Drawing, surely, is one of the more clearly definable areas of the visual arts. Or is it?

One would have thought there are a couple of logistical criteria that are universally recognized, such as the horizontal and vertical confines of the pictures. Works in the discipline are almost invariably two-dimensional without, for example, the densely layered structure often found in oil paintings. They also, generally, stick to their physical parameters. But should you go to the Jerusalem Artists’ House to view the current showing, you might have yourself a little rethink.

The exhibition is an expansive and highly variegated affair, with dozens of works covering large areas of the walls of all three floors of the statuesque, 19th-century edifice. It is also the centerpiece of the eighth edition of Traces VIII – Biennale for Drawing in Israel, which takes in additional layouts at a string of other venues around Jerusalem, including Ticho House, Jerusalem Print Workshop, Barbur Gallery, Koresh 14 Gallery and HaMiffal.

The event began life in 2001 and is presented as “a comprehensive, unique artistic enterprise, an ongoing celebration of the medium of drawing and its many and diverse manifestations.” Having surveyed the spread at the Biennale hub, on Shmuel Hanagid Street, I can vouch for the reference to the eclectic mindset.

What is on display at Israel's 8th Biennale for Drawing?

The Traces VIII rollout goes by the name “More than One” and reflects the flexible approach to the discipline adopted by chief curator Irit Hadar. The drawing sets in the main exhibition pertain to two principal formats: series and clusters. The former indicates an ongoing narrative and a thematic thread that comes across in many of the exhibits, as exemplified in the extensive creation by Hila Spitzer, which greets you as you make it to the top floor.

Getting close to Spitzer’s The Way to the Swimming Pool – the title spells out the continuum pictorial lay of the land – you get the idea that there is more to drawing than initially meets the eye and brain. The storyline of the work is simple and in plain view. The serial spread takes in no less than 58 pictures, made with crayons and gouache, and they illustrate – literally – the route Spitzer takes from home to the neighborhood pool.

It is fun to follow the snapshots, imagining what she sees as she traverses her regular route. It is as close to a corporeal reenactment of the experience as a two-dimensional manifestation can be.

The artist decides how many junctures along the way are noteworthy, or important to the tale she is spinning, but we do get a pretty palpable impression of the phenomena she encounters en route. This appears to be taking drawing a step further into largely uncharted dimensional waters.

That borders on realism, and there is a similarly verisimilitudinous element to Yoav Weinfeld’s slot in the exhibition, on the intermediate floor. As illustrative appellations go, Urinating in the Dark is as graphically descriptive and – possibly – individually familiar as they come. Without getting too personal, it is probably fair to say that some of us may, say after imbibing copious quantities of beer around a campfire, have experienced the trying shenanigans of extricating ourselves from our tent and stumbling through pesky undergrowth, in extremis, to eventually achieve blissful relief.

Weinfeld’s darkly humorous work is unambiguous and subtle in equal parts. The linear components of the monochrome set impart the unmistakable impression of wall tiling grouting, of the kind to be found in restrooms the world over. And, just in case the observer has any doubts about the experiential plot, there is a head-and-shoulders segment of a humanoid character bearing a facial expression that could be construed as a mixture of anguish and epiphany.

Humor, albeit with serious existential undertones, also comes through in Karen Dolev’s Little Trees. The moniker implies something quaint and fundamentally adorable, but observe the carpet swatch-like arrangement for a minute, and the central, repetitive, motif comes into focus.

What looks, at first glance, like a pretty arboreal figure may, possibly, remind one of the recent festive slot in the Christian calendar, or the national emblem of our northern neighbor. It is, in fact, the shape of the once ubiquitous car air freshener. Dolev takes the sensorial content a step further to convey a message about the damage we continue to inflict on Mother Earth.

Returning to the vertical leeway taken by a couple of contributors to “More than One,” one could point to the dimensional liberty taken by Malachi Sgan-Cohen whose Phantoms of Modernism (Geometry of Fear) series of digital drawings seems to spring from the wall. They appear to borrow from the world of animation and suggest a sequential flow as the human figure gets into all sorts of poses, some stranger than others. They also reference contemporary graphic novel art vocabulary and abstract modernist forms.

And there is Ronit Citri’s Proposal for Three Towers, which really does take flight from its flat base, with the three-parter comprising intricate pencil diagrams on transparent sheets placed over a text layer. In fact, therein lies a complex story that made it to a mainline media outlet back in the day.

The physical substratum for Citri’s triptych is provided by an article in Haaretz from 2010, which related the backdrop to the construction of the Wolfson apartment blocks that overlook Sacher Park and the Knesset. The initial idea was to put up three 29-story towers with plenty of room for public spaces betwixt. The municipal planning committee blocked the design partly on grounds of dented prestige – because the high rises would dwarf the Knesset.

Eventually, we ended up with five 16-floor blocks and precious little in the way of areas that serve the tax-paying public. The drawings echo the original concept, with Citri dividing the article into three sections, each with 29 lines

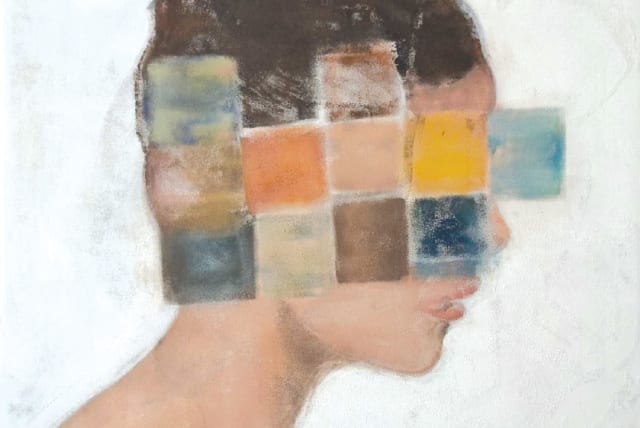

That suggests a political, socio-political and/or environmental subtext that surfaces in a number of offerings across the exhibition. Take, for example, Amir Tomashov’s series One Minute and Eight Seconds, which zones in on an event that presents consumerism gone mad. The title comes from the tsunami of shopping activity that took place on Singles’ Day in November 2019.

The unofficial Chinese holiday was originally meant as a swipe at the social stigma that goes with being unmarried but, over time, was turned into a national spending blowout. Tomashov’s moniker relates to the opening blast of the sales maelstrom three years ago when a reported $1 billion of transactions took place in the first 68 seconds.

We only get to see a handful of the full complement of the set, which takes in 21 drawings, but the varying degrees of pixelation convey a clear message of deconstruction, primarily of social values and possibly with some religious-spiritual meaning in there too. The drawings feature three commercial buildings from around the world that were demolished by natural disasters.

Tomashov neatly transposes the boundaries between media-reported reality and art, thereby getting us to observe and scrutinize the images from the consumer’s standpoint. And by removing parts of the scenes of destruction, the artist draws us into the subject matter by getting us to complete the picture.

CURATOR HADAR has done a good job with the placement and selection of the creations at Jerusalem Artists’ House and around town, and the series-cluster configuration makes for an alluring, intriguing and attractive viewing experience. She also had her work cut out for her, along with the curators of the other Biennale venues, eventually whittling down the responses to her call for submissions from a whopping 600 to 71 creations, 41 of which are on show on Shmuel Hanagid Street. There is, indeed, a sense of plentitude about the spread there.

The idea for “More than One,” of adopting a more accommodating approach to the standard physical confines of sheets of paper, Hadar explains, was basically just a matter of going with the conceptual flow. Clearly, there was a groundswell afoot.

“‘More than One’ actually came out of the fact that I saw I was getting a lot of series and clusters sent in, and I began wondering about the differences between them,” Hadar notes. “I thought series were linear and that they tell a story and are territorial and are even planned.”

Clusters were, she felt, a different kettle of fish. “You can look at them, from an artistic standpoint, in retrospective terms. You can add elements from beforehand and from later and from all sorts of stages, and even add something brand new.”

Hadar consigns the idea of clarity of delineation, and singularity, to the scrap heap of art philosophical thought. “When we look at series or clusters we are, in fact, talking about multiplicity,” she notes, adding that the approach spawned the Jerusalem Artists’ House layout baseline. “Multiplicity became the theme for the exhibition.”

That left the curatorial role free and breezy, giving Hadar plenty of leeway when it came to the screening process and how the selected works are presented to the public. She also feels there is an intrinsic element to the discipline in question that allows generous room for maneuver.

In complete contrast to my earlier supposition, Hadar says that drawing is a pretty ephemeral area of the arts. “Of all the various [arts] media, drawing is the oldest and there is no consensus of opinion regarding what constitutes drawing,” she states. “There are all sorts of attributes, which I would go so far as to call yearnings, that connected to it in all sorts of weird and wonderful ways.”

Rather than generating a sense of confusion and disarray, Hadar says the seemingly disparate parts make up a harmonious whole. “Somehow everything fits in with everything else. Some may say that drawing is limited to hand-drawn and expressive works. Others will say that you have to consider the paper and have a work plan. And there is digital drawing, which some would say is not compatible with manual drawing. Basically, everything goes together.”

DIGITAL CREATIONS also have their place in the exhibition, particularly Yoav Efrati’s On the Air series shown in a looped screened version. The easy come, easy go inference in the consumerism element to Tomashov’s One Minute and Eight Seconds set is alluded to in the Efrati video, too.

As the sequence is repeated over and over we are, of course, at liberty to follow the aesthetic development as many times as we wish. I found it to be a mesmerizing experience, following the way the images break apart and reassemble across a broad spectrum of positions and expressions, and all deceptively simple and, nonetheless, attractive.

Ecology also filters through in Ofra Eyal’s 2He slew of monochrome drawings in which she deftly creates the textural impression of helium, metallic-looking shiny Mylar balloons of the kind that used to grace the ceiling of the cavernous Arrivals hall at Ben-Gurion Airport.

The objects imbue a sense of romanticism and delightful weightlessness. But one can’t help pondering the oxymoronic circumstances of industrialized, definitively non-biodegradable objects floating up into the blue yonder without a care in the world.

There are gallery talks with some of the curators and participating artists lined up on various dates throughout the Biennale, which closes on February 25. ❖

For more information, visit www.art.org.il.