Yom Kippur War: Newly released archives detail Israel's POW deal with Syria

As part of its collection marking fifty years since the Yom Kippur War, the National Archives of Israel has detailed the role of US Sec. of State Henry Kissinger in the Israel-Syria negotiations.

As part of its collection marking fifty years since the Yom Kippur War, the National Archives of Israel has released new documents detailing US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger's role in delivering a list of Israeli prisoners of war held by Syria. This move helped pave the way for a prisoner exchange and troop disengagement in the northern theater.

Despite the signing of a ceasefire on October 24, 1973, IDF troops remained in Egyptian and Syrian territory thanks to the gains made after the surprise attack by the Arab nations on Saturday, October 6, 1973 - Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar.

An economic crisis due to the continued mobilization and rearmament of Israeli troops contributed to Prime Minister Golda Meir's headache as her government grappled with domestic and foreign policy issues.

In October of 1973, Israel and Egypt began discussions surrounding a prisoner-of-war exchange, and the withdrawal of Israeli troops and exchanges were carried out in November before a disengagement agreement was signed in January 1974.

Enter US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. Kissinger was determined to play a prominent role in the next round of negotiations between Israel and its enemies, in part a bid to keep in check the Soviet Union's relationship with the Arab nations.

Dealing with the Syrians proved to be a more difficult task. Syria, under the leadership of President Hafez al-Assad, was determined for Israel to withdraw beyond the Purple Line, the ceasefire line between the two countries after the Six Day War of 1967. It refused, however, to present Israel with a list of prisoners it had captured or to allow Red Cross representatives to visit them.

Kissinger was informed by Israel that no withdrawal discussions could take place unless a prisoner list was handed over, accompanied by Red Cross visits.

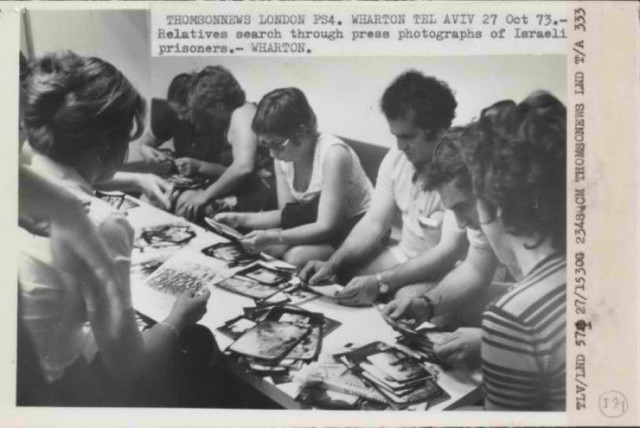

After the deal with Egypt was struck, there were still 131 Israelis missing from the Syrian Front, considered prisoners of war.

Israel's past prisoner exchanges with neighboring nations show history repeats itself

Images and videos circulating in Arab media led to a gloomy and angry reaction among the Israeli public, and Israel eventually lodged a complaint with the UN about the prisoners' treatment. Meir's government informed the Syrians, through the US and the Red Cross, that it would be willing to allow 15,000 residents of the Syrian Golan Heights and to transfer captured Syrian positions during the War to the UN, all in exchange for the return of the prisoners.

Israel's Foreign Ministry, which was responsible for maintaining contacts at the time with the Red Cross, understood how the prisoners were being used as bargaining chips by the Syrians. A foreign ministry official, Mordechai Kidron, wrote that the Syrians knew the value of holding on to the Israelis.

In December 1973, Kissinger organized the Geneva Peace Conference, which Israel was reluctant to attend until the prisoner issue with Syria was sorted out. On December 16, Meir stated that Israel would not participate unless a list were presented by the Syrians. The Syrians' refusal to attend led to rumors that all the prisoners had been killed, leading to further protests in Israel.

By January of 1974, as Meir's government was attempting to conclude its agreement with Egypt, Kissinger was shuttling between Israel and Cairo as part of his role in the negotiations. Released archives show that on January 13, Israel's Deputy Prime Minister Yigal Allon conveyed that Kissinger was also traveling to Damascus, as it had been hinted that the Syrians could be willing to negotiate. Allon argued that Israel should push Kissinger to tell the Syrians Israel was willing to discuss a withdrawal provided a prisoner list was handed over and Red Cross visits were guaranteed.

Israel also hoped to stabilize the shaky ceasefire, in place since October, but which the Syrians had repeatedly broken. Military positions on the Israeli Golan Heights were consistently shelled, as were civilian settlements.

On January 20, Kissinger flew to Damascus to meet with Assad, who claimed that the Israeli prisoners' conditions were good and that if Israel wanted a deal, there must be a significant withdrawal of Israeli forces from the Golan Heights. Kissinger knew that the Israelis would reject such a deal but decided to present it as an opening gambit in negotiations.

Released archival documents show that Egypt's President Anwar El-Sadat sent a message to Golda Meir regarding the importance of a deal between Israel and Syria. Israel suspected this was part of US pressure to help lift the Arab nations' oil embargo on the United States, which was causing domestic disruption. Meir responded to Sadat that the prisoners' plight was still the main focus and a major stumbling block preventing Israel from even considering the Syrians' demands.

Despite the diplomatic game of ping-pong that ensued, by February 3, Meir informed the Israeli government that Kissinger had proposed that Israel would suggest a new demarcation line between Israel and Syria once Kissinger had a prisoner list in his possession. It was decided to inform Kissinger that the government would be authorized to present a territorial solution only after he had received the list and Red Cross visits were guaranteed.

On February 5, Kissinger proposed to Assad that, initially, Syria would provide the number of prisoners before a list of names was transferred to the Syrian Embassy in Washington, DC. After the Red Cross had visited, Israel would propose a withdrawal solution. Kissinger was also attempting to relieve the oil embargo after the Saudis informed him that Syria was maintaining the embargo to pressure the Israelis.

US pressure, along with that of Saudi Arabia and Egypt, on Assad compelled him to agree to hand over the list of prisoners' names. On February 7, 1974, Kissinger received a message from the Syrians that they were holding some 65 POWs, and the message was passed on to Meir in Jerusalem.

Following a few weeks of internal anxiety within Israel about the outcome, Arab leaders, including Sadat and Assad, met at a summit, and on February 19, 1974, the foreign minister of Saudi Arabia and Egypt arrived in Washington with the prisoner list and handed it over in a sealed envelope to Kissinger.

They promised to lift the oil embargo within two weeks, and one week later, Kissinger again met with Assad, who guaranteed Red Cross visits and approved Kissinger handing the list over to the Israelis.

Relief ultimately arrived for the Israelis on February 27, when Kissinger handed over the list of prisoners' names. Finally, on March 1, 1974, exactly 50 years ago on Friday, the Red Cross was allowed to visit the Israeli prisoners of war. Although it may seem somewhat insignificant in the grand scheme of war, the exchange of the prisoner list was a major factor in the moving forward of the Israel-Syria ceasefire. However, fifty years later, the two nations remain officially at war.

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });