‘I am not a Zionist’: How it really was

Until just a few years ago, visiting Americans would still ask me, “Do you like living here?”

The year: 1947.

The place: the back row of a red-and-cream TTC (Toronto Transit Commission) streetcar. A by-chance meeting between an 18-year-old former Hebrew school mate, and the 16-year-old (passing for 18) me, then known as Syd Applebaum.

My streetcar neighbor made his statement a few times, louder than I would have preferred in that public place: “I’m not a Ziontist (yes, the original extra “t” was just as he pronounced it) but I would go fight in Palestine. I would go fight there, even if I’m not a Ziontist.” I squirmed in my seat. What if we were overheard and reported... The secret would be out!

Neither of us went to fight in the War of Independence. I made it to Israel in December 1952. He never came here as far as I know.

But what triggered that bizarre and dangerous pronouncement in such an ill-chosen place?

Why dangerous? What we were doing was probably illegal and had to be clandestine, “secret.” My loud and ignorant “friend” had seen me at an under-the-wraps gathering of about 200 young Toronto Jews in a Hebrew school auditorium. It was a recruitment meeting for the Hagana. Invitation by word-of-mouth. That explains the quotation marks about “secret.” Two-hundred secret-keepers??

The Background: the knowledge that Hitler had killed all or most of our families in Poland and its Eastern and Central European neighboring states. Furthermore, the Yishuv in the Land of Israel, a bare 650,000, was fighting for its life against local Arab militia and village gangs, while five Arab armies were poised to invade British Mandatory Palestine the moment the Union Jack would descend the flagpole.

The secret-sharing attendees on that 1947 Toronto day included a cluster of “Ziontist” youth movement seniors, some Hebrew school graduates, and a number of former RCAF (Royal Canadian Air Force) and Army veterans. Also included were a smattering of our local tough guys – ”pool hall types” and “Spadina Avenue bums.”

I recognized one Air Force vet, Al Spiegel, whose sister Hannah I was dating and later married. In the days that followed I met Al numerous times while courting Hannah at their Euclid Avenue home. We purposely avoided crossing glances and never referred to where we had been that day. Al did get to Palestine and fought in the newly-minted Givati infantry brigade, and later manned an air control tower at Tel Nof.

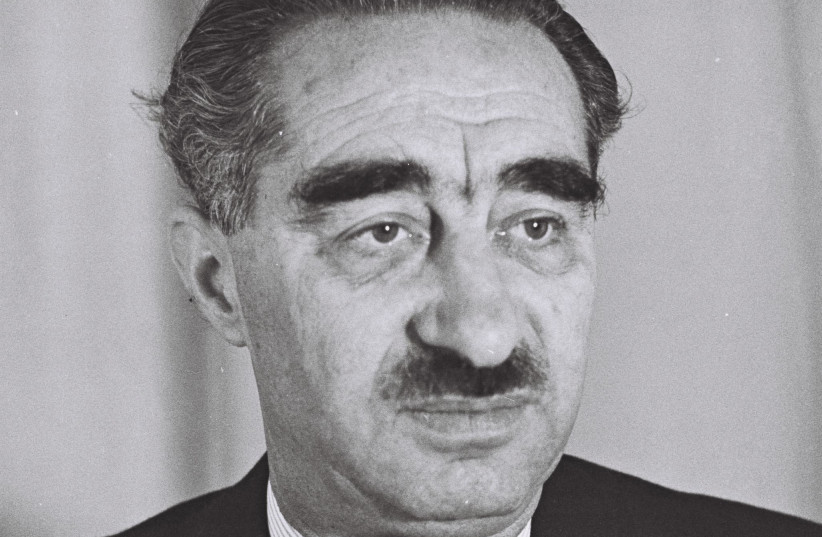

To return to the recruitment meeting in 1947. The speaker in the auditorium of the Brunswick Avenue Talmud Torah was Maj. Abraham Friedgut. I do not recall the content of his speech, but it could only be the obvious: the need for free immigration of Jews to Palestine that only a State could guarantee.

There were the hundreds of thousands of so-called Displaced Persons, mainly Jews who knew that only Palestine, or for some, the New World, would offer them a free life. They knew that violent antisemitism already had taken Jewish lives in Poland and other blood-soaked countries in Eastern and Central Europe after the collapse of Nazism. Some might even be our own flesh and blood. We would also have spoken of the Arab armies ready to invade and join the Palestinian Arab militia and irregulars, and whose leaders spoke of throwing all the Jews into the sea. A second Holocaust.

At the end of the meeting, questionnaires were passed around seeking information about previous military service, experience with firearms, etc. One question stayed in my mind across the decades: “Can you ride a motorcycle?”

We were also advised to obtain a passport. I wrote away to Ottawa (the capital of Canada, in case that is news to the reader) and in due course received a dark blue passport, endorsed to “All Countries.” As such I would be able to travel to Beirut and be smuggled into Palestine.

A footnote to the Friedgut saga. Maj. Friedgut was a leader of the Canadian Zionist Organization. He had served in the Jewish Battalion of the 39th Royal Fusiliers in World War I, which was raised from American and Canadian volunteers. His fellow battalion members included David Ben-Gurion and Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, then in exile in Brooklyn from Turkish-controlled Palestine, and Dov Yosef (Bernard Joseph) of Montreal. With statehood, Ben-Gurion became prime minister, Ben-Zvi the second president of Israel, and Dov Yosef military governor of Jerusalem and then minister of rationing and supply.

In the Second World War, Abraham Friedgut, who had returned to Canada, joined the Canadian Army and reached the rank of major. In 1948 he and Mrs. Friedgut settled in Jerusalem. My path crossed the major’s son, Theodore (Ted), decades ago when he was a professor of Russian and Slavic Studies at Hebrew University, specializing in the Soviet Union, and I served as vice-provost of the Rothberg International School.

Back again to 1947. My blue passport arrived at our home on Yarmouth Gardens Avenue, and was intercepted by my parents. Then followed a rather fraught discussion. I do not think there were tears on my mother’s part. Their argument was: “You are too young now. Finish your education and then go to Israel.” I realized I was not ready for Israel yet.

This sense was backed by the only Israeli shaliach (emissary) then in Toronto, a member of Hashomer Hatzair, but whose authority was unchallenged since he was from Israel! “At your age, better to stay here and keep the movement going.”

A few months later, I was asked to go to Los Angeles to strengthen our three branches there (Beverly-Fairfax, West Adams and Boyle Heights). By then, Hashomer Hadati had merged into Bnei Akiva, which then still had a social agenda.

Our days in LA were exhilarating. The movement had “sent” me to LA with a one-way train ticket and the promise of a job as a Hebrew school teacher, a job that never materialized. The long train ride – three nights and two days – found me new friends, in the Alice Finkelstein-Zohar family, with whom I stayed until Hannah flew out to join me. She paid her own airfare. Though we worked full time, we still devoted weekends and summer vacations to the movement.

Hannah was a trained bookkeeper and immediately found work at the Jewish fundraising arm of the City of Hope, begun as a clean-air retreat and hospital for the poor Jewish east-coast tubercular slum-dwellers who worked in the sweatshops of the garment trade and shoe factories.

I later found employment there with its Yiddish-speaking Central Jewish Committee, and a year later I became director of Publicity and Public Relations for the fundraising campaign for the Israel Histadrut. This eased my way into The Jerusalem Post, where I was hired by its founding editor, Gershon Agron, in July 1952, after working about six months in a religious kibbutz. (We had arrived in Israel on December 28, 1952)

Hannah stayed on in the kibbutz another month. She immediately found work at the Jewish Agency and with two breadwinners, life in Jerusalem became viable. I never looked back. Hannah, from whom I parted in 1980, always missed her multiple siblings terribly.

So, dear reader, this is being written to share with you the feel of that era, beginning almost 75 years ago.

I now mark the beginning of my 70th year in Israel, made all the more positive by Henrietta, my wife of nigh on 40 years, and the immense devotion and love of our offspring, their children and grandchildren.

Until just a few years ago, visiting Americans would still ask me, “Do you like living here?” Well friends, don’t ask this “Ziontist!” Ask one of the second or third generations of the older ones of the fourth generation in Israel. They might just tell you that we are all “Ziontists.”

The writer dedicates this column to Prof. Joshua Levinson, co-editor of the recently published Jews and Journeys: Travel and the Performance of Jewish identity, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). A former chairman of the Department of Hebrew Literature at the Hebrew University. Levinson is married to the writer’s daughter Shoshanah.

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });