The Balfour Declaration rekindles hope - opinion

How it really was! I discovered the Balfour Declaration… It rekindles hope!

Did you ever wake up and ask yourself whether the memory that just popped into your head came back in a dream or just as you awoke? It happens to me often. The latest was quite wonderful. I relived a real incident that took place when I was about 11 years old. In my afternoon Hebrew school in Toronto, Talmud Torah Eitz Chaim, I made a precious historic discovery. We had an official document of the British government in our possession written with the heading, “Foreign Office,” which was signed by Arthur James Balfour.

Not only that! It was addressed to Lord Rothschild. For sure I knew that name, even at age 11, and may even have learned of Lord Balfour in our school lessons in the then O-so-British elementary school curriculum. Before serving in other cabinets he was prime minister of the United Kingdom from1902 to 1905.

(I think we studied more British history than that of Canada.)

How did all of this come about?

“Smart kids” often became “monitors.” Their task was to wipe the blackboard clean and perform sundry tasks or carry notes from one teacher to the other. One afternoon, my Hebrew teacher, Mr. Abella, asked me to remove the prayer books (siddurim) from the large corner cupboard, dust them and replace them. As I proudly carried out this task, I discovered at the bottom of the pile a sheet of typed paper encased in a brown framed glass. It was dust-covered so that only hard work could break the years-old crust. I swiped away enough of the thick dust to recognize that this was a very important document. I asked permission to take it to the bathroom to wash away the years.

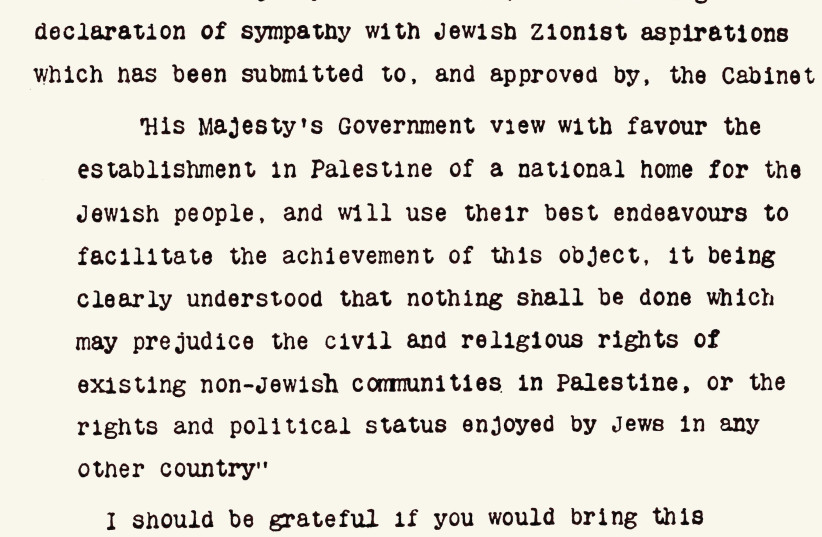

I returned thrilled. Thrilled. We lived as Jews in a British country, as Canada was then. Imagine, “His Majesty’s Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a Jewish homeland…” A Jewish homeland. A Jewish homeland for our homeless people.

“Teacher,” I said in Ashkenazi Hebrew, and continued in Yiddish. “This is very important.”

He was kind. He did not laugh at me, nor poke fun at me for believing this was the original. After all, I was a precocious 11-year-old, but still, I was just 11. Our cheder was one of the three centers of my life; the other two being naturally, public (Canadian) school and family. Writing this I see though that the total time spent in school (five-and-a-half hours a day) was less than the Jewish components: cheder and family. Both of these filled my conscious and unconscious mind: in my case, as opposed to the non-Jewish school.

When we add to the Jewish component youth prayers on Shabbat morning (at which we could belt out the hit tunes for the popular prayers with total juvenile joy and top-of-the register delivery) and Hebrew school on Sunday, why these certainly tipped the scale.

In short, I liked being Jewish. I also liked being Canadian, reaching puberty in a time of the just war against the Nazis.

And even prouder because Arthur Balfour, in the name of the entire British cabinet, endorsed “Jewish Zionist aspirations.”

My mother told me that in Poland when the news of the Balfour Declaration reached her shtetl, the girls made blue and white dresses and joined the male contingent in dancing and singing. I know part of one of these Yiddish songs: “Joy, joy, Palestine-joy. We shall go there, we shall build there, Joy-joy, Palestine-joy.”

My mother also told me about the fears that gripped the Jews in Poland around Christmas and Easter. Relatives and friends who were a bit older than I related their memories of Poland in the 1920s and 30s, always with recalled hatred. It is no wonder that antisemitism, created and sponsored by most of the Polish Catholic Church and by the ruling party flourishes again on that accursed soil. “Why? What for and for what kindness, should we serve Poland?”

That song my mother taught me was sung in private youth gatherings in the 1920s. Too late for my father who served in the new Polish army in 1919 as soon as Poland became independent. My father was smart enough not to be in the march on Kiev, where his battalion was wiped out. That mad march on the Ukraine was Poland’s first order of business, to try to rebuild the Polish Empire.

I fear for those few decent Poles who dare speak out against Jew-hatred. They face not only social ostracization, but outright threats to income, life and limb.

Let Poland and its racism be a lesson for all who foster racism against non-Jews in this country. Perhaps this should be one of our first resolutions for the coming Hebrew New Year.

Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are referred to in the Mahzor (holiday prayer book) as days of judgment of the world as a whole. It does seem that the entire world has been beset by a chain of catastrophes. It is as though all of the bleak parts of a beloved prayer are befalling us.

That prayer, Unetanneh tokef, is central in the High Holy Day rites of the Ashkenazi, Italian and Moroccan Orthodox traditions. It is found as well as in the Conservative and Reform liturgy. Its words stir the heart as they are chanted in a dual duel between life and death:

“Who will live and who will die; ... who by water and who by fire/, who by sword and who by beast,/ who by famine and who by thirst,/ who by earthquake and who by plague./ Who will stay in place and who will wander/…..who impoverished and who enriched....”

This past year we have seen floods, forest fires, and plague; landslides, earthquakes and famine and again plague across all seven continents.

Israel has suffered all of these – fortunately without famine – and with limited deaths from the corona plague.

The battles go on. Some are natural catastrophes, some are caused by human neglect and criminal acts.

The prayer I quoted above concludes with hope. The evil decree can be averted if we repent, pray and give charity. These combined acts may improve the individual. But after the Holocaust, we question why so many innocent children, men and women including those millions who prayed and repented and did good deeds were not saved from the evil decree.

So why observe our Holy Days? Because our tradition and its acts and words of beauty keep that flickering flame of hope alive.

That faltering flame teaches us that we must correct our own selves and act justly. Without that millennial hope how could our people have survived and revived?

Hope was rekindled by Lord Balfour after almost two millennia of exile. Hope will always continue to move many of us to strive to be decent, part of a just people. It is harder and harder to carry this flame of hope in the face of what we have gone through and are still going through.

But remember this:

We kept trying. Across millennia.

We will keep trying.

The writer dedicates this column to the memory of a friend and colleague who carried hope and the love of humanity and of Zion in his heart: Rabbi Richard Hirsch died at age 95 on the day this column was written.