If the name Anatoly Kaplan doesn’t ring a bell, you are probably in good company. But now, thanks to Beit Avi Chai and the efforts of executive director David Rozenson and artistic director and chief curator Amichai Hasson, the name and legacy of the Soviet Jewish artist is reaching wider circles of the Israeli public.

The Enchanted Artist is one of the most expansive and adventurous art exhibitions that Beit Avi Chai has ever produced, with many of the exhibits coming from the Isaac and Lyudmila Kushnir Collection in St. Petersburg. It opened on January 19 with close to 100 works spread across the walls and in display cases on three floors of the Jerusalem cultural center.

As you move into the entrance level display area, you immediately get some sense of the creative, cultural and emotive depth of Kaplan’s oeuvre. Rozenson freed up a couple of hours to walk me through the exhibition and enlighten me about the fascinating backdrop to the artist and his work.

There is a lot to take in, and Rozenson helped me with some pointers from the outset. “There are three main parts to the exhibit. The one main part is to show Anatoly Kaplan as this Jewish Soviet artist.” That’s quite an opening statement. As we know, the Soviet Union did not take too kindly to the practice of religion by ethnic minorities – the ubiquitous Orthodox Russian Church was an entirely different matter – so, how did Kaplan swing that and avoid being banished to some gulag? “He was very much Jewish in art,” Rozenson adds.

How he managed that is not clear to begin with, and there are references to his religious-ethnic roots in numerous pieces in the show, across several disciplines. There is a small section on the entrance level devoted to ceramic works, including a sumptuously colored circular glazed fire clay plate titled Prayer at the Synagogue.

There is no mistaking the scene with men in tallitot [prayer shawls] shown from the front, and a figure in a rich red cloak, complete with a golden Star of David, facing something that may be the holy ark. It dates from the 1970s – Kaplan died in 1980 at the age of 77 – shortly after the artist got into the ceramic side of things.

True to his free-wheeling spirit, he took a singular approach to the raw material, trying his hand at fire clay, molding, painting, glazing and, on occasion, even applying slabs of clay to the source substratum. Judging by the display at Beit Avi Chai, the end product is a wealth of hues that make for engaging viewing.

Conveying Jewish roots through art

Soviet dictates or not, it seems that Kaplan (pronounced with the emphasis on the second syllable) was strongly connected to his Jewish roots and simply had to convey that in his art. “He was born in a shtetl called Rogachov (now in Belarus), where the Rogatshover gaon came from,” Rozenson explains.

Rabbi Joseph Rosen was born there in 1858 and was considered to be one of the foremost Talmudic scholars of his time. Celebrated Yiddish poet Shmuel Halkin, a contemporary of Kaplan’s, also hailed from Rogachov. Despite its diminutive population, it appears that the artist had plenty of spiritual reference points to feed off in his youth.

Still, Rozenson points out, this was a definitive backwater in terms of the opportunities available to the young man if he really wanted to make progress in the field. “He moved to Leningrad – at the time it was Petrograd – in 1922 because there were no academies of drawing [in the environs of Rogachov], and Petrograd had the best academy for drawing.”

The youngster may have been starry-eyed but you don’t just ride into the big city, declare your artistic intent and wait for the red carpet to be rolled out. He must have had some natural gift in the field. “He was good enough to get accepted as a student,” Rozenson confirms.

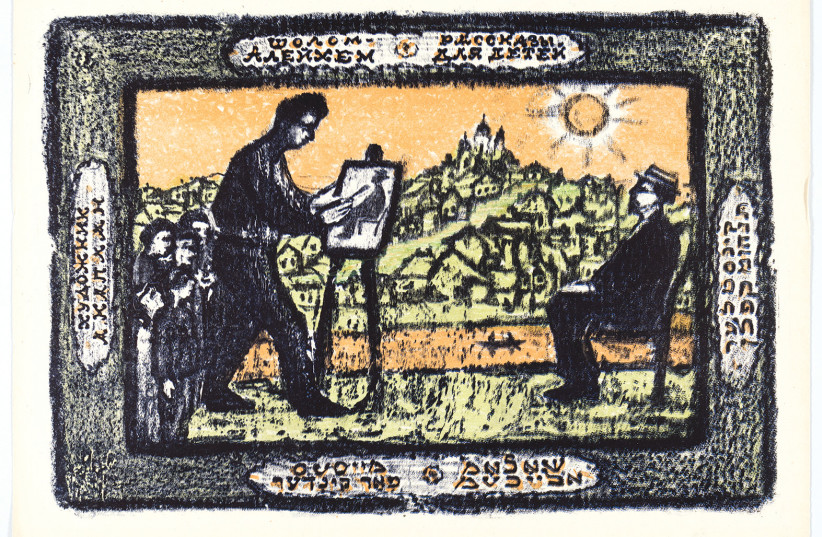

Kaplan clearly kept his options open and was ready and able to venture into all sorts of areas of creative pursuit and cultural sectors. The latter led to him lending his knack for coming up with arresting illustrative complements for books by preeminent Russian Yiddish author and playwright Shalom Aleichem, including The Enchanted Tailor and Tevye the Dairyman, better known as the basis for Fiddler on the Roof.

That is given its due at Beit Avi Chai. “The second part of the exhibition is to show his connection to classical Jewish literature,” says Rozenson. Quite a few literary giants of the 19th and 20th centuries benefited from Kaplan’s artistic input, with covers of tomes by the likes of Polish Yiddish writer and playwright IL Peretz and pioneering Lithuanian Yiddish and Hebrew writer Mendele Mocher Sforim featuring in the exhibition.

Connection to classical Jewish literature and work as a universal artist

Rozenson says it wasn’t just a matter of embellishing literary works with attractive jackets and pictures between the words inside. “He didn’t so much create illustrations for the stories, he created folders that were separate from the books.” They were considered artistic entities in their own right. “In East Germany, they published them separately.”

THE CO-CURATOR feels, however, that describing Kaplan in terms of Eastern European-Russian culture alone would be an injustice. “The third thing is that we need to show him as a universal artist,” he notes, bringing in some big guns. “He has been compared to [Jewish Russian French artist Marc] Chagall and [Belarus-born Jewish French painter Chaim] Soutine.” That is illustrious company indeed.

Kaplan’s public profile is nowhere near that of Soutine’s, not to mention Chagall’s, especially in this country where the latter enjoys particularly lofty status. Rozenson attributes that to the simple fact that Kaplan lived his entire life in Russia – the Soviet Union – hence, opportunities for seeing his work in the West were limited.

Then again, over the years he did have some showings in important museums and galleries, including MoMA in New York, as well as in Amsterdam and London. “He was never allowed out [of the Soviet Union],” Rozenson continues. Mind you, he did eventually achieve success in his homeland. “At one point, he was the biggest-selling Soviet artist, certainly in Leningrad.”

That may have been gratifying for Kaplan, but he wasn’t about to become a millionaire, certainly not as a citizen of an authoritarian regime. “He was selling very well; but according to the Soviet system, he was only paid two percent of the sales.”

No doubt, had he been able to get out to the free world and spread his wings, Kaplan would have made it big. Still, Rozenson feels there was something about the artist that lent itself to more a modest lifestyle. “The truth is, in many ways he always remained a boy from Rogachov. He was never a self-promoter.”

It seems that you may be able to take an artist out of the shtetl, but it is not a two-way street. “In his communal apartment, where he lived [in Leningrad] until he got a private apartment, he drew the images and memories of the shtetl. His mind was always there.”

That was uppermost in the curators’ minds when they got down to the task of presenting Kaplan’s work to a largely unsuspecting public. “This is a series called Rogachov,” he says as we get to a delightful drawing titled Grandfather and Grandchild.

It is something of a minimalist effort in which Kaplan manages to convey an abundance of emotion and the sociocultural and personal setting with just a few strokes of his pencil. The monochrome picture shows a boy and a bearded man wearing a kippah, who clearly have great affection for each other. But there is also some disturbing undercurrent in there.

The artist has created a pleasing composition by setting the two figures at an intriguing, but somehow agreeable, angle to each other, with a sprinkling of modest shtetl-like dwellings in the background. The tenderness between the two may be there, but their facial expressions suggest unease and possibly extreme concern.

This is not the product of an artist kowtowing to the regime in order to appease the authorities and thereby earn the right to continue with his craft. “He made this toward the end of his life, when he no longer had to hide his Jewishness,” says Rozenson. “This is about what he remembers of his own life.”

That, of course, suggests the comforting aura of nostalgia, of falling back on one’s earliest memories of far-flung youthful insouciance. But even Kaplan’s thoughts of his roots were sullied by the murder of his parents by the Germans in 1941.

By this stage, Kaplan had begun to let his hair down, although apparently he kept the flame of free, uncensored creation flickering throughout. “There is a saying in Hebrew, and in English too, I think, that he painted for the drawer,” Rozenson explains. “He painted and drew things that he never exhibited. In his apartment, there were hundreds of works that he left behind.” Thankfully, some of them have now made their way to Jerusalem.

IN TRUTH, however, Kaplan seems to have been adept at tiptoeing his way through the minefield of communist repression and somehow portraying Jewish themes regardless. That indeed became more apparent in his later years, and the delicate balance between keeping up compliant appearances and depicting his inner thoughts and feelings is palpable in Interior.

The softly hued tempera on canvas painting shows an apartment living room with a mother tying the obligatory Young Pioneers red neckerchief on her daughter while her father secretly prays, complete with tallit and tefillin [phylacteries], in a back room.

As Rozenson notes in the catalog: “In his work, Kaplan addresses universally pertinent issues: how to maintain Jewish tradition in a secular world. Where to find the inner strength to be loyal to Jewish tradition while attempting to acculturate into wider society. These questions are as relevant today as they were in the difficult world of Soviet Leningrad.”

The flip side of Kaplan’s longing for his Jewish roots patently comes across in Monument to the Red Army, another tempera painting. This is a very different affair, with two couples of different ages standing with bowed heads on either side of an obelisk topped by a communist star. That looks like a bona fide salute to the powers that be, but Rozenson feels there are some subtexts in there as well.

“The communist star has five points and could be an adaptation of a Star of David,” he suggests. “And look at this [older] man on the left. He may be the father because he has a beard, but he doesn’t really look older.”

Age fluidity also appears in an attractive work in which Kaplan depicts himself creating a portrait of Shalom Aleichem whom he never met, and who died when Kaplan was only 14.

Kaplan’s standing with the Soviet authorities was certainly helped by some of the works he produced in the 1940s as Leningrad began to recover from the ravages of World War II. Looking, for example, at the Rebuilding St. Isaac’s Square lithograph, you could easily conclude that the artist was a staunch believer in communism, who loved Mother Russia.

Natalya Kazyrova of the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg effusively described Kaplan’s Leningrad Series as “one of the most striking and poignant declarations of love known to world culture.” The artist didn’t do too badly out of the effort, either. When the series was published in 1946, it was acquired by 18 museums across the Soviet Union and made Kaplan a household name behind the Iron Curtain.

There is also plenty of symbolism in Kaplan’s oeuvre, including the frequent appearance of goats, often shown resisting the owner’s efforts to make headway. “A goat was also a sign of wealth in the shtetl,” Rozenson explains. “If you had a goat or a cow, you had milk and could feed your children.”

That also puts one in mind of Israeli sculptor and painter Menashe Kadishman, who died in 2015, for whom the goat was an instantly recognizable leitmotif. Kaplan also, naturally, incorporates goats in his color lithograph Chad Gadya series.

The Enchanted Artist is clearly a labor of love for Rozenson, who was born in Moscow and left with his family for the US at the age of eight. The bond with Kaplan quickly becomes apparent.

“For me, this is so meaningful,” he says, nodding in the direction of Grandfather and Grandchild. “My grandfather came from Rogachov. As I looked at this for the first time at a friend’s apartment in Moscow in 2000, I saw my own grandfather.”

Therein also lies yet more emotive biographical content. “Kaplan didn’t have any grandchildren of his own. It is as if he left a grandchild through his art, for us and for the future, to show a continuation – my art is what continues myself.”

Hopefully, now that the word about Kaplan is out there at Beit Avi Chai, the artist will get his due here and elsewhere around the world. ❖

‘The Enchanted Artist’ closes on August 31. For more information: www.bac.org.il/exhibitions