How Jerusalem's archaeology was changed by a German cuckoo clock mechanic

Schick’s legacy in Jerusalem is enormous. Few people have had such an impact on the face of one of the world’s most famous cities.

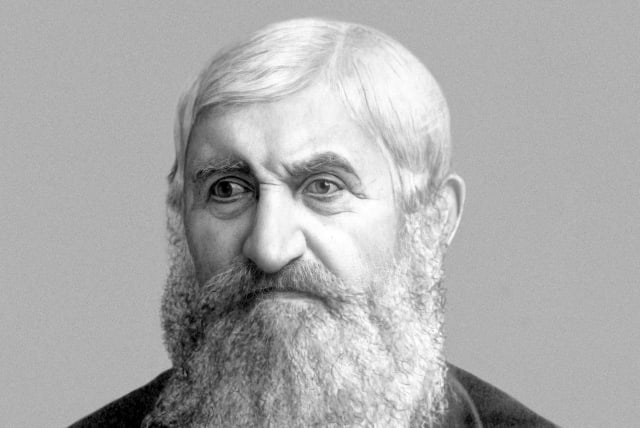

In my humble opinion, it behooves Jerusalem to honor Conrad Schick (1822-1901), the German-born polymath and autodidact architect, cartographer and archaeologist who did so much to develop the holy city in the late Ottoman period and became a towering ecumenical figure as Jerusalem lurched toward modernity.

Ideally, a memorial for him would face Tabor House (Beit Tavor) at 58 Hanevi’im (Prophets) Street – the family mansion the Protestant missionary built in 1882 – which has housed the Swedish Theological Institute since 1951. While the homestead takes its name from Psalm 89:12, like so much of Schick’s life it is idiosyncratic, alluding both to a family camping trip to the Galilee and the site of Jesus’s transfiguration.

His multifaceted career – as rich as he was personally parsimonious – was the subject of the recent (Feb. 6-7) “Conrad Schick and His World” academic conference, hosted by Jerusalem’s Albright Institute of Archaeology and Paulus-Haus, in conjunction with the University of Haifa and its Zinman Institute of Archaeology; Kinneret College and its Zev Vilnay Chair for the Study of the Knowledge of the Land of Israel and its Archaeology; the German Association for the Holy Land (DVHL); and the German Protestant Institute of Archaeology in the Holy Land (DEI). The conference attracted scores of scholars from Israel, Jordan, Britain, the United States, Germany and Denmark, and many more who followed the proceedings on Zoom.

What is the legacy of Conrad Schick?

“I discovered Conrad Schick’s materials in the archives [of the Palestine Exploration Fund in London] when I worked on the archaeology of the Temple Mount, and I was immediately impressed by their value for studying ancient Jerusalem,” said University of Haifa archaeologist David Gurevich, who organized and chaired the symposium. “Because key sites such as the underground passages below the Temple Mount, the site of the Antonia Fortress, or the Northern Aqueduct and the Pool of Hezekiah are inaccessible today for investigations, we must extract information from the 19th-century works. Schick’s unpublished plans and reports constitute a vital source of data in my research.

“Then, I heard from colleagues worldwide that they also employ Schick’s materials to study other sites in Jerusalem. I decided to launch a conference which will bring us all together to discuss and evaluate Schick’s works. This was a venue for the leading experts for two days of intensive brainstorming. New insights were developed, and I am working to bring the papers to press as a book so these would be available to wider audiences. It is incredible that 122 years after Schick left this world, we are still discovering Jerusalem through him.”

Düsseldorf-born Israeli tour guide Shirley Graetz explained how Schick came to be beloved by Jerusalem’s Jewish, Christian and Muslim residents, their Turkish masters, and European visitors. His friends included British major-general Charles “Chinese” Gordon (1833-1885); Ottoman government official Yusuf Effendi al-Khalidi (1842-1906); and Rabbi Meir Auerbach (1815–1878), the Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Jerusalem, who in 1874 commissioned Schick to draw up the blueprint for Mea She’arim.

Born in the village of Bitz in what was then the Kingdom of Württemberg and today belongs to the German federal state of Baden-Württemberg, Schick studied theology in Basel, Switzerland. Sent to Jerusalem in 1846 by the St. Chrischona Pilgrim Mission based in Bettingen near Basel, the missionary quickly realized that the denizens of the impoverished Ottoman backwater needed medical care and employment more than replacement theology or the cuckoo clocks and wood carvings Schick was selling. That understanding and the financial difficulties faced by the St. Chrischona Pilgrim Mission led Schick to work in the missionary enterprises of the Anglo-Lutheran Joint Bishopric of Jerusalem, headed by Bishop Samuel Gobat. And so the German turned his carpentry skills to teach in the House of Industry run by the London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews, often called the London Jews’ Society (LJS).

Headquartered at the Anglican Christ Church inside the Jaffa Gate, it was the first Protestant church in the Middle East. The LJS’s House of Industry was located in a separate building near the Damascus Gate, which the locals still refer to as Dar Schick (Schick House). There the thrifty Swabian with his Protestant work ethic promoted the concept that people should earn a living from their work rather than depend on charity. Schick’s carpentry skills and intuition led him to establish an entire industry producing olive wood tchotchkes for the burgeoning souvenir trade, explained Jerusalem antiquarian Lenny Wolfe. That woodworking enterprise, in turn, led to Schick creating elaborate scale models. Arguably, the most notable was the meticulous 3x4-meter model of the Haram a-Sharif/Temple Mount he crafted for the Ottoman Pavilion at the 1873 Vienna World’s Fair. Ironically, it fell into oblivion almost immediately after its proverbial 15 minutes of fame.

Relying on his firman (royal mandate) as official modeler for Sultan Abdulaziz Han bin Mahmud (1830-1876), as well as his charm, the pioneering explorer conducted research on the Haram a-Sharif and its underground passages, cisterns and tunnels – which were off limits to other Western scholars. (In 1867, lieutenant – subsequently promoted to general and then Sir – Charles Warren of the British Royal Engineering Corps and the Palestine Exploration Fund managed to dig shafts around the Temple Mount.)

Based on Warren’s probes, Wilson’s digs as head of the 1864-65 Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem which produced the first precise map of the Temple Mount and its cisterns and passages, and Schick’s own research which extended that information and discovered a few “new” cisterns, the German explorer constructed an elaborate 1:200 scale model with dozens of movable parts revealing previously unknown underground areas of Mount Moriah. His masterpiece remains a unique source about subterranean Jerusalem and its sacred precinct.

The inveterate model maker displayed two models for sale at the Vienna expo in the summer of 1873. Schick’s patron King Charles I of Württemberg preferred the model of the biblical Tabernacle and Ark of the Covenant.

Prior to arriving at the Vienna fair, the detailed replica had already toured Britain and Europe, and had been admired by several crowned heads of state. So delighted was His Majesty with his purchase, that he raised Schick to the rank of Royal Württembergian Hofbaurat (Privy Construction Councilor) – the equivalent of knighthood.

But what happened to Schick’s Temple Mount model?

After the Vienna exhibition, the German tried to sell his unique creation. Eventually, his agent Rev. J.H. Brühl unloaded it at the Chrischona Mission House outside Basel, where the model was secreted away for 138 years before being bought in 2011 by Jerusalem’s Christ Church and brought the following year to its permanent home just inside the Jaffa Gate.

Plans call for the fragile model to be complemented by a film showing the exhibit’s sections being raised and lowered to reveal the Temple Mount’s hidden recesses. Today, the model is explained by a few photos in a cycled PowerPoint presentation. Its return to Christ Church and its spiritual home closes a circle, demonstrating that while Schick the missionary enjoyed meager success in gaining converts, his scientific legacy was enormous, said Rev. David Pileggi of Christ Church, who co-authored a paper at the conference.

Conference participants also viewed Schick’s models of ancient Jerusalem on display in the museum in the basement of Paulus-Haus on Nablus Road. Among them is his striking model of the Temple Mount in various periods. The structures depicting different eras can be set or removed, replacing the earlier buildings as “playing Lego.” Alas, in the 1950s, Schick’s models of the Tabernacle and the Haram a-Sharif were deaccessioned by the Harvard Semitic Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and subsequently lost.

Beginning in 1872, Schick became a prolific contributor to the Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement and its German-language scholarly equivalent, Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins (ZDPV – Journal of the German Palestinian Society). In 1887, he authored the magisterial Beit el Makdas, oder, der alter Tempelplatz zu Jerusalem (Beit el Makdas refers to the ancient Temple of Jerusalem), a book that elaborated his work on the Temple Mount.

Gurevich explained that Schick’s reports with their patchy English and odd spelling were often rephrased by the editors of the PEF’s journal in London before being published. An editor could inadvertently introduce myriad errors in his interpretation of Schick’s ambiguous letters. While many of his papers remain unpublished, “the PEF published about 220 of his papers, most of them on Jerusalem, which is a phenomenal achievement for any scholar,” noted Gurevich.

Schick became caught up in the imperial rivalry over the Sick Man on the Bosporus. European scholars in Jerusalem placed a nationalist spin on archaeology and history, even as they sought to plunder Middle Eastern antiquities to display in the British Museum in London, the Louvre in Paris, and the Altes Museum in Berlin. Moreover, said Joel Stokes of University College in London, Schick was maligned as unreliable by the British because of their anti-German bias and xenophobia.

Ran Bar Yaakov of the University of Haifa recounted how the self-taught Schick disputed other scholars’ view that Jesus entered Jerusalem on Palm Sunday through the Hulda Gate. The Christian messiah came through the Golden Gate, and it was here in 626 that the Byzantine emperor Heraclius – who reigned from 610 to 641 – led the triumphal return of the True Cross which the Persians had captured in 614. Bar Yaakov showed the line of sacred geometry linking the Church of the Ascension on the Mount of Olives with the Church of the Holy Sepulcher passing through the Golden Gate.

Without the benefit of today’s ground-penetrating radar, many of Schick’s interpretations about ancient ruins have been proven to be correct by subsequent research. His contributions to the archaeology of Jerusalem are fundamental to modern scholarship. In particular, Schick will be forever remembered for the discovery of the Siloam Inscription in Hezekiah’s Tunnel in 1880, and the excavations he conducted at the Muristan in 1893 in search of the city’s Second Wall, which proved that the Roman execution grounds at Golgotha were extramural.

Schick’s legacy in Jerusalem is enormous. Anyone familiar with the city center knows the handsome buildings he designed, such as the Hansen House leper colony in Talbiyeh; the Talitha Kumi girls’ school on King George Street – part of the façade of which is preserved as a local landmark; and the New Gate to the Old City.

Few people have had such an impact on the face of one of the world’s most famous cities. Safra Square has a memorial wall dedicated to Schick, and the lane leading from Nablus Road to the Garden Tomb is named after him – and misspelled. But on reflection, the German polymath deserves more. The barren piazza in front of the Hadassah Academic College on Hanevi’im Street should be named Conrad Schick Platz in his memory. ■

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });