Israel isn't suffering a constitutional crisis, but an identity crisis - opinion

As we stand in 2023, a clear, unified vision for Israel’s Jewish inhabitants has yet to emerge. Instead, the existing government has given rise to two sharply contrasting visions

We stand witness today to an escalating identity crisis in Israel, one that threatens to cascade into a full-fledged constitutional dilemma. This crisis transcends the realms of mere political turbulence or potential judicial transformations. It dives deep into the ideological heart of the nation, reflecting a divide between two considerable Jewish factions with divergent visions of what Israel should be.

On one side of this ideological divide, we find the state camp, comprising those who interpret the creation of Israel as the culmination of the Zionist dream. They believe in a democratic, Jewish-liberal state that symbolizes the realization of this dream.

In sharp contrast, the other camp is made up of religious traditionalists who assert the primacy of Torah law over civil law. This faction strives for a conservative Israeli society that is more deeply steeped in religious values. This ideological divergence isn’t new. It has its roots in Israel’s inception in 1948, but it has become more pronounced over the last decade due to demographic shifts and the development of distinct political blocs.

An increasingly unbridgeable gap in Israeli politics

Between these two camps, liberal and conservative Israel, there yawns a widening chasm that seems increasingly unbridgeable. This divide is further intensified by a discourse laden with misinformation, offensive remarks, and the casual, often destructive use of rhetoric. Such a dialogue not only poses a risk to Israel’s international reputation, potentially affecting its rapport with powerful allies such as the US, but it also inflames a potentially insurmountable internal rift within the Jewish population itself.

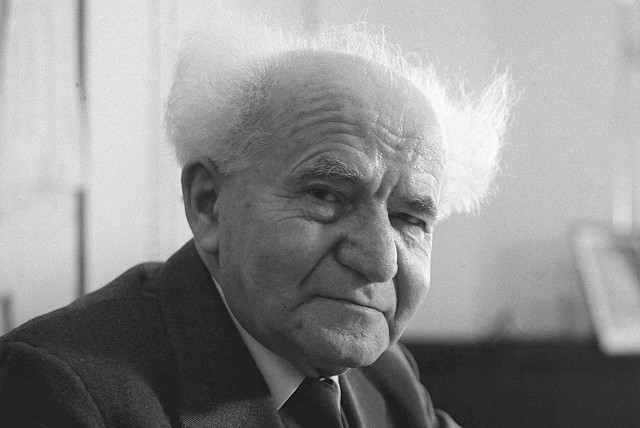

Cast your mind back to 1948, when the dream of an independent Jewish state was brought to life. It happened when various Jewish ideologies coalesced around the shared goal of national self-determination. David Ben-Gurion, a leading advocate of this cause, managed to unite these diverse strands of thought, if only temporarily, and forge a path toward realizing the vision. However, this union didn’t manage to dispel deep-rooted disagreements about the structure and identity of Jewish society.

NOW, AS we stand in 2023, a clear, unified vision for Israel’s Jewish inhabitants has yet to emerge. Instead, the existing government has given rise to two sharply contrasting visions. This dichotomy has triggered an ideological civil war, pitting religion against democracy.

On one side, we see a conservative interpretation of Judaism, sometimes verging on the messianic. On the other, a democratic, secular state – a concept championed by both Ben-Gurion and Ze’ev Jabotinsky, calling for a clear distinction between religion and state.

Representatives of religious Zionism within the current government, far from satisfied with the existing arrangement, desire a more profound transformation. They envision a state that is governed by religious Jewish principles. The zeal of this aspiration is reflected in their recent legislative proposals.

Even if these proposals fail to make it through the legislative process, they clearly articulate a bold new vision for a religious Jewish state. This fervor has even led some to label those they deem insufficiently devout as “non-Jewish,” even if these individuals have a matrilineal Jewish heritage according to religious law.

Counteracting this vision, we find the state-owned camp. This group includes liberals, conservatives, religious, and secular individuals alike. Their shared vision revolves around a desire for a clear separation of powers, appropriate checks and balances among authorities, and a resistance to legislation that would enshrine the tyranny of a parliamentary majority.

They envisage a liberal, democratic Jewish state in line with the spirit of the Declaration of Independence, embodying the ideals of Ben-Gurion and Jabotinsky. Their vision stands in stark contrast to that of their counterparts.

The emergence of this ideological divide can be attributed to three interconnected factors. First, demographic and sociological changes have inclined the majority of Israelis toward more religious and right-wing parties. Secondly, a number of elected officials, anticipating a persistently right-leaning political landscape in future elections, have been inspired to initiate legislation. Finally, the lack of immediate existential security threats has created an opportunity for domestic reform.

Regardless of the fate of the proposed legislation, the identity divide is undeniable and its effects increasingly potent. No existing leader seems capable of – or perhaps interested in – reconciling these varied groups: Orthodox, hard/soft religious sects, traditionalists, and secularists.

Moreover, this internal strife often overlooks the perspective of the non-Jewish minority, constituting approximately 20% of the population, in the broader identity narrative. In this context, talk of unity comes across as mere lip service, a placating rhetoric to stave off public disillusionment.

For those willing to confront the situation realistically, the picture is abundantly clear. The two camps are distinctly differentiated and resolutely entrenched. It seems an ideological separation is imminent. It would, however, be in the best interests of all parties if this were achieved amicably and without violence.

The writer is the chair of the Middle East and Political Science Department at Ariel University.