Does Psalm 91 contain a remedy for COVID-19?

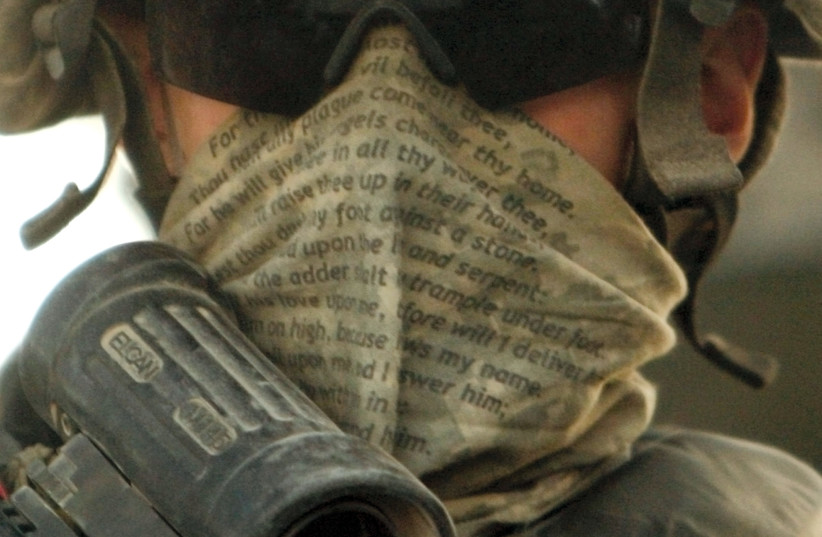

The Jewish response to the coronavirus pandemic was largely traditional: fasting and repentance, prayer and Psalms, especially Psalm 91 (Yoshev B’Seter).

Religion and medicine have a long intertwined history. The Bible has much to say about illness, its origins and ideology. Sanctuary priests often served as public health officials. Suffering was generally regarded as punishment for sin. The post-biblical age enshrines folk remedies of many kinds.

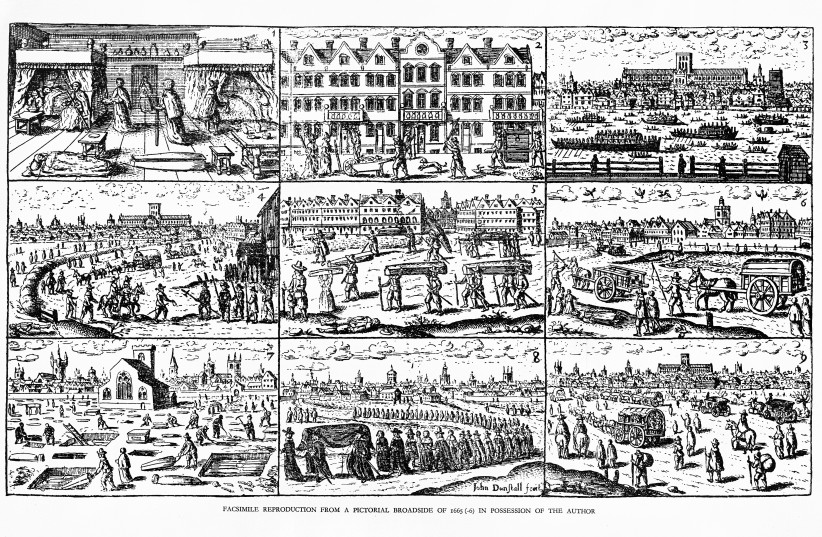

In the Middle Ages, many rabbis were doctors and looked for ways to overcome old ideas. Maimonides was an advanced medical thinker for his time and the writer of many medical treatises. His comprehensive attitude to body and soul was highly progressive. In the general population, superstitions were common, though hygiene was better among the Jews. Illness never left the human agenda and epidemics were common. The modern age was not free of such problems.

In our own century, the corona pandemic shook, frightened and affected the whole world, and it took many months and many deaths before medical science began to find ways of dealing with it. The Jewish response was largely traditional: fasting and repentance, prayer and Psalms, especially Psalm 91 (Yoshev B’Seter), which the Talmud (Shavuot 15b) describes as “a poem against pega’im (evil events),” and adds, ”Some call it a poem against nega’ím (plagues).”

Praying for God’s support is axiomatic in times of crisis. We could have utilized existing prayers for the recovery of the sick, but the pandemic was so severe and widespread that there was a fear that no existing prayer would have been adequate. We could have tried to compose new prayers for relief and protection; some congregations and rabbis did this, but finding themselves using phrases from the Psalms, many concluded that there was more to be gained by saying the Psalms themselves. The third rebbe of Lubavitch is reported to have said: “If we only knew the power of Psalms, we would recite them constantly.”

Which Psalms?

Joseph B. Soloveitchik saw a tension between distress-Psalms such as Psalm 22 and glory-Psalms such as Psalm 23. This meant that Psalm-saying was a form of wrestling with God. Psalm 91, in particular, plunged a person into the tension, combining the turmoil of fear with the calmness of safety. The resultant dialectic gave the Psalm an appeal when people faced pain, risk and fear, including imminent childbirth and approaching death. Jews often invoked this Psalm in times of illness. In circumstances of private or personal pain, Psalm 139 could have been the appropriate text because Verses 5 and 6 say, You hedge me before and behind, You lay Your hand upon me. It is beyond my knowledge; it is a mystery; I cannot fathom it. But when the broad public was suffering, Psalm 91 was often invoked, not least by European Jews during the long period of the Black Death.

The Psalm commended itself not only because of its dialectic but by reason of its powerful message and vivid language, reflecting the often horrific reality of terror by night and arrows by day, a plague that stalks in the night and destruction that rages at noon. These brought distress, dismay and destruction, well deserving the sobriquet of evil occurrences.

Yet the term “evil occurrences” is problematic. It seems to equate the strange category of “acts of God,” indicating natural rather than man-made disasters. “Acts of God“ is a technical legal term, not meant literally as something done by God but denoting an unforeseeable event that is outside human control and probably not preventable. In a theological sense, everything is residually traceable to God (Amos 3:6). The New Testament says, echoing BT Taanit 7a, that God makes the sun rise and sends rain “on the righteous and the unrighteous alike” (Matt. 5:45). Lawyers have not yet reached a consensus as to whether the pandemic, though it is certainly “an evil occurrence,” can be deemed “an act of God.”

A legal friend, Andrew Samuel, has drawn my attention to cases in contract law that, as Acts of God, are viewed as the outcome of natural causes of an extraordinary nature that cannot be anticipated or provided against by a party seeking to rely on it. We cannot yet decide whether the evil events in Psalm 91 are acts of God and whether it matters.

It must be added that the apparently evil forces in the universe are sometimes constructive. The evil inclination, the yetzer ha’ra, has its positive side. It is the force that impels a person to fulfill his ambitions. Without it, says a rabbinic dictum, no one would marry, have children, trade, or build a house. This is one of the paradoxes or tensions in rabbinic theology. In general, however, despite the constructive side to the yetzer ha’ra (evil inclination), Judaism has a bad opinion of demons and regards them as mischief-makers who cause evil occurrences.

We still have no definition of evil occurrences. In Psalm 91, evil occurrences are not defined but woven into the text.

The passage from tractate Shevu’ot that we have quoted comes in the course of a discussion about songs (poems) in the Temple. These include songs of thanksgiving accompanied by instrumental music, an example being Psalm 30. There are also songs in time of suffering, such as Psalm 91, where songs against evil occurrences are hinted at in verse seven and songs against a plague in verse 10. The distinction between pega’ím and nega’ím is not clear. Maybe it is a play on words since pega and nega sound so similar, but the midrash says that the two terms denote separate evil spirits. The Psalms scroll from Qumran hints at four types of pega’im that come in the four seasons of the year.

Outside influences were often blamed for the callous evil spirits and demons that haunted deserts, ruins or graveyards, where humans felt scared and unsafe. There might have been an earlier version of Psalm 91 that had crude descriptions of the evil spirits, but the psalmist might have reconsidered and refined his text. The talmudim and midrashim do not give an earlier version though that age probably favored noise, light or spells.

The origins of Psalm 91 cannot be stated with certainty, though it reflects the phobias and superstitions of the inter-Testamental period. It does not use the letter zayin, being thus an apparent lipogram. Lipograms are a literary device whereby an author deliberately omits from his oeuvre a certain letter or letters of the alphabet. An example from English literature is a book that never uses the letter “e.” Psalm 91 has no zayin, which Seligmann Baer explains in Siddur Avodat Yisra’el is an indication that protection from danger comes from trust in God, not from any weapon of war (zayin).

A number of other Psalms also partly or totally lack certain letters of the alphabet, for example Psalms 25, 34, 37 and 145. The reason for these omissions is not certain, though non-Masoretic texts of Psalm 145 (including the Dead Sea Scrolls) attempt to supply the missing nun. Our assumption is that the author of Psalm 91 omitted zayin intentionally. Otherwise we would expect zayin-words like mazzikim – destructive forces – and possibly zeman (a time or season), or zekher (a record or memory). There does not appear to be a lipogram in the Targum to Psalm 91, which has no problem with zayin-words such as mazzikei d’azlei b’leilya, destructive forces that go about by night (verse 5). Are we to conclude that the canonical text of the Hebrew, by leaving out any hint of mazzikim, has polemical implications?

Some of the sages think the author was Moses, and indeed the poet does share words and ideas with Deut. 32, which is Moses’ farewell speech; the midrash ascribes all of Psalms 90-99 to Moses. Other midrashim attribute authorship to the tribe of Levi. The Septuagint version of the Psalm has a superscription saying the author is David, though the Psalm comes later in Tehillim than Psalm 72:20, which is said to be the end of the Davidic Psalms.

The Targum says the Psalm was the work of King Solomon, thus echoing the ascription to Solomon of the three biblical works of Shir HaShirim, Mishlei and Kohelet. The Targum sees the Psalm as a dialogue between David and Solomon. Supporting a “dialogue” theory, there seem to be several voices: Speaker 1 in verses 1-2, Speaker 2 in verses 3-8, Speaker 1 in verse 9, Speaker 2 in verses 10-13, and God Himself in verses 14-16.

Demonology is rare in the Bible and not very significant, in contrast to the New Testament. The latter has an emphasis on the demon hierarchy led by Satan, “the prince of the powers of the air” (Eph. 2:2), who is hostile to God and to Jesus (Matt. 4:1, Mark 1:12-13, Luke 4:1-13, II Cor. 11:3, Rev. 12:9). In Judaism, it is only in later legend and literature that he assumes a personality of his own. He is not taken literally or given doctrinal status.

The Hebrew Bible is trenchantly opposed to magic though some purported acts of sorcery are claimed to be for the sake of God. Actually everything in the world traces back in some way to God. The Kabbalah attempts to systematize Jewish demonology and notes influences from Arabic, Christian and ethnic sources. In the Talmud and midrash the demonological material is diffuse and often rather primitive.

Certain demons are said to hold sway between particular hours and days and hence, people should not drink water on Wednesday or Sabbath eves. Solomon employed demons to work on the Temple building project. Psalm 91 should be recited before taking a nap on Sabbath afternoons.

While the general mood and message of our Psalm are clear, there appears to be some confusion as to who or what it is that arouses the psalmist’s distress. Are there a series of specific problems, or is there a general malaise, which may be caused by natural forces, energies, insects, animals or enemies? There are also exegetical problems.

Verse 1 could a) be a call for protective action by God who (metaphorically) dwells in secret places On High and sees all that is happening on earth; b) a call to the pious believer to place his trust in God; or c) an assurance that the believer is fortunate to have God with him.

The Psalm might originally have commenced, Ashrei – happy is... parallel to Psalm 1:1. This would have produced a text like Ashrei (the expanded Psalm 145) with an opening statement, Ashrei yoshev b’seter – Happy is the one who dwells in the covert (of God).

In Verse 1, Shaddai – a rather rare Divine name – might be a foil to shed, a demon. The Shadow of God might reflect a notion that demons have no shadow (TB Yev. 122a etc.). Both interpretations are however only suppositions. Rav J.B. Soloveitchik derives Shaddai from the root sh-d-d which suggests God’s power to overturn the laws of nature according to which wild beasts tend to pursue and harm their prey.

There are six evil demonic forces specified in Psalm 91, representing the main evil energies – external or internal – that strike fear into people’s lives.

The fowler’s trap (Verse 3) is mental and physical entanglement, presumably when a person is caught by dangerous traps placed by a demon. Hosea 9:8 refers to a path strewn with traps.

The destructive plague is infectious epidemics, maybe brought on by witches’ spells. S.R. Hirsch thinks dever havvot might denote impending but not yet actual pestilence.

The terror by night (Verse 5) is night-time assaults on person and property; presumably the night’s darkness itself is a source of fear.

The arrow that flies by day is sharp pain caused by injury or disease that pierces a person like an arrow.

The plague that stalks in the darkness (Verse 6) is a contagious disease that spreads by stealth and does not heal easily without the daytime warmth and sunlight (Mal. 3: 20).

The scourge that ravages at noon is a demon that boldly does harm in the light of day when the extreme heat of the midsummer sun causes pain (Deut. 32:24).

Verse 13 hints at injury caused by animals. The verse has a series of animal names, which the translators render in various forms. There are cubs and vipers (JPS Bible; NEB has asp and cobra; Oesterley has lion and adder; Hirsch has jackal and asp). All cause mischief. Harm is carried by the cub’s teeth and roar, the asp’s venom, the dragon’s poison, and the viper’s tongue. Then come lions and asps (JPS Bible; NEB: snake and serpent; Oesterley: young lion and dragon).

There is much discussion over whether k’fir is a young lion, a powerful menace with a frightening roar; NEB refers to creatures that slither along the ground. In the verses added to the Grace After Meals, k’fir is possibly a heretic, from the root k-f-r, akin to kofer b’ikkar – one who denies a basic religious tenet. In a Festschrift for Louis Ginzberg, Robert Gordis, supported by Reuven Hammer, thinks that in Psalm 34:11, k’firim contrasts with dor’shei HaShem – those who seek God. In Psalm 91, the context probably requires a non-theological view of k’fir.

Whatever the challenge, God tells Israel, I am the Lord who heals you (Ex. 15:26). As the Most High (Ps. 91:1) who dwells above His Creation, He watches over the world as Israel’s Guardian (Psalm 121; Deut. 32; Rashi, Ibn Ezra). He will cover you with His pinions (Verse 5) - like an eagle which hovers over its young (Deut. 32:11; Rashi). His truth will be a shield and armor (buckler) – His promises are dependable.

You need not fear – do not give way to depression, abandonment and terror; rely on God to save you from disaster.

It shall not reach you (Verse 7) – you will be spared, like the Hebrew slaves who emerged from Egyptian bondage and crossed the Red Sea on dry land despite pursuit by Pharaoh.

No harm will befall you (Verse 10) – you will be safe and prosperous; your children will bring you joy.

No disease will touch your tent – you and your home and family will be safe and unharmed (TB Sanh. 103a).

He will order His angels to guard you (Verse 11) – the harmful demons will be overcome by protective angels brought into being by observance of the commandments (Maimonides).

They will carry you upon their hands (Verse 12) – they will attend to the smallest detail of your safety.

Lest you hurt your foot on a stone – you will be safe from the slightest injury.

You will tread on cubs and vipers (Verse 13) – “tread” may be metaphorical; if meant literally, young lions in messianic days will become as tame as at the time of Creation (Ezek. 19:3; Nahmanides).

I will answer him... rescue him... honor him – I will spare him from harm and treat him well (Verse 15).

I will be with him in distress – when the world is in distress, the Creator feels their pain and like His creatures, is in need of sympathy and support.

I will let him live to a ripe old age (Verse 16) – assuring him that God is concerned for his wellbeing. A number of Psalms such as Psalm 23 end with a similar blessing. And (I will) show him My salvation – in messianic times God will prevent the evil forces and wild beasts from doing harm.

I shall establish peace in the earth… and I shall cause the wild beasts to desist (Lev. 26:6) – there will still be wild beasts but their wildness will be blunted. Nahmanides says that originally they were placid but after Adam’s sin, man learned to defy God and the animals learned to hunt their prey (Ezek. 19:3). In future, the cow and bear shall graze, their young shall lie down together: and the lion, like the ox, shall eat straw (Isa. 11:7-8).

Though everything that happens in the world eventually traces back to God, Jewish usage is reluctant to blame God for the destructive effects of demons or of human antagonists. The tendency is to blame ourselves, to say umip’nei hata’enu, it is because of our sins. Nonetheless, God protects the victim because He is devoted to Me – he yearns for my presence and blessing; He knows My name – he knows I am concerned for my world; He calls on Me – William Moran interprets obeying a sovereign’s laws as the best tribute.

Throughout the Psalter, the poet faces adversity and calls on God for deliverance. In Psalm 91 the speaker is not an individual who suffers on his own but symbolizes humankind, who are all in pain. The Psalm is important because it is universal, and like other biblical passages (e.g. Sam. 14:6), it presents us with a series of theological axioms: pain exists, pain is evil, human beings are susceptible to pain, God wishes to eradicate pain, God is able and willing to save us from pain: if we cry out in pain, God hears the cry and rescues us.

It would be easier if the problem of pain did not exist, but God has no obligation to create a perfect world. As opposed to the Christian doctrine of original sin, which basically says that the human being has an inherent flaw that can be overcome by turning to Jesus, Judaism sees the problem as moral, not spiritual.

The world had a primeval innocence that was lost at an early stage when Adam was not morally mature and Creation lost its glory. The original innocence will only be restored at the messianic redemption. Regaining the pristine innocence will require a moral struggle. Psalm 91 is a fundamental dimension of the story of the struggle. ■

Rabbi Dr. Raymond Apple, AO RFD, is emeritus rabbi of the Great Synagogue, Sydney, and past president of the Orthodox rabbinate of Australia and New Zealand. He was nominated as one of the 20 leading Australians. His books include Biblical People and New Testament People.

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });