The Lost Tribes of Israel: Who are their descendants today?

There is a group of people looking to uncover the truth behind the lost tribes in order to determine where they went and to integrate them back into the Jewish people.

For millennia, the idea of the lost tribes of Israel has been a topic of intrigue for believers and non-believers alike. There is certainly no debate that following the destruction of the First Temple, most of the 12 tribes have been scattered across the globe. From the words of Israel’s prophets to the tales of the Sambation River to this day, the question remains: Where did they go?

Well, that was anyone’s best guess – until today. There is a group of people looking to uncover the truth behind the lost tribes in order to determine where they went and to integrate them back into the Jewish people.

What makes someone lost? That is the first question to explore. It appears there are three types of “lost” Jews: those claiming to be descendants of biblical tribes; those who converted decades or centuries ago; and those who have been forced to hide their Judaism due to fears of persecution.

Israel-Jewish rights activist Rudy Rochman has been at the forefront of Israel activism for much of the past decade, after founding the Israel student group on campus at Columbia University in New York City. As Rudy progressed throughout the years, his views and priorities evolved for how to best approach empowering the Jewish people. From the get-go, and more recently, Rochman has faced criticism from a small but loud contingent on the far-right and far-left – those on the far-right call Rudy a “Palestinian apologist” or a “leftist threat,” while those on the far-left say he is a “right-wing extremist” and “messianic.” Nevertheless, Rochman has kept his head high and continues to work towards advocating on behalf of the Jewish people.

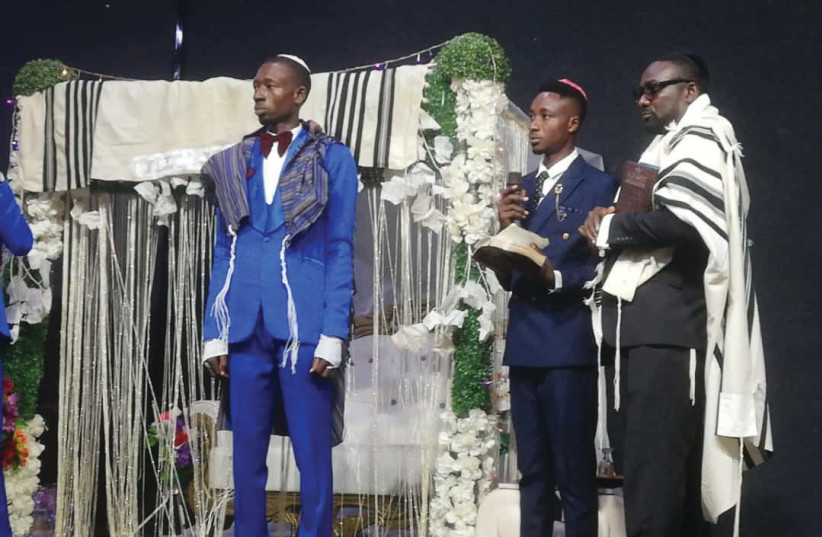

The Magazine spoke with Rochman during his latest trip to Africa, where he was filming episodes for his upcoming documentary We Were Never Lost. Speaking from the Ivory Coast, he discussed the content of the documentary:

“Historically the nation of Israel consisted of 12 tribes, however today the Jewish people primarily descend from the Kingdom of Judea, which only consisted of two-and-a-half tribes: Yehuda, Benjamin and Levi… while the rest of the tribes and the majority of Israel were displaced by the Assyrians and dispersed around the world prior to the Roman destruction of Jerusalem. This means if we found the descendants of the nine and a half tribes, we would be much more than the 15 million Jews we are today. This is not a myth. The question is where did they go?”

He continues about how he got involved in the project. “When I first found out there were Jews in Africa, I felt a sense of shock and the responsibility to connect with them. I asked myself: what if they had come to Israel first while we were still suffering in the Diaspora, wouldn’t we want them to come help and recognize us?”

This feeling led him to explore the topic in-depth, ultimately starting the documentary series with filmmakers Noam Leibman and David Benaym. “We started a documentary as a tool to shift the mindset and to help people learn who they really are.”

Rochman is currently filming Season One in Africa, with subsequent seasons planned to explore communities in Asia and South America.

THE IDEA of conversion is a salient point in the discussion of “if” and “how” these communities will integrate into the wider Jewish people. Rabbi Eliahu Birnbaum, also known as the Yehudi Olami – “the wandering Jew” – is a world-renowned expert in the field of Jewish communities throughout the globe: lost tribes, descendants of Jews and emerging communities. He is the director of the Straus-Amiel and Ohr Torah-Nidchei Yisrael Institutes, part of the Ohr Torah network of institutions.

Born in Uruguay, Birnbaum made aliyah 50 years ago. His career has included posts as the chief rabbi of Uruguay. He is currently serving as a dayan (rabbinical judge) at the Chief Rabbinate of Israel’s Conversion Court. It is in this capacity that he has an inside track on the world of the lost tribes.

Birnbaum’s work has brought him to over 140 countries. According to him, we should be focusing on three groups: nidchei yisrael (descendants of Israel); zera yisrael (a child or grandchild of a Jewish man); and giyorim (converts).

Many may be familiar with the term nidchei yisrael from the shmonei esrei (Amidah) daily prayer. In it, one of the 18 blessings is mikevetz nidchei Yisrael, or “gather in the dispersed of Israel.” According to Birnbaum, the view on this group has historically been that they have Jewish blood, but he points out that the thinking is flawed: “You can go anywhere in the world and find people with some Jewish blood, but that does not necessarily make them Jewish,” he says.

Rather, the term nidchei Yisrael refers to those with a spiritual connection to Judaism – in other words, spiritual descendants of the nation. To Birnbaum, this much is clear in their commitment to the Torah and mitzvot.

When Birnbaum approaches his work, he is coming from the angle of not “Who is a Jew?” but rather “What is the Jewish nation?”

“‘Who is a Jew?’ is a question for one person. We need to ask not a personal question but a general one. ‘What is the Jewish nation?’ More than anything, we have to introduce the question,” he stressed. In solving it, he believes we will see that these three groups are indeed our brothers and sisters.

Birnbaum is unique in his outlook in that as a dayan, his approach goes beyond ideology and is deeply rooted in practicality. “It is clear that the only way they can join the Jewish nation is through giyur [conversion to Judaism].” What this looks like is unique to the individual, as for many it is just “finishing the process” as they are already learned in Torah and mitzvot.

Birnbaum, like everyone else the Magazine spoke with, says the reason they want to join the Jewish people is not because they want to be considered Jewish when the Messiah comes (as the Sages forbade converts during this time) or to make aliyah – it is purely spiritual.

This concept is perplexing at first glance, though when explored, it makes sense. “We live in the post-modern world where people are looking for something… There are many Christians who move to Islam, so maybe it’s a rejection of Christian doctrine.” He also says, “They always say it is so hard to be a Jew, but how is it that so many want to become one?” Though he laments, “Maybe we are not ready to accept them… we haven’t opened our eyes to see something new.” He believes this is part of a “galut (exile) mentality” that has plagued us since the Holocaust.

Actions more than words

Rabbi Mordechai Yosef grew up in southern California with open-minded parents. This led him to explore different faiths, finally stumbling upon the Kabbalah Center in Los Angeles. After nearly a year of learning there, Yosef underwent an Orthodox conversion, and a year later came to Israel to learn in yeshiva, where he has been living for several years and received smicha (rabbinical ordination).

Yosef works with an organization called Pirchei Shoshanim, a group that works with the UN to develop university curricula about the lost tribes and their relationship with the African slave trade to America. In his work, he interacts with communities seeking to convert to Judaism. He views this as a century-old issue and one that needs a solution in our generation.

When working with these communities, he approaches it from a strictly halachic perspective. He tells of a ruling that the late Rabbi Chaim Kanievsky gave in which he said that Igbos, an ethnic group in Nigeria – who claim to be descendants of the tribe of Gad – have a connection, although they must still go through a form of conversion to end any doubt.

Dr. Ari Greenspan has visited almost every unique Jewish community in the world, from Africa to Asia to South America. Born to a US military rabbi, from a young age Greenspan was intrigued by Jewish tradition and communities. Having trained as a shochet (a person who carries out shechita (Jewish ritual slaughter), he joined Dr. Ari Zivotofsky at the age of 18 to assist these remote communities and train locals in the practice of shechita.

To Greenspan, the idea of whether or not these tribes are “lost” is totally irrelevant: “We can never know for certain if they are a tribe or not – it would be very hard to prove that they are. What is most astounding is the mass acceptance of Judaism. Not just that, but the intensity and spirituality of these communities. There are thousands of truly learned Jews… quoting the Midrash and the Sages… They are learning and reading at the highest levels.”

Throughout his travels around the world, Greenspan has dealt with every type of case – from those who claim to be descendants to those who converted, and those who have hidden their Judaism. From these encounters, he gained an insight into the unique customs held by each, all within the sphere of Jewish tradition.

One story he recounts was when he went to a village of crypto-Jews near Belmonte, Portugal. After slaughtering some sheep, he noticed that while the carcasses were hanging, the elders of the town made a small “x” on the back leg of the sheep. About a week later, after gaining their trust, Greenspan asked them about the mark. They said it was to indicate the spot for the removal of the sciatic nerve, a part of the animal that is forbidden for Jews to eat.

To Greenspan, the real questions relating to these communities are what is driving this mass adoption of Judaism, and why are they operating below the radar? In Africa, he points to missionary groups operating during the colonial period, who introduced them to the Torah and the Christian bible. As different groups evolved, many became messianic in nature, practicing like Jews but believing in Jesus. Many such groups still exist today, though there are those among them, particularly the younger members, whose practice is akin to that of Orthodox Jews.

He calls the phenomenon “YouTube Judaism” because the advent of the Internet allowed those in remote places to learn more traditional Jewish practices. Greenspan maintains that from a halachic perspective, none of them will be accepted by mainstream Judaism unless they have converted.

What conversion actually means is a different story. “There are two conversions: national and social. You can go through an Orthodox conversion but still be rejected by the masses because of the color of your skin or the way you look… It is something that happens even today.” What scares him is that “In 50 years, there could be millions of people who are shomer mitzvot and deal with antisemitism for being Jews, yet the State of Israel will never accept them… It is a very complicated and sad situation.”

The Igbos – descendants from Gad?

A community that figures prominently in debates over lost Jews is the Igbo community in Nigeria. Within a population of roughly 35 million, approximately 20,000 to 30,000 identify as Jews, the rest being Christians holding on to the idea of being Israelites. A number of genetic studies have been carried out on this community, some proving they are in fact descendants, while others show they are not.

Remy Ilona is a current PhD candidate at the University of California, Riverside, where his thesis in religious studies focuses on the Igbo community, genocide and antisemitism. A lawyer by profession, he has written 10 books discussing the Jewish origins of the Igbo people. To him, the connection is clear.

“The term ‘Igbo’ derives from Ivri, or ‘Hebrew’… For more than 500 years, scholars have been writing that Igbos are Israelites.” He says that Igbos have been victims of antisemitism and racism, most prominently in the Biafran War, where an estimated one to two million were killed at gunpoint or by starvation.

Ilona points to DNA studies that show lineage, as well as the many customs that Igbos practice that are similar to Judaism. “Jews and Igbos do not bury those who commit suicide, we both rest on Shabbat, just to name a few.” When asked about conversion, Ilona discusses omenana, the traditions and customs of the Igbo community, i.e. the traditional Igbo religion. It is this that he believes to be the source of the Torah and to which the Igbos should return.

Hakham Yehonatan Elazar-DeMota is a “Dominican-American-Sephardi Jew of Afro-Portuguese descent.” With a PhD in international law and a master’s in anthropology and religious studies, he has focused extensively on the idea of the lost tribes, particularly the Igbos. Elazar-DeMota first came to understand the Igbo story while at university and during conversations with Remy Ilona. He then dove deep to uncover the truth.

Elazar-DeMota established the Obadyah Alliance in 2016 to integrate those who claim Jewish ancestry. On the issue of Igbos, the Alliance issued a psak (halachic ruling) after five years of research – looking at claims and the legal aspects of these claims. The psak stated that Igbos are not Jews but rather Israelites, based on the finding of chazaka (presumption). The presumption is that 100% of Jews today cannot say with 100% certainty that they are 100% descendants of Jews. Consequently, the recommendation was not for Igbos to convert but to return to omenana, their own traditional religion.

Elazar-DeMota came to this conclusion for a number of reasons. First, he does not believe that full integration into the Jewish people is possible until a sanhedrin (rabbinical assembly) is established – and with this, prophets telling exactly who is a Jew and from which tribe. He also believes that before anything, Igbos must return to their roots. Whether omenana has a foundation in Torah therefore becomes less important, as it would let the Igbo people live within their ancestral homeland, Igboland (also known as Southeastern Nigeria), with their own traditional customs.

NATHANIEL SHMAYAH NWAMINI, an Igbo who lives in Nigeria and is fully Torah observant, disagrees with the arguments advanced by Ilona and Elazar-DeMota. He spoke about his experience and what he believes to be the path for the Igbo people.

Nwamini was born into a messianic family, although as he grew up, he, his mother and his brothers started to pull away from the group. Though tough at first – his father led the community – they began by learning about Shabbat and kashrut, taking on these mitzvot in the house. All the while, they were still attending the messianic synagogue, something he was not happy about. As time progressed, they completely separated from the messianic group and began to lead Torah-observant lives.

Nwamini, who currently works as an artist and creator of unique tallitot and kippot, explains how he was able to learn about Judaism and how to read and speak Hebrew. “The Internet has made everything so easy for everyone. I started to speak and read Hebrew in 2012, when my friend had a book about the language. Also, Kulanu [a Conservative group that helps educate African communities] gave our community books that I began to read. I started learning new mitzvot every Shabbat… It was not easy, but it was a process.”

Nwamini says that today in Igboland there are six synagogues with approximately 700 Torah-observant congregants. While discussing the potential origins of the Israelite story with Igbos, he acknowledges and even welcomes the fact that in order to eliminate any doubt about his community’s Jewishness, they must convert.

“I personally think it is very important… There are so many things attached to doing it. Most importantly, it avoids controversy and arguments about authenticity. Anyone can just claim they are Jewish if we [do not do giyur]. We are told to make fences around the Torah, and giyur is included in that.”

However, he laments that they are not given the opportunity to convert. “We believe that if it’s conversion, it has to be Orthodox and recognized by the Chief Rabbinate of Israel, but they are not letting us.”

Asked about the idea of omenana, he says he believes the idea is flawed, unacceptable and not in keeping with Torah observance. “Omenana is the native customs that our ancestors practiced, some of which are associated with Torah customs… but 90% is avoda zarah [idol worship].” He continues, “What is Torah? We say in Igbo culture that all the things our ancestors did is enshrined in the Torah, but it was abridged. And if we now have the original (the Torah), why not drop the abridged and take on the real?”

His devotion to the Torah is clear from the way he talks – with immense knowledge of Jewish sources and texts. “You can come to Igboland, and you can do Shabbat and eat fully kosher.” He continues, stressing the importance of Jewish practice over genetics, “Practicing goes first. No matter how much Igbos claim they are Israelites, those who are not practicing or are Christians shouldn’t be able to just come back… Why do people want to know who we are? Because we practice [Judaism].”

Nwamini’s wish is for acceptance into the broader Jewish world, as the current reality is harming the Igbos. “Jewish education in Nigeria is so lacking. We only have the opportunity to go to secular schools, and so when a child goes to these schools, he is not what he used to be when he left home.”

His wish is that the Rabbinate can look into their case on an individual level and allow them the opportunity to do giyur, study in Israeli yeshivot, and if they wish, make aliyah to join the Jewish people in Israel: “My message to the Rabbinate is ‘Even if you don’t accept our roots that we trace back to the Land of Israel, you should be able to accept the fact that we are observant and trying the best we can to be Jews without any rabbis or guidance. You should be able to accept that and come to our aid.’”

Something that has perplexed scholars about the Igbos and other African communities such as the Lembas in Zimbabwe are the customs they have. Many engage in traditional Jewish practices such as circumcision, niddah (martial purity laws) and ritual burial.

Greenspan, however, is not entirely convinced that these are indicators of descendancy from Hebrew tribes. A more reasonable assumption, according to him, is that the communities took on the Israelite story after hearing about missionaries who practice their customs. Missionaries are also pivotal in this story of the lost tribes, and even to this day are working hard to convert the emerging communities in Africa to Christianity.

Rochman and his team went to lengths to uncover the truth about the Igbo people, even finding themselves locked up in a Nigerian prison for 20 days after false accusations of espionage. He believes there is truth to the narrative that most Igbos hold, claiming to be descendants of the tribe of Gad.

Seeking to return

Crypto-Jews, also called Bnei Anasim or conversos, are Jews who have hidden their Judaism for centuries. These Jews were forced to practice underground following the Alhambra Decree, the law passed in 1492 that began the Spanish Inquisition and the mass expulsion of Jews from Spain. Faced with death or conversion, many began to practice underground. As time progressed, many kept their Jewish faith, although others assimilated into the nations.

With the arrival of tools allowing people to trace their ancestry, there is a growing number of people who felt Jewish, practiced the tradition and discovered that they are in fact Jewish.

Yaffah Batya deCosta is the CEO of Ezra L’Anousim, an organization that helps those who want to return to Judaism according to Halacha.

DeCosta explains that it is “almost like a convert except they are not really a convert. They are able to show evidence they are matrilineally descendants of Jews.” The process of individuals who prove this descendancy is called giyur lechumra, akin to a “return certificate” to Judaism.

DeCosta herself underwent such a process, having been born to a mother who hailed from the Azores, an island off the coast of Portugal. Because of this, she knows firsthand about the struggles crypto-Jews encounter when hoping to return to their roots. A big problem she brings to light is that of aliyah and how someone who undergoes this process can become eligible.

“In 1927, the Syrian community of Argentina instituted a takana [decree] that forbids converts or returnees from entering their community. This was adopted by the other communities as well,” she explains.

Though initially an internal problem, this has grown in the last decade after the Israeli government developed a policy stating that anyone who undergoes conversion must do so within a recognized Jewish community. “Because of the Syrian takana, returnees are unable to integrate into communities and therefore cannot go through conversion,” she laments.

DeCosta makes it clear that all those with whom her organization works are individuals who are already observant according to Halacha. They also have a familial connection. “You do not want a community that claims to be Jewish but is not actually Jewish,” she says.

Living life as Jews

All the experts stress to the Magazine the importance of individuals looking to integrate or claiming to be descendants as living fully Torah-observant lives. This means observing Shabbat, kashrut, Torah, holidays and everything else that comes with modern Judaism.

David Breakstone recently completed his term as deputy chair of the Jewish Agency executive, which capped off a 20-year career working extensively with emerging and isolated Jewish communities around the world. He holds that the most important aspect of the debate is “whether they are genuinely connected to Judaism today and living Jewish lives,” though he acknowledges the latter is a wide-open debate. He, like everyone consulted by the Magazine, stresses that they are not involved in pushing conversion at all, though he works to enhance the practices they may be engaged in, such as Shabbat and learning Torah.

Breakstone says that in conversations with community leaders, he stresses that in order to become authentically Jewish, they must undergo conversion. “Even descendants of conversos who can demonstrate some familial background for the most part need to go through a proper conversion.”

This may take the form of a reconnection ceremony, but typically this will be accompanied by concrete proof that they are descendants on their mother’s side. Either way, he says, “it is legitimate to be working with people who are celebrating Shabbat, learning Torah, involved with mitzvot, and are on a search to make their lives more fully Jewish… even if it’s clear they aren’t Halachicly Jewish but are on the path. As far as I am concerned, they are communities to be involved with.”

Moreover, Breakstone believes that the impact they can have on Israeli society and the Jewish world, if they make aliyah or convert, is immense: “More than 50% of those who are brought in from former Soviet Union countries are not Halachicly Jewish, though Israel hasn’t batted an eye about bringing them… No one is afraid they will contaminate the gene pool or change the Jewish character of the state.” He continues, “The ones I am working with are all committed to a Jewish lifestyle – and that can bring great value and diversity to the nation.”

The major sticking point, according to those the Magazine spoke with, is the idea of aliyah. Almost everyone interviewed says that the fear that millions of people who may not actually be Jewish will all of a sudden become eligible to immigrate to Israel is the single biggest factor holding back recognition of these communities. Of course, at first glance, this appears to be a major problem, though the responses show that it is not as serious as previously thought.

Greenspan stresses the fact that the reason these communities are practicing Judaism is not because they want to move to Israel en masse– most don’t want to. It is because of their sincere devotion to God. He is clear that in order for these communities to be accepted by the mainstream, each will have to undergo conversion. Rochman also says that of the small number that is practicing, an even smaller number want to move to Israel. In the case of DeCosta, many do in fact want to make aliyah – although it is abundantly clear through genealogy that they are in fact Jews, this has not changed the state’s mind about most of them.

One of the main reasons for this is discrimination. As the majority of these Jews are black, Asian or South American, they do not look like “typical Jews.” Of course, this can be easily explained by thousands of years of intermarriage and evolution, many having lived in different climates. Moreover, issues spill into Ashkenazi versus Sephardi culture, as most practice Sephardi traditions.

Economic competition is also a significant factor, as many of these “lost Jews” are in the upper echelons of their respective societies, working as doctors, lawyers and entrepreneurs. DeCosta puts it bluntly: “The bottom line is there are Jews who are preventing other Jews who are legitimately Jews from making aliyah.”

Where do we go from here?

So what is the next step? One group that could be used as a case study of how to deal with integration into the Jewish people is Bnei Menashe. The group comprises roughly 10,000 people hailing from India and Burma, all claiming to be descendants of the tribe of Menashe. Hillel Halkin is an author and translator who has dedicated much of the last few decades to uncovering the truth behind the 10 lost tribes, particularly Bnei Menashe. In his book Across the Sabbath River, he examines their claims to descend from Israelites.

Halkin shared his work with the tribe. “I visited a number of groups in western China, Thailand and elsewhere… but what I saw immediately [about Bnei Menashe] was that whether it is true or not, they were not like other communities… The body of evidence has too many detailed parallels between what they were practicing and that of biblical practices to put this down to coincidence.”

Halkin explains that throughout history, there has been a vast amount of literature on the lost tribes, though most are “literature of lunacy.” He says this, as practically all have been based on speculations that try to assemble relationships between customs and history in order to show a connection to the Torah. He adds that most are “superficial and can be brought to coincidence.”

He describes the two myths pertaining to Bnei Menashe, which are both false: “First is that it is a modern fabrication – it just isn’t true. The second is that for thousands of years you had descendants from the tribe of Menashe who were practicing until modern times.” To Halkin, the most likely answer to their customs is that their ancient religion had attributes similar to those found in the Torah, and when the British conquered and missionized the area, the familiarity with the stories and traditions led people to take on the lost tribe claim. In short, it probably all came from the spread of Christianity.

It was not until Rabbi Eliyahu Avichail embraced the community and learned with them that their integration began. Since the members of Bnei Menashe were not considered Halachicly Jewish, the only way toward integration and aliyah was through conversion. As a result, Avichail, with the blessing of the Rabbinate and the Ministry of the Interior, started to bring individuals to undergo giyur and become Jews.

This process continues, with work being done by an organization called Shavei Israel, led by Michael Freund. The steps are as follows:

- The group is identified as one that is seriously committed to Judaism.

- Rabbis from the Chief Rabbinate go to the group and interview them one by one to determine whether they are sincere in their conviction to convert to Judaism.

- Those individuals are granted visas by the Ministry of the Interior and come to Israel, where they undergo formal conversion.

- Following the giyur process, they are considered Halachicly Jewish by all mainstream organizations and the Rabbinate.

The success of the integration has been vast, as today members of Bnei Menashe are fully integrated Israeli Jews, some even marrying outside of their community. Though it may be seen as overreaching by some other groups around the world, it is ultimately through this process that the most sense is found. However, as stressed by all with whom the Magazine spoke, the foundation of any process must include living a Torah-centered life.

WITH THIS in mind, as Birnbaum says, it is clear “we cannot just close our eyes” to their communities forever, and a plan must be formulated for the future. According to those who have dedicated their lives to this mission, the most logical short-term plan is to establish a committee of sorts to outline recommendations. As the State of Israel is the de facto representative of world Jewry, it makes sense that this forum would be in the Knesset and involve experts from around the world, as well as lay leaders from these communities.

Interviews and subsequent analyses of the facts would determine the best way forward. Nearly everyone is in agreement that there can be no “cookie cutter” approach, as each community has its own story. That said, conversion must still take place on an individual, not a community level, as maintaining millennia-old traditions is something all agree on.

For all those consulted, the Torah and maintaining tradition are at the forefront of their work. Almost every single one is a rabbi by training or has deep knowledge and respect for the Jewish tradition. This enables them to pick up on the nuances that may escape secular researchers when studying these communities, as has been the case in the past.

Greenspan refers back to the story of the sheep, where only someone trained in ritual slaughter would pick up on the marking. Rabbi Mordechai says that “everything I do is with the guidance of my rabbis.” Rochman says that the people against this work are usually “anti-Torah” and that “the reality of our work is to unite… to create a reality that doesn’t exclude other people. Some people live in a zero-sum reality, where it hurts if something helps anyone other than themselves.”

He also stresses the responsibility we have as a people. “It’s also Jews who refuse to take responsibility. I grew up knowing our future is in our hands. Unfortunately, there are those that believe it is not our right, and we have to ask the world for the right.”

Moreover, their work simply seeks to improve the future of all our people and enhance our culture. DeCosta notes that “the people who want to build the Negev (verse 20 in Ovadia states ‘the exile of Jerusalem which is in Sepharad shall inherit the cities of the southland’)… and they are sincere – I went to the beit din [rabbinical court] three times. I would have gone 100 times if I needed.”

Greenspan says, “Judaism is so colorful, it is like a tapestry… with threads going every direction. We should retain this tapestry.” Rochman hopes his work can empower the next generation to be stronger in standing up for who we are as people, shift public perception, and spark a conversation about whether “our values and Torah are fundamental to our society.” Rabbi Mordechai speaks poignantly about how this work can “emphasize to the world the diversity of the Jewish people and can help to combat antisemitism.”

It is certain that these activists are not extremists or hoping to cause any harm. In short, they are a small but dedicated group working simultaneously to better the future of the Jewish people, both in the Land of Israel and in the Diaspora. By opening minds to what may seem foreign, they are educating Jews and non-Jews alike about who the Jewish people really are and are writing future chapters in our people’s story.

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });