Yom Kippur War Blues: A soldier reflects on feeling abandoned

Artist Avner Moriah’s army service during the Yom Kippur War has colored his artwork for decades.

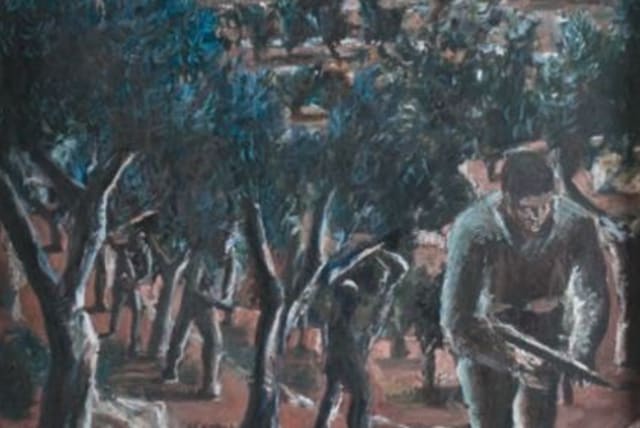

It’s 3 a.m., and artist Avner Moriah is busy in his home studio, mixing ruby-red and lush-green watercolors to illuminate yet another biblical theme. As he painstakingly dilutes his paints, he is mindful of his life-size oil painting on his wall of Israeli soldiers running into battle – an ever-present reminder of his own Yom Kippur War service. The painting is part muse, part daily salute to his fellow soldiers.

For this secular Israeli, creating a visual lexicon of Jewish texts and themes is more than just a daily routine. It’s Moriah’s personal expression of spirituality that gives meaning to having survived the harrowing war. The results, he says, are his gift to the Jewish people.

That legacy spans a Jewish holiday series, an acclaimed illuminated Torah, a breathtaking Haggadah, bucolic landscape portraits of Israel, and two Guinness World Records for his whopping 34-meter Ganze Megillah Scroll of Esther (as tall as an 11-story building) – to name but a few of his monumental pieces.

The artworks that emanate from his paintbrush express his myriad emotions and his connection to the Jewish people, exemplified by his roundels depicting the Jewish holidays. The circular format is symbolic of his own evolving relationship with Judaism, Israel, and traditional Jewish texts.

His Yom Kippur roundel, in particular, synthesizes his personal history with biblical verses. Created in the early 2000s as part of his 12-part Jewish holiday series, it expresses the abandonment and betrayal he felt by politicians during that fateful Yom Kippur of 1973.

The inner ring of his Yom Kippur piece depicts the central motif of the holiday service. As the biblical verses in Leviticus Chapter 16 relate, a goat is chosen, and the high priest places the sins of the Israelites on it. Then the goat is cast into the desert.

“My childhood home is in the Abu Tor neighborhood of Jerusalem. The desert is literally next door, where in biblical times they threw the goat over a cliff. Those of us who served in the Yom Kippur War felt like we were sacrificed, too,” says Moriah, 69, an IDF cadet when the war broke out.

“The political leadership just threw us into battle and sacrificed our youth forever. We were the modern-day version of those biblical verses. We were the politicians’ scapegoats,” says Moriah, who was stationed in Sinai when the war began.

Political scapegoats: A Yom Kippur War story

In 1973, he was at the end of his officers’ training course. He recalls that in the weeks leading up to the October war, he and his fellow cadets were sent to the Golan Heights as part of their training. There, they could see an unusual buildup of Syrian troops not far from the border.

“Everyone said that they didn’t know what it portended. I said, ‘Maybe they are preparing for war.’ They all laughed at me. It shows how we lived in La-La Land. Now you see in the media that even then there were people who were questioning the Syrians’ intentions.

“I was 20 years old when the war started. I remember thinking to myself that it would be a funny age to die.”

WHEN MORIAH finished his military service, he enrolled in the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, and later earned a master of fine arts degree at Yale University. Early in his career, he was recognized for his evocative landscapes of Israel as he journeyed throughout the country, with his paints, easel, sun hat, and gun (just in case) in tow. Many of these paintings are now part of prestigious private and public collections, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

In 1980, he set off to New York, where he funneled his feelings about the war into his artwork. There, he spent eight years working intensively on his dramatic 100-painting series depicting various scenes of soldiers in combat. These were not easy times. “I was still in a state of trauma,” he reflects, half a century after the war. “I would wake up sweating. I definitely had PTSD.”

But the sojourn there with his wife and children proved to be life-changing, exposing him to the city’s vibrant Jewish community. As he accompanied new friends and patrons to the synagogue and shared holiday meals with them, he gained insights into Jewish life and traditional texts.

Among his patrons was Gershon Kekst, then chairman of the board of the Jewish Theological Seminary, who collected many of Moriah’s landscapes. “He would always tell me, ‘Boiychekel, you should start doing something for the Jewish people. What about the Jewish texts?’” Kekst then commissioned Moriah to create panels on The Gathering at Mount Sinai for JTS, which was completed in 1999. The artwork was hung at the august institution for many years.

The commission marked the genesis of Moriah’s foray into illuminating Jewish texts and themes. These artistic projects had him circling back to his wartime buddy Rabbi Shlomo Fox, with whom he shared a room during their time in the officers’ training course. Realizing that there were large gaps in his Jewish knowledge, Moriah spent many hours studying with Fox, learning how biblical texts were understood in the Midrash and Talmud and interwoven into traditional Jewish rituals.

It turned out to be an eye-opening education, particularly reflected in his roundel of Yom Kippur. “As an Israeli, I am very familiar with the Book of Jonah,” Moriah says, “but how would I have known that it is read on Yom Kippur?”

For Fox, a seasoned Jewish educator, teaching Moriah was an education for him as well. Fox marveled during their sessions, as the artist literally tried to “see” how he could express the texts. “When we studied a midrash, he would visualize the texts in pictures,” Fox recalls. “It was fascinating.”

The elegant artwork of Moriah’s Yom Kippur roundel features vibrant colors, as well as stick figures to depict humans and animals, a nod to drawings that characterize images from the Early Bronze Age. Related biblical verses, with elegant lettering by master calligrapher Izzy Pludwinski, surround the illuminated images. Moriah’s depiction of Jonah’s odyssey, framing the outer layer of the roundel, has a modern, contemporary vibe, unmistakably relaying the dramatic story of the reluctant prophet.

“I am much more knowledgeable now than I was then,” Moriah reflects. Though resolutely secular, he stresses, “I am very connected to my Jewish historical heritage, the Land of Israel that I painted so intensely, and to the Jewish holidays.

“All my grandparents were ultra-Orthodox Jews from Europe who fled the tyranny there. My mother’s parents left religious life and became ardent Zionists. I knew about the Jewish holidays, but that’s about it,” Moriah recalls. “I’ve come full circle in my relationship with Judaism and traditional Jewish sources, though I still hold my secular views. I love my people and our traditions.”

MORIAH’S INSATIABLE desire to create a visual lexicon of biblical texts sparked his decision in 2006 to undertake the mammoth project of illuminating the entire Pentateuch. “I was determined to contribute a unique visual interpretation of these ancient texts for all who deeply care about the written word and painted image,” he says.

He spent much time meticulously studying the Torah with biblical scholar Prof. Yair Zakovitch of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who notes: “We can say, paraphrasing a verse from the story of the Giving of the Torah, that Moriah sees the voices and translates them into color and line.

“He often creates images that move back and forth in time, referencing central motifs and comparing and contrasting them in an effort to clarify his – and our – understanding. The freshness and originality of Moriah’s images derive from the deep connections he draws between the biblical text and the Land of Israel (whose vistas he so often captures on canvas) and its particular light.”

Moriah recalls a subway ride in New York City as he grasped the rolls of archival paper he had just purchased for his Illuminated Book of Genesis. “I marveled at the simple blank paper that would soon be imbued with God’s spirit, and I knew I was ready to begin my journey.”

It took him 15 years to finish all five books. Major institutions – such as the Library of Congress, the New York Public Library, Yale and Harvard libraries, Oxford University Library and the Bibliothèque nationale de France – have included his magnum opus in their prestigious collections.

In 2012, he presented his Illuminated Book of Genesis to Pope Benedict in a special audience at the Vatican. And in 2017 he again journeyed to Rome to present his Illuminated Book of Exodus to Pope Francis. Both books are now part of the Vatican Library. In July 2022, he traveled to Spain, where his Genesis volume was given to King Felipe VI.

The trajectory of his success is not lost on Moriah, who has struggled with dyslexia throughout his life. He recalls a scene when his older brother was given an illustrated children’s Bible at a family Seder. “I cried so hard because that was the gift I wanted. Looking back, it’s all so ironic that my Illuminated Torah is now part of world-renowned libraries,” he chuckles.

It’s now 4 a.m. and Moriah is oblivious to the inky-black sky of the night that frames his window. He’s focused on mixing the right shade of orange to apply to the biblical scene he is currently illuminating. For Moriah, the act of creation simply can’t wait for the dawn of a new day. ■

To view more of Moriah’s extensive artworks, visit www.avnermoriahprints.com.

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });