How real is the Saudi-Iranian thaw? - opinion

Saudi leaders no doubt believe that restoring diplomatic relations is a useful political ploy, but surely appreciate that the deal is superficial.

Saudi Arabia and Iran have been rivals for religious and political power ever since Iran’s Islamic revolution in 1979. Their antagonism is a visible expression of the deep chasm that divides Islam into its two main branches, Sunni and Shia.

The extremists of each side regard the other as apostates, heretics and infidels. Even so, arms-length diplomatic relations were maintained, with a short hiatus between 1987 and 1990 instigated by Saudi Arabia, but they were decisively severed by Iran on January 2, 2016, and remained so for seven years.

A fact rarely mentioned is that Saudi Arabia, the very epicenter of the Sunni Muslim branch of Islam, is home to more than two million Shia Muslims. This large minority – estimated at between 10% to 15% of the total population – lives largely in the Eastern Province in the Qatif and al-Ahsa governorates.

Saudi Arabia’s Shia minority, whose members frequently complained of being treated as second-class citizens, found a champion in the early 2000s in Sheikh Nimr Bagir al-Nimr, a Shia cleric. In 2009 he began demanding that the government respect Saudi Shia rights. He backed this by threatening to split the oil-rich Qatif and al-Ahsa regions from Saudi Arabia and unite them with Shia-majority Bahrain.

Saudi authorities responded by arresting al-Nimr and 35 others. Two years later, in 2011, Nimr took a leading role in the Arab Spring uprising in Saudi Arabia. Saudi police again arrested him during what they described as an “exchange of gunfire.” On October 15, 2014, he faced Saudi Arabia’s Specialized Criminal Court and was sentenced to death. On news of Nimr’s execution along with 46 others on January 2, 2016, Iran severed diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia.

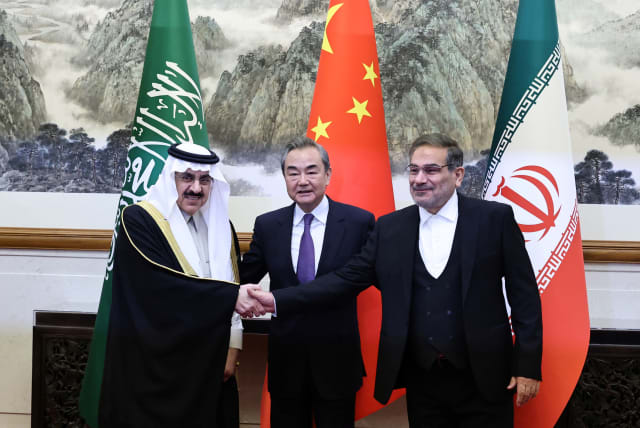

Recently, to the surprise of many, China stepped forward as an honest broker, and its good offices resulted in an agreement between the long-standing adversaries. Last month, Saudi Arabia and Iran agreed to renew diplomatic relations and refrain from interfering in each other’s domestic affairs. April 6 saw the foreign ministers of Iran and Saudi Arabia meeting in Beijing for the first formal gathering of their top diplomats in more than seven years.

HOW TRUE, deep and lasting can this reconciliation be?

The immediate prospects are not bright. In Yemen, even after the agreement, the Iran-backed Houthi rebels mounted an attack in the oil-rich Marib province. Worse, 10 days after the Saudi-Iran agreement, the Houthis unleashed a barrage of drone and missile attacks on Saudi Arabia, targeting a liquefied natural gas plant, water desalination plant, oil facility and power station. Over the past few years the Houthis have fired hundreds of missiles into the heart of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia’s capital.

The problem that Iran poses to the civilized world stems entirely from the Islamic revolutionary regime that the nation wished on itself back in 1979. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini became supreme leader in December 1979. His philosophy, which he set out nearly 40 years before, required the immediate imposition of strict Sharia law domestically, and a foreign policy aimed at spreading the Shi’ite interpretation of Islam across the globe by whatever means were deemed expedient.

“We shall export our revolution to the whole world,” he declared. “Until the cry ‘There is no god but Allah’ resounds over the whole world, there will be struggle.”

Pursuit of this fundamental objective has involved the state – acting either directly or through proxy militant bodies – in a succession of bombings, rocket attacks, assassinations and acts of terrorism directed not only against Western targets, but against non-Shia Muslims as well.

“To kill the infidels,” declared Khomeini, “is one of the noblest missions Allah has reserved for mankind.”

With Islam’s two holiest cities, Mecca and Medina, within its borders, the Saudi kingdom sees itself as the leader of the Muslim world – a claim hotly contested by Iran. In 1987, when tensions reached breaking point during the Hajj, Khomeini declared that Mecca was in the hands of “a band of heretics.”

Now, in restoring diplomatic relations with Sunni leaders whom they regard as heretics, Iran’s leadership may be making a pragmatic political move. It is scarcely likely to represent a sincere beating of swords into plowshares.

In his extensive writings on Islamic philosophy, law and ethics, Khomeini affirmed repeatedly that the foundation stone of his ideology, the very objective of his revolution, was to impose Shia Islam on the whole world.

“We wish to cause the corrupt roots of Zionism, capitalism and communism to wither throughout the world,” he declared. “We wish, as does God almighty, to destroy the systems which are based on these three foundations, and to promote the Islamic order of the Prophet.”

One wonders whether Communist China has noted that it is explicitly included among the targeted enemies of Iran’s Islamic revolution, that it has been pinpointed by the regime for destruction? China may yet find its new ally biting the hand that feeds it.

Iran’s leaders want to destroy the world as we know it. They want to overthrow Western-style democracy, of which America is the prime exponent, to wipe out the State of Israel, to eliminate communism, to impose Shia Islam first on the Muslim world, and then on the world entire, and to achieve political dominance in the Middle East.

They believe that any means are justified in the struggle to achieve their aims – God-given aims, as they perceive them. In pursuing them they are prepared to bluff, trick and cheat, and to undertake or facilitate acts of terrorism regardless of the deaths or injuries inflicted.

For 44 years world leaders have been unable, or perhaps unwilling, to recognize the quintessential purposes that motivated the leader of Iran’s Islamic revolution of 1979, or to appreciate that these same objectives have driven the regime ever since and continue to do so.

Saudi leaders no doubt believe that restoring diplomatic relations is a useful political ploy, but surely appreciate that the deal is superficial and cannot begin to touch the real problems that the Iranian regime poses to the Saudi kingdom and the rest of the world.

The Sunni Arab world recognized some time ago who its main enemy was. The Abraham Accords are one outcome. Saudi Arabia is widely perceived as on the brink of joining the association. Would its new reconciliation with Iran withstand the shock?

The writer is the Middle East correspondent for Eurasia Review. His latest book is Trump and the Holy Land: 2016-2020. Follow him at: www.a-mid-east-journal.blogspot.com.

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });