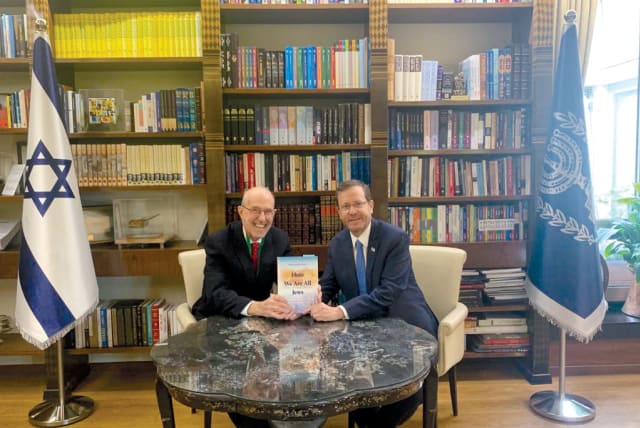

'Here We Are All Jews': Jewish champions behind the Iron Curtain - review

In his new book, JonathanPorath recounts his most extraordinary experiences on his 175 trips to the USSR in the period between 1965 and 2019

Inspiration sometimes emerges from the most broken of places. Those that are lost can, at times, become the compass for those who believe they have already arrived. Such was the case for Rabbi Jonathan Porath and his brave high school students who sought to secretly reach and encourage the “lost” Jews behind the Iron Curtain of the Soviet Union.

In his new book, Here We Are All Jews, Porath recounts his most extraordinary experiences on his 175 trips to the USSR in the period between 1965 and 2019. Unexpectedly, these missions to strengthen Judaism among their co-religionists trapped in a communist regime ended up solidifying the Jewish identities of Porath and his followers and changing the course of their lives forever.

Porath’s father was a fourth-generation Jerusalemite whose ancestors had journeyed to Israel with the students of the Vilna Gaon. However, Porath’s grandfather moved with Porath’s father to perform shlichut (Jewish outreach) in America. Porath grew up in Chevy Chase, Maryland, and was raised to be a pulpit rabbi like his father and grandfather before him. He was an active United Synagogue Youth member as a teen and stayed in touch with the staff afterward. Porath felt he had leadership in his blood, so when the opportunity came to lead a group of USY high schoolers on a life-changing mission to Russia, Porath courageously stepped forward.

Interested in saving Russian Jewry

Porath first became interested in Russian Jewry after reading Elie Wiesel’s famous book, The Jews of Silence, in which Wiesel admonishes world Jewry for their neglect of and indifference toward Jews still suffering in the post- Stalin era. Porath was also enthralled by Russian tsarist history, leading him to study Russian history and language at Brandeis and, then, Hebrew University in 1965. This knowledge would later become invaluable on his future expeditions to Russia.

The Soviet Union displayed an open love for tourists, using it as a public relations opportunity to present itself as an open-minded, welcoming country to the non-communist West. For this purpose, the USSR set up Intourist, a government department that accompanied and led tour groups to state-approved landmarks. Intourist guides were responsible for showing the grandeur of the great “Soviet Power,” while, at the same time, preventing their group from interacting with locals and informing of any suspicious activity to their superiors in the KGB.

Understanding the great risk of bringing undercover Jewish teenagers to the Soviet Union, Porath worked meticulously on the preparation for his first trip with the USYers. After all, their parents and congregation members were trusting him to deliver an educational, meaningful, and safe tour of Jewish Russia to their teens. Porath led an extensive orientation to review all the security concerns with the students. It was forbidden in the USSR to bring in any “anti-Soviet” material, such as Wiesel’s book, Israeli currency, or any obvious Jewish items. Since their luggage would be thoroughly searched at customs, and their hotel rooms were likely to be bugged, he cautioned them not to be critical of the Soviet Union verbally or even in their personal diaries. “We sang the Shabbat prayers ever so softly,” Porath writes, “so as not to arouse the attention of the ever-present Soviet floor lady, who watched every hotel floor like a hawk.”

The trip was described to the students as a “double tour program,” in which they would be typical tourists from nine to five; and then, in the early mornings and late evenings, they would clandestinely seek out Jews. They were not allowed to wear kippot (ritual skull caps) in public and were warned not to be seen interacting with the locals. Porath came up with creative ways to identify Soviet Jews without alerting the informants. Fiddling with a Magen David charm on a necklace, whistling the tune to “David Melech Yisrael” in public, and quickly saying “Shalom” to passersby became secret codes of connection. Even in synagogues, where everyone was Jewish, the student tourists had to be careful, as the gabbais (synagogue beadles) had official roles sanctioned by the state and were charged with keeping visitors and locals apart and reporting to the Soviet Ministry of Cults when necessary. Once, when a gabbai was giving a tour of his synagogue in Leningrad, he was trailed by one of the synagogue’s old-timers, who kept repeating a statement to Porath’s group in Hebrew, a language the gabbai did not understand: “It’s all lies and a cover-up. It’s all fake.”

During one of their tours in Odessa, the Intourist guide showed Porath’s group the new Jewish cemetery. Porath urged the guide to bring them to the old Jewish cemetery nearby, but she refused, saying it was closed to the public. Porath slipped away from the group and was horrified to find the “tombs smashed, gravestones uprooted, and Russian graffiti on the monuments.” The guide figured out where he had gone and was extremely tough on the group for the remainder of their trip. Two days later, at departure customs, the group’s belongings were ransacked. Porath had no doubt it was because of her negative report. Similarly, in 1973, at the Moscow airport, the group’s personal items were thoroughly searched, and nearly 100 of them were confiscated. Their hotel rooms were raided, and more of their possessions went missing. Porath overheard the floor lady talking about his USY group, calling them “the one from Israel.” In 1974, Porath led his final USY trip to the Soviet Union due to heightened security concerns as tensions increased in US-Soviet relations. He described leaving Soviet Moldavia that year as an “exit from hell.”

However, Porath was convinced that his perilous missions were well worth the risks involved, as the Soviet Jewish population sorely needed whatever outside support they could get. In order to identify as Jewish, even in a small way, local Jews were endangering themselves. Merely by being within 10 feet of a synagogue, these Jews were putting their reputation, career, and family on the line. Informants were everywhere; and being a proud Jew and a loyal Soviet citizen were incompatible. The USYers distributed as much Jewish material to the Soviet Jews as they could sneak through customs, items such as, talitot (ritual prayer shawls), mezuzot (ritual amulets placed on door posts), tefilin (phylacteries), siddurim (prayer books), and Russian-Hebrew dictionaries. A Leningrad Jew compared his group to the biblical Joseph of the 12 tribes who never forgot his long lost brothers. Upon hearing that Porath was a rabbinical student, the Georgian Jews asked if he would accept the position of chief Ashkenazi rabbi of Soviet Georgia. They even offered to pay for his apartment and to find him a Jewish shidduch (marriage partner). In Moscow, Porath read aloud from the help-wanted section in an Israeli newspaper that he had smuggled in with him: “Wanted: Teacher in Jerusalem! Job offer: Engineer in Tel Aviv.” The Russian audience eagerly responded, “That’s my job! Save that one for me!” Yet, despite their excitement, “They had greater faith in the coming of the Messiah than in their ability to leave Russia,” Porath writes.

In 1970, a group of 16 Jewish refuseniks attempted to hijack a civilian aircraft and escape to the West. Even though the attempt was unsuccessful, it drew international attention to human rights violations in the Soviet Union during the height of the Cold War and resulted in the temporary loosening of emigration restrictions. Jews were suddenly able to apply for visas and leave the USSR for good. On the 1973 USY summer trip, the group was assigned a Jewish Intourist guide named Luba. She became close with the group and even showed them her Russian passport with the word “Yevreika” (Jew) on it. She remained in contact with Porath after the summer. In 1974, when Porath was leading another trip, Luba asked to meet with him. She confided to him that she wanted to apply for a visa to leave Russia; however, it wasn’t a simple matter for Intourist guides. Because Intourist was a government department, she had a quasi-security status, and attempting to leave the Soviet Union would brand her as a traitor. If she applied for a visa, she would undoubtedly be fired and might not even be granted an exit permit. Porath could only console her. Two years later, in 1976, he received a long-distance phone call from Rome. It was Luba; She had just left Russia and needed financial help to go to the United States. Porath reached out to members of his congregation and arranged for them to meet with Luba and give her the money she requested while they were on their vacation in Rome. Several months later, Luba settled happily in Albany, New York.

In 1984, Porath and his wife, Deena, along with their four children, made aliyah and moved to the Ramot neighborhood of Jerusalem. In the early 1990s, over half a million Soviet Jews arrived in Israel. During 1990 and 1991 alone, 450 Jewish olim (immigrants) arrived from the USSR every single day for the entire 24-month period. From 1992 through 1995, another 250,000 arrived. Porath, along with his neighbor Avraham Shafir, helped the Russian olim in their neighborhood by collecting used furniture for their empty apartments. They called themselves The Neve Orot Neighborhood Absorption Project. In those early years, Porath’s absorption project presented each new family with a refrigerator and a mezuzah. For “even if they had never seen a mezuzah before, it was the sign of a Jewish residence, and they were now at home.” They opened a neighborhood clothing gemach (free loan society), where the olim could “take what they needed at no cost.” Later, the project helped them find jobs and offered interest-free loans to get them started. Volunteers organized brit milot (ritual circumcisions), officiated at funerals, and took the elderly to the Western Wall for the first time. Porath led a model Passover Seder at the local ulpan (Hebrew language school), where he met Jews that had never even heard of the Exodus story. By 1993, the project had raised over $137,000. At the Knesset, the Ministry of Religious Affairs presented the Neve Orot Neighborhood Absorption Project with the Israeli government’s National Prize.

In 1993, Porath joined the Joint Distribution Committee’s Russian Department, whose goal was to “Judaize the Jews.” This meant establishing kosher restaurants, importing Jewish libraries, and setting up self-sufficient Jewish non-governmental organizations in Russia. The JDC launched SEFER, a mission to integrate Judaic studies and Jewish life into universities all over the former Soviet Union. Porath’s job was to organize local partners who would further SEFER’s aims. He traveled all over the country, from the farthest north to the Siberian east, setting up local infrastructure for the Jewish population of the small towns. Porath worked with Rabbi Yossie Goldman, the director of Hillel at Hebrew University, to bring the “Hillel model” to the former Soviet Union, an enterprise that became a stunning success. The JDC also built YESOD, a Jewish community center in St. Petersburg, where Jewish weddings, international speakers, and municipal conferences were held.

When Porath began writing his book Here We Are All Jews, he decided to reach out to his former USYers to interview them and see what impact the trip had had on their lives so many years later. He was surprised and elated to find that many had become activists and leaders in the Soviet Jewry movement. More than a quarter of them had chosen a career in the Jewish private sector or founded their own organizations. Some returned to Russia to make more contacts and support the refuseniks. One even became the chief rabbi of Poland. For those who did not become Jewish professionals, the trip was still extremely impactful in a spiritual sense. “I became a Shabbat observer. I never took being a Jew for granted again,” for at the time, “we were certain that the Soviets would never Let Our People Go,” a former USY field member explained. Others vowed to keep kosher after the trip and have lived Torah-observant lifestyles ever since.

In 1969, the first group of Porath’s students embarked on a trip to encourage Soviet Jewry to never lose faith. Over 50 years later, they still felt “strengthened by their courage and dedication, their love of Torah and the Jewish people, and their feeling for Am Yisrael.” Elie Weisel, the author of the book that started it all, became a close friend of Porath’s over the years and influenced him to write his book. Porath’s aim for Here We Are All Jews is to develop within the reader a greater feeling of Kol Yisrael areivim zeh bazeh – “the fate of the entire Jewish people is intertwined” – a notion of brotherly responsibility and love that became Rabbi Porath’s purpose. ■

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });