Cardinal Newman and self-conscience: Commentary on Israeli politics

Most people get confused when speaking about tolerance. They often use this word when in fact they mean “apathy.”

These days, the word “tolerance” has become highly popular as are the words “pluralism” and “democracy.” These terms are used so often that one would hope most people have a proper understanding of their meanings. This is, however, far from true. In fact, it seems that the more these words appear in our papers, books and conversations, the less they are comprehended. They are often used in ways that oppose the very values they stand for.

For example, when we focus on the word “tolerance,” we can identify the problem. People feel proud when they are able to claim how tolerant they are. They see themselves as broad-minded people, who really have little objection to any thoughts or views of others, since all attitudes and outlooks on life should be permitted in a free society. These views are then linked with values such as pluralism and democracy.

The shallowness of such attitudes, however, is abundantly clear. If society were indeed prepared to be tolerant on all fronts, it would turn into hell and become self-destructive. It needs little effort to explain that we cannot be tolerant toward antisemitism, racism, crime or sexual harassment of women and children.

Suddenly we realize that there are moral principles that cannot be violated, and we should stand by these principles, come what may.

Most people get confused when speaking about tolerance. They often use this word when in fact they mean “apathy.”

Tolerance does not mean apathy

Alexander Chase once wrote, “The peak of tolerance is most readily achieved by those who are not burned by convictions.”

Ogden Nash said as follows:

“Sometimes with secret pride I sigh,

To think how tolerant am I;

Then wonder which is really mine:

Tolerance, or a rubber spine?”

Indeed, many times it is indifference that makes people believe they are tolerant. It is easy to be tolerant when one does not care about values and principles or about the moral needs of society and one’s fellow man.

As the saying goes: “If you don’t stand for something, you will fall for everything.”

Tolerance has become the hideout in which many people turn their egocentricity into a virtue.

Looking at today’s Jewish scene, we see a similar phenomenon. This time, it is “unity” which has become a popular word used by the various factions within the Jewish world. All of them speak of unity, and each one accuses the others of a lack of commitment to that unity.

NOBODY DOUBTS that the unity of the Jewish people is of crucial importance, and it is certainly threatened today. Unless stopped, the new Israeli government seems to undermine any unity among Israelis. It is dangerous and embarrasses authentic Judaism. It is creating enormous problems that are detrimental to the future of Israel and the Jewish people.

We are fortunate to have great Orthodox rabbis, such as Rabbis Yuval Cherlow and David Bigman, both heads of yeshivot, and many other Orthodox rabbis, all of whom have taken a clear stand on this matter. Together, they have rejected the extreme views of some members of this government who do very little to encourage unity.

Still, we have to ask ourselves if unity really is the highest value to strive for.

To many, the refusal by different religious and secular denominations to recognize “the other” is seen as a lack of both courage and tolerance. And indeed, sometimes it is. But it would be a fundamental mistake to believe that this is the whole story.

Unlike politics, in matters of religion and ideology, unity is not the priority. What is a priority is personal conscience and authenticity.

Let us take a look at Judaism’s history. Should Avraham have made a compromise with the world in which he lived for the sake of unity? Wouldn’t this strong-minded man have been more influential had he not taken the stand he took? Clearly, Avraham created a great amount of emotional upheaval. He and so many prophets after him, like Samuel, Yeshayahu and Yirmeyahu, were violent protesters and refused to go along with the values of their times.

No doubt, many saw them as inflexible extremists who shattered the tranquility of their societies. Moreover, we can be sure that many “modern-minded” people in those days condemned them for their outdated ideologies and refusal to go along with the “up-to-date” values of the day. It was surely not unity which motivated these prophets.

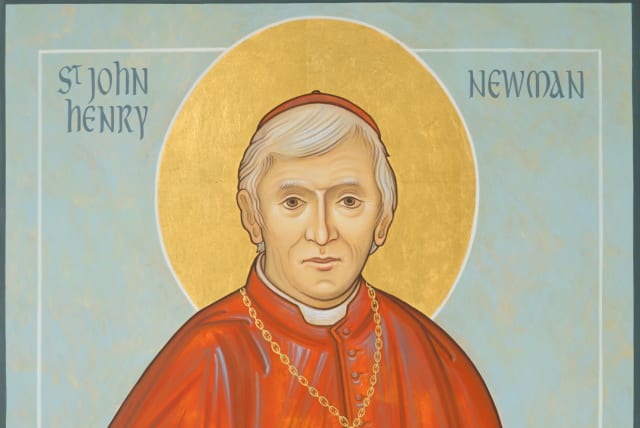

IT MAY be worthwhile to take notice of a major controversy that plagued the Christian world for a long time. One of the most famous Anglican theologians in the 19th century was John Henry Newman. After holding a prominent position in the Anglican Church, he decided to join the Catholic Church and later became one of its most prominent cardinals. At the time, this move became a topic of intense debate throughout the Christian world. Many admirers of Newman felt he should have stayed in the Anglican Church.

They correctly believed that from the point of view of unity and reconciliation, he would have succeeded in making a major contribution toward bringing both churches closer. He would have been seen as an authoritative Anglican with a strong leaning toward Rome. The Anglican Church would have been unable to ignore his position, and he could have brought both sides closer. But the moment he became a Catholic, the Anglican Church wrote him off.

When asked why he had not taken that route and remained with the Anglican Church, Newman made a very important observation. After admitting that he would indeed have been much more influential had he stayed in the Anglican Church and contributed to a much needed reconciliation, he added that this option was not open to him. His words are most telling: “One cannot put reconciliation over one’s conscience. In matters of truth, one makes a choice between what one considers to be true and what one considers to be false.”

Newman had come to the conclusion that the theology of the Anglican Church was erroneous and had to be rejected. To stay in the Anglican Church would have been a compromise and, as such, a sign of weakness and lack of courage.

THIS HISTORIC event should be important for Jews to keep in mind when debating the authenticity of the different religious and secular movements. Neither Jewish identity nor the nature of Judaism can be decided simply on the basis of what will do less harm to Jewish unity. This is an instance where personal conscience, i.e., one’s perception of the truth, decides.

In Orthodox Judaism, the Torah and oral tradition are rooted in the Sinai experience. The Torah is seen as a verbal revelation of God’s will, and no human being may reject anything stated therein. Likewise, the oral tradition is believed to be the authentic interpretation of the text and, while open to debate, may not be simply rejected or ignored. Obviously, anybody has the right to challenge this belief and reject it. But nobody should impugn the Orthodox for holding its ground and not compromising on these fundamental beliefs.

To Orthodox Jews, this is a matter of truth or falsehood. The Conservative and Reform movements have different views on all these matters and believe that the Orthodox view can no longer be upheld. For them, Orthodoxy does not represent the authentic nature of Judaism. That these movements cannot recognize each other as genuine representations of Judaism is, therefore, not the outcome of weakness but of principle.

The only legitimate argument is that a new philosophical/religious approach could pave the way toward reconciling all these various opinions without compromising each one’s personal conscience and authenticity. This may well become the major challenge for future Jewish thinkers and halachic authorities.

But as long as this is not the case, one cannot expect these movements to compromise their positions on matters that are of the greatest and most primary importance to each.

The only exception is when decisions are made in the name of the Torah which in fact are wrong in the eyes of all denominations and violate God’s name.

Cardinal Newman would have agreed.

The writer is dean of the David Cardozo Academy in Jerusalem. He is the author of many books, including the bestseller Jewish Law as Rebellion. His thoughts are discussed on many media outlets, and he is also an international lecturer. Find his weekly essays at www.cardozoacademy.org/