Israel is not democratic, should adopt UK parliamentary system

It would be more fitting to replace Israel's non-democratic system with one similar to the parliamentary democracy practiced in the United Kingdom.

It used to be that Italy was the country with the most general elections within an unrealistic timespan, but now Israel leads the field.

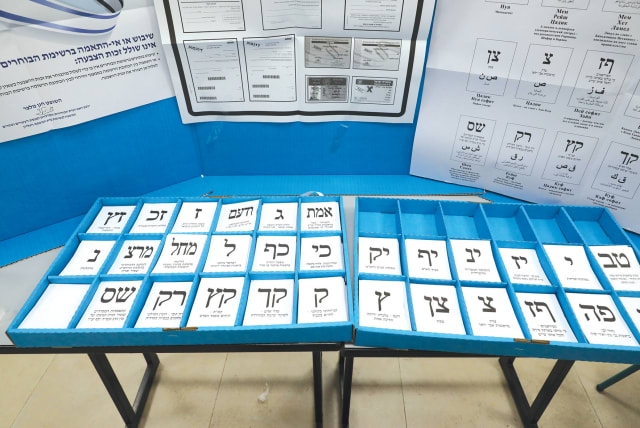

On November 1, Israelis are going to the polls for the fifth time in three and a half years to elect yet another new government. At the last election in March 2021, there was a choice of 53 parties. Many announced totally irrelevant aims with only the support of the 100 original signatories that are required for registration and no hope for wider public endorsement.

Such an administrative nightmare and associated cost can be easily eliminated by a large increase in the required number of founding signatures, and by inflating the current registration fee of NIS 2,333. Last year, 13 politically extremely diverse parties made it into the Knesset. With such a number, it is almost impossible to broker an agreement on any proposed legislation. In our current system to achieve a government, led by a majority party that will be able to fulfill its declared manifesto, it is necessary to further increase the electoral threshold to exclude more of the smaller parties that are able to make or break proposed legislation.

The low threshold, in combination with the nationwide party-list system, makes it almost impossible for a single party to win the minimum of 61 seats needed for a majority government, and this leads to the formation of an inevitable coalition. But a country cannot be successfully governed when in a narrow coalition government, one or another minority party conditions its vote on impossible demands. Unfortunately, that is a repeated situation in the Knesset.

Even if all that was changed, however, Israel would still not have a truly democratic system of government.

Why is Israel not democratic?

The fundamental principle of democracy stems from the Greek words demos, meaning people, and kratos, denoting power. So democracy can be thought of as “power of the people by the people and for the people.”

An examination of the structure of our political parties demonstrates that this is not the case in Israel. Take Likud as an example. In the largest party in Israel, just 150,000 members – at a generous estimate – are eligible to determine who should be on the list to be their delegates in parliament.

In reality, the turnout for its primary election this year was approximately 50%. In some parties, the delegates are even selected by the leadership that determines the order of probability to succeed as an MK.

This whole system I have described does not only deny our citizens the right to select their representatives who will govern, but by its very nature produces a government in which the conflicting interests of each constituent party prevent any productive policy to benefit and further the varying needs of different areas or communities.

Israel has progressed from the socialist-based philosophy of yesteryear that built the foundation of our state to an important player among the nations of the world. In concert with our Western democratic partners, we condemn the regimes that prevent freedom of expression for their population. Yet our Knesset members are delegates of the parties, without any input from the citizens, instead of being their voted representatives as is the case everywhere else in the Western world.

Israel should adopt the UK parliamentary system of democracy

In the 21st century, it would be more fitting to replace our non-democratic system with one similar to the parliamentary democracy practiced in the United Kingdom.

They have just three main parties with a realistic chance to form a national government: Conservatives, Labour and Liberal Democrats. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland also have, in addition to their representation in Parliament, their own national assemblies. Few others, except perhaps the Greens, are of consequence.

For voting purposes, the country is divided into 650 geographical voting districts known as constituencies, each represented in parliament by its own member. In general elections, any registered party within a designated voting district can put up its candidate for election. The eligible residents of that constituency will then vote for one candidate of their choice, and he or she with the highest number of votes will become their Member of Parliament. It is important to note that in their acceptance speech, MPs will invariably stress that they will now represent all residents of the area, without regard to their party affiliation and voting record.

That pattern is repeated nationally, and the party ‘first past the post’ that reaches the magic number of 325 elected members forms the government made up of its own MPs.

As each area has predominant interests – some agricultural, others industrial, etc. – their MP will work with relevant ministries to promote those needs.

Unlike here in Israel, where MKs are not accountable to the voters and are generally not approachable, MPs make themselves available once a week in their local area office for members of the public to seek advice for their personal problems or concern in matters that affect government. If considered relevant, the MP will write to the appropriate minister and the whole correspondence is then forwarded to the complainant. That is democracy.

If such a system were to be implemented in Israel, the attitude of our MKs would radically change for the better, because in order to retain their position, they would have to be accountable to, and show interest in, their constituents rather than acting according to the dictates of their ego. As such, a change needs to be approved by Knesset. It would probably be strongly opposed, just as turkeys would never vote for Thanksgiving.

A workable compromise solution could be that half of the 120 MKs would be appointed by the parties, and the remainder would become the elected representatives of 60 constituencies. That would be more democratic and would bring Israel’s system of government closer to that of other Western democracies. ■

The writer, at 98, is the oldest working journalist and broadcaster in the world.

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });