palestinian pounds (PP) was offered, an insignificant amount. Nothing resulted.

The Yagur murders in April that year were in people’s minds [on April 11, 1931, three members of Kibbutz Yagur were killed by members of a cell of the Black Hand, and concern for the pair’s lives was palpable in the additional multiple pleas for information throughout the summer. Several searches were conducted, covering the area between Tel Aviv and Hadera. Foreign consulates intervened. It was only on the Thursday night of November 12-13 that the bodies were found.

The case was cracked by Avraham Druian with assistance from Avraham Shapira, two shomrim [guards] acting independently of the police, who managed, with financial inducement, to convince Bedouin chieftain Ali-Kassem Abd-Al Kadar to have his tribesmen obtain evidence and proof. Ali-Kassem, from Taybeh, lived near Tel Litvinsky, today’s Tel Hashomer. By September, with the failure of the police to succeed, Druian enlisted 10 Arabs to be his eyes and ears, paying them the sum of PP 5 each. The suspicion fell on Bedouins near Jelil, after a young Arab shepherd found bits of garments and reported the find to Ali Kassem.

Riding on horseback, Druian searched the area close to Sidna-Ali and found a piece of newspaper dated June 28.

On November 10, Druian met Ali-Kassem, who needed PP 300 to gift the mayor of Tulkarm, to obtain his permission to marry his daughter, whom Ali-Kassem desired. The meeting took place at Miska village (just east of Ramat HaKovesh), and Druian learned that the murderers were at the encampment of the Al-Quran Bedouin.

One of the Bedouin had bragged that his blade had recently “tasted the blood of a non-believer,” a remark passed on to Ali-Kassem. The police raid took place two days later, on Thursday night, November 12, and into the next day. Arrests were made and confessions obtained.

The site of the murders was near Tel Michal (Makmish), a sandstone ridge south of Herzliya, 6.5 km. north of the Yarkon estuary and 4 km. south of Arsuf or farther south, at Tell Rekeit, west of the Azorei Hen apartments. The bodies were buried, separately, in an area that had served as a line of defense dugouts by the Turkish army during World War I. Two of the suspects were forced to lead the searchers to the place where the bodies were supposed to be buried, and then a third led the police to the same place.

The actual search over a large area took nearly three hours until one of the suspects came upon the body of Stahl. After a further search, Zohar’s body was found slightly to the south (near today’s Cinema City Glilot). They were buried in Tel Aviv’s Trumpeldor Cemetery that Friday at 3 p.m.

Further interrogations revealed that the couple had met an Arab mounted on a camel, and after a short exchange he left them and they continued northward. Then another group of camel-mounted Arabs overtook them, returning from transporting watermelons to Jaffa. They gave the two a short ride on the camels. Upon approaching the Arab-Al-Quran encampment, the couple alighted and set off for the sea.

The camel riders met two shepherds and, together, they planned to attack the couple. Stahl was approached from behind and stabbed repeatedly on his left side with a watermelon knife. They chased the fleeing Zohar, struck her on the head with a stone, and then all five gang-raped her. They then stabbed her to death. Post-mortem forensics found that Stahl had been buried while still alive. The killers removed Zohar’s ring and took Stahl’s grafting blade.

THOSE ARRESTED included Rashid Mussa Abu Suliman, Hanni Ibn-Salib Abu Suliman, Said Mustafa Ahmad, and Ahmad Ibn-Awad Abu-Hadib from the Al-Quran, Al-Malalha, and Suarki tribes. Present at the arrest were Oved Ben-Ami and the brothers, Gad and Moshes Machnes, all of the Bnei Binyamin Society who provided the financial inducement.

Only two reached trial, as reliable provable evidence was lacking. Rashid Abu Suliman, 20, was found guilty of murder and sentenced to 15 years imprisonment. The second defendant, 17-year-old Hanni Abu Suliman, his cousin, was released. Paradoxically, the press, both Jewish and Arab, expressed satisfaction that the murders were not politically motivated. Nevertheless, two members of the newly formed Irgun Bet, the Revisionist breakaway group from the Hagana, requested permission for a revenge reprisal action; however, permission was denied.

In the end, the Stahl and Zohar families never spoke to each other again. Stahl’s parents were gassed at Auschwitz, but his two brothers survived and reached Israel. Druian named one of his daughters Zohar. He died in 1982. Poet Uriel Halperin (later, Yochanan Ratosh) issued a 43-page poem which sold 3,000 copies – phenomenal in those days.

Ali-Kassem was suspected of treachery by Isser Be’eri of the Hagana’s Intelligence Service and executed on November 16, 1948. Be’eri was discharged as punishment. In 1933, Sima Arlosoroff referenced the Stahl-Zohar case in her testimony regarding the murder of her husband, Chaim, regarding the fear she experienced when accosted on the north Tel Aviv stretch of beach when her husband was shot and killed in June that year.

The plaque affixed to the graves of Stahl and Zohar reads: “To the memory of innocent wayfarers/ Who were ambushed by man’s evil./ O how the pure and decent were eliminated.” ■

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });