The history of war idioms and expressions

Let’s take a look at some idioms related to battle and see what they mean and how they originated.

In this fight to the finish that Israel is waging, there are no unsung heroes. To every valiant soldier in the battle arena, and every altruistic individual on the home front aiding in the war effort, we sing their praises.

The idea that heroes should be celebrated in song goes back thousands of years. It is believed that the origin of the term “unsung hero” dates back to the Greek poet Pindar (518-447 BCE), who celebrated the athletes in the Panhellenic festivals in a series of odes. In his book The Isthmian Odes, Pindar wrote: “Unsung, the noblest deed will die.”

There are many phrases such as “to sing the praises” in the form of infinitives that have stood the test of time. Let’s take a look at some of those related to battle and see what they mean and how they originated.

The history of wartime expressions and idioms

“To bite the bullet” means to force yourself to do something unpleasant or difficult, or to be brave in a difficult situation. The phrase was first recorded by Rudyard Kipling in his 1891 novel The Light that Failed. During the Civil War, soldiers on both sides of the battle allegedly bit down on a bullet to keep from making a sound while undergoing a painful medical procedure on the battlefield.

In the realm of guns, “to shoot from the hip” means to react suddenly or without careful consideration of one’s words or actions. The term refers to gunmen who fired their pistols or rifles from the hip area, without really aiming the firearm at someone. That did not happen often because those who shot from the hip were likely to miss, unless their target was up close. The fast-draw from the hip was the real secret. The farther you pull the gun from the hip, the more time it takes. If you want to be a fast-draw, you draw and then fire from the hip.

In that vein, “to be a straight shooter” means to be forthright and upstanding in behavior. The term may also apply to a person who is blunt, sometimes to the point of being harsh or offensive. Essentially, it alludes to a person who speaks in an honest and direct way, like the straight path of a bullet shot from a gun. The expression has been in American slang since the latter half of the 1900s. Originally, it referred to a gun in a carnival target shooting game that did not have its sights misaligned.

While we are in the line of fire, “to stick to your guns” means to refuse to compromise or change your mind; to maintain your own opinion about something, even though other people are trying to tell you that you are wrong. The idiom, dating from 1841, meant to not flinch under fire. “Stick to your guns” was a command given to sailors manning the guns on military boats. They were to stay at their posts even when the boat was being attacked by enemies.

Remaining on the bounding main, the expression “Tell it to the Marines” means “I don’t believe you.” The term was generally used in response to a story that seemed far-fetched. The idiom originally made reference to Britain’s Royal Marines, connoting that the person addressed was not to be believed. The full phrase was “Tell it to the Marines because the sailors won’t believe you.”

An expression that made its way into the seafaring arena is “to be armed to the teeth.” Originally, in the 14th century “to be armed to the teeth” meant to be well equipped, as knights often wore head-to-foot armor. Then, in the 1600s, the term was used in Port Royal, Jamaica, when pirates were constantly looking for ships to loot. As their guns were very primitive, they could shoot only once before a long reloading process. Consequently, they needed to carry a gun in each hand, and also perhaps in each pocket. For extra power, they would also hold a knife between their teeth. So to be ‘’armed to the teeth’’ meant to carry the maximum number of weapons possible. The idiom gained currency in the mid-1800s, applied to wielding a great amount of weaponry or other military equipment.

While in warfare it may have been de rigueur to overtly display one’s military might, the custom “to shake hands” emanated in times of peace. To clasp a person’s hand in greeting, congratulation, or agreement was a way to communicate goodwill. Extending an empty hand was a direct way of saying, “I’m not holding a weapon, so I’m not going to hurt you.”

The practice, which first unfolded in Rome, was more of a forearm grab to make sure that the person being greeted wasn’t carrying a knife in his sleeve. The act of physically shaking the hand, not just extending it, is believed to have originated in medieval Europe, when knights would take someone’s hand and shake it so that any loosely hidden weapons would fall to the ground.

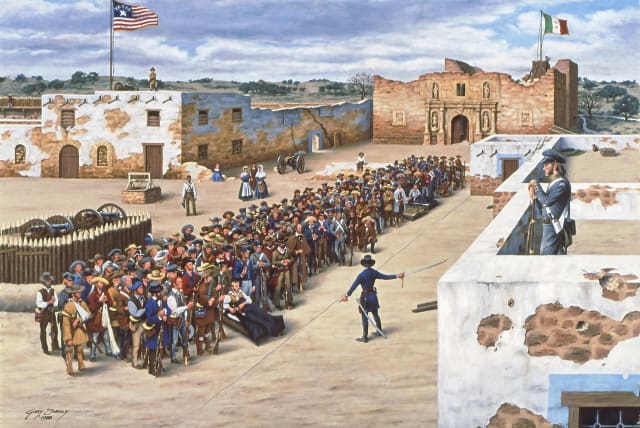

And speaking of the ground, “to draw a line in the sand” means to designate a point beyond which one will not go; to set a limit to what one will do or accept. In the US, the term is commonly accepted as a reference to the action of William B. Travis. In 1836, while commanding the defenders of the Alamo against Mexican troops and contemplating a demand for surrender, Travis drew a line in the sand with his battle sword and asked those willing to remain and defend the Alamo to their deaths to step across it, understanding that their decision would be irreversible. Most did – and it was. Between 182 and 257 Texans died valiantly defending the fortress in San Antonio, among them Travis, Davy Crockett, and Jim Bowie.

However, “to bury the hatchet” in the ground means to make peace; to end a quarrel or conflict and become friendly. The phrase is an allusion to the figurative or literal practice of putting away the tomahawk at the cessation of hostilities among or by Native Americans in the Eastern United States, specifically during the formation of the Iroquois Confederacy. As a custom among the Iroquois, weapons were buried or cached in times of peace.

Another symbol of the desire to make peace is “to raise the white flag.” This indicates one’s surrender, defeat, or submission. The white flag is waved to show that one accepts defeat or does not intend to attack. The raising of a white flag is a well-known symbol of truce and surrender. A white flag or a piece of white cloth hoisted to signify surrender or request a truce. The first mention of the use of white flags to surrender is made during the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 CE). In the Roman Empire, historian Cornelius Tacitus mentions a white flag of surrender 109 CE. Before that time, Roman armies would surrender by holding their shields above their heads. Most historians believe that blank banners first caught on because they were easy to distinguish in the heat of battle. Since white cloth was common in the ancient world, it may have also been a case of troops improvising with the materials they had on hand. Medieval heralds carried white wands and standards to distinguish themselves from combatants, and Civil War soldiers waved white flags of truce before collecting their wounded. The various meanings of the white flag were later codified in the Hague and Geneva Conventions of the 19th and 20th centuries. Those treaties also forbid armies from using the white flag to feign a surrender and then ambush enemy troops.

After winning a battle, the victor might be prone to get on his high horse about it. “To get on your high horse” means to behave in an arrogant, superior, or pompous manner. The term “high horse” dates back to the 14th century, when horses were the primary mode of transportation. Military leaders and knights rode taller horses as a sign of rank, authority, and the practical advantage of being elevated above foot soldiers. Metaphorically, the phrase evolved during the 18th century when individuals on “high horses” were regarded as looking down on others from a position of arrogance.

Be that as it may, in a conflict both sides must pass muster in order to be fit for battle. “To pass muster” means to meet a required standard. Deriving from the military, the term means to pass inspection. If you join the military, you muster in; and when you leave, you muster out. “Muster” also refers to lining up for a formal military inspection, the goal of which is to pass muster. So “to pass muster” originally meant to undergo a military review without censure.

In this grueling battle in which Israel is embroiled, the IDF has more than passed muster. It is a valiant, righteous force that is dedicated to preserving this nation for all it’s worth. It is a war we must win. ■

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });