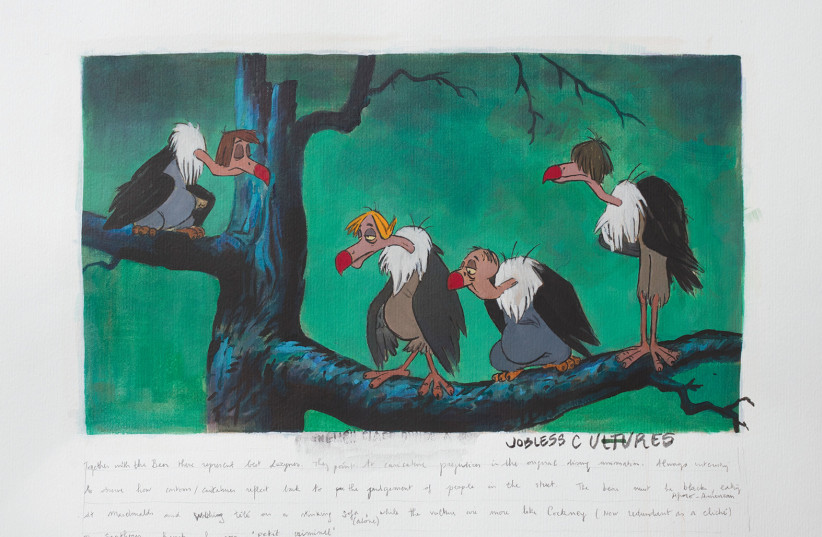

With hindsight, it is often easy to arrive at the seemingly obvious idea that some artist – a writer, for example – had some kind of philosophy in mind when he or she wrote a particular book when, in fact, that may not have been the case. Be that as it may, Rudyard Kipling’s timeless tale The Jungle Book continues to delight youngsters, and adults, to this day. Mind you, that is largely due to the 1967 Disney animated version rather than the actual physical tome written over seven decades earlier.

It is the film that first catches your eye as you enter the Facing the Wild – The Jungle Book Revisited exhibition, which opened at the Israel Museum in December and runs through to June 17.

According to curator Talya Amar, ecology and the delicate yin-yang balance between human beings and animals was very much part of Kipling’s agenda. “You could say the exhibition was inspired by The Jungle Book, but it takes things out of fiction and more into reality,” she notes.

It is the relationship between people and animals, and how we interact and respect each other, that provided the launching pad for the exhibition. As one of many strands to the subtext of the Kipling tome, the show examines the dynamics at the core of our increasingly unnatural and technologically advanced way of life, and the natural world around us.

As many of us will recall, the Disney film ends with Mowgli, the “man cub,” having to decide whether he belongs to human civilization or in the jungle with his old pals – the long-suffering dependable panther Bagheera and the fun-seeking, free-loving bear Baloo. The quandary reemerges in the sequel, The Second Jungle Book, which Kipling released a year later, a venerable copy of which is on show at the museum.

There is much to see, and ponder, in Facing the Wild.

Amar says it is not just about maintaining a delicate equilibrium between industrial progress and the needs of Mother Nature which, clearly, have to be accommodated if we are going to continue populating this speck in the vast universe. She suggests that our approach to animal life is also very much a matter of conditioning.

“We are talking about animals in the wild. But there are also pets, and sometimes we relate to animals more in terms of the images that have been created.”

Good point. Some may look upon, say, squirrels as delightful creatures that scurry among the trees and nibble nuts and other tidbits in an entertaining way. Or you could take the less complimentary view an old friend once expressed when he called them “rats with bushy tails.”

Our individual take on animals is very much behind the thinking of The Jungle Book Project video installation created by Pierre Bismuth. The 59-year-old Oscar-winning French filmmaker and artist has made a habit of revisiting familiar works, deconstructing established codes and reinterpreting them. In so doing, he offers us the opportunity to reexamine symbols that have taken on axiomatic status, thereby allowing us to discern and, possibly, weigh up previously hidden meanings.

There is nothing like shuffling the pack to shake us out of our comfort zone. Bismuth achieves this by simply having Bagheera, Baloo et al speak in foreign languages. The good-natured bear, for example, speaks in Hebrew, while the panther talks Arabic, and Mowgli speaks in Spanish. And it is, surely, natural for Shere Khan, the wily antagonist tiger, to take on the polished vernacular and accent of an English aristocrat.

That suggests a Tower of Babel scenario in which the characters speak languages that are incomprehensible to one another, which forces the viewer to do a double take on well-trodden ground. That also begs the question of whether being forced to take a step back from the conventional line necessarily involves a rethink and impacts our perception of reality.

THIS IS a powerful layout which conveys the ecological, existential message in no uncertain terms. There are exhibits that initially come across as entertaining items but, as you observe, it gradually dawns on you that there is more to the work than first meets the eye and, occasionally, ear.

There is a niche at the far end of the display area with a giant plasma screen. The high-resolution filmic content immediately draws you in, although you quickly move beyond the captivating aesthetics of Doug Aitken’s suggestively named migration (empire) and begin to consider what is actually going on in there.

What, for example, is an angelic-looking fawn doing with its cute head rummaging around in a hotel fridge? Why, in God’s name, are there all kinds of creatures, that normally steer a wide berth around our neck of the unnatural woods, prowling through a plush hotel room, striding across its soft carpet, tearing pillows – stuffed with bird feathers, one might note – to shreds? The cushion assailant, by the way, is an owl – the symbol of sagacity.

What is going on here? What on earth are these wild, uncivilized intruders doing, trashing the trappings of the privileged like some rampaging 1960s rock band?

By the same token, would we also question the incongruity, if not downright offensiveness, of coming across a packet of potato chips or discarded can of Coca-Cola along a nature trail?

Aitken’s message is clear and uncompromising. Set in a post-apocalyptic world, we see animals, at first hesitantly doing what comes naturally to them – sniffing around for danger – before getting down to foraging for food. The exploration of unfamiliar conditions takes on a more feral vibe when the creature begins to get down and dirty with the fixtures and fittings. After all, they are only following their instinct.

Does, one wonders, the same apply to us? Are we driven to distance ourselves from the natural world, making it less and less habitable in the process, by some survival mechanism? Is it always an “us vs them” scenario, or would we be better advised to adopt an accepting standpoint and abide by the natural laws of the jungle?

Aitken conveys a sense of just how far we have moved away from the God-given elemental Garden of Eden, creating for ourselves a sophisticated, artificial world in which there is little room for animals to do their instinctive thing.

He ups the doomsday philosophy ante by housing the 24-and-a-half-minute work on a billboard-shaped screen. That is designed to reference the strip mall mentality as commercial outlets, where we often spend money on products we don’t even need, proliferate on the outskirts of towns across the US, and tarmac and concrete cover ever-increasing tracts of land, pushing the global thermometer up even higher.

Facing the Wild comes with an observation caveat. “This exhibition contains works that some might find upsetting,” the organizers caution. Ursus Maritimus by American artist Mark Dion certainly stokes the emotional embers. The title is Latin for “polar bear.”

That’s exactly what you get stretched out on a large packing crate. The figure of the majestic-looking, gigantic white-haired predator makes for an impressive and convincing spectacle. It is also a bit challenging to consider that a taxidermist has taken the body of the imposing animal, gutted it, and stuffed it with some durable material solely for our viewing pleasure.

As the accompanying text becomes legible, you discover that, in fact, at least on this occasion, the exhibit was not hurt and that Dion created the prone artifact out of mostly man-made substances, albeit with some actual goat hide thrown into the artistic mix.

The reality check factor is accentuated by the presence of monochrome photographs of actual stuffed polar bears, previously exhibited at museums and research institutes over the years, on the walls surrounding the “bear.” Dion sounds a clarion call on global warming, wanton hunting, and the consumption of meat. He advises that “in the 19th century, the polar bear was presented as a fearful monster with sharp claws. Nowadays, as a vulnerable creature that needs to be protected.” Makes you think and, surely, balk.

Blood Red Tiger Head, by French-domiciled Chinese painter Pei-Ming, is a palpably emotional creation that stops you in your tracks. The large canvas – Yan generally thinks big – is an expression of primal majestic power. There is no doubting the robustness of the creature that appears to have its hypnotic stare fixed firmly on you.

There is no escaping the gaze or the hulk of its proud corporeal shape heading straight for you. It is only when you get close up to the oil painting that you begin to absorb the abstract textures and elements. The demarcation lines between reality and imagination blur, in a recurring theme across the layout.

Hunting – breadwinning in its modern-day guise – is traditionally perceived as a masculine activity, even though we know there were matriarchal societies back in the day, where women ruled the roost and, literally, brought the bacon home.

We get some female, and feminist, input from German-born American Kiki Smith. Her large ink and graphite drawing on paper, loaned out by Centre Pompidou in Paris, offers a softer approach to the human being-animal relationship and existential conundrum.

Lying with the Wolf depicts a wolf embraced by a woman that projects a sense of tenderness, intimacy and harmony. Smith proffers the idea that it is perfectly possible for us to live together in mutual acceptance and symbiotic symmetry, replacing the predator-prey mindset with trust and companionship.

This is not a new idea, although clearly one that could do with a reprise. Roman mythology, for example, has a she-wolf suckling twin brothers Romulus and Remus – the former is said to have been the founder of Rome. Lying with the Wolf also alludes to the fifth-century CE figure of St. Genevieve, patron saint of Paris, who frequently appears in Christian art with a wolf by her side.

“They are almost a single entity,” Amar observes. “There is intimacy and tranquility, which contrasts with the idea of two alpha males dueling.”

THE SET of inkjet prints by Israeli artist Pesi Girsch justifies the viewer guidance statement. Her six-part series features animals slain by hunters, a couple of tigers inadvertently killed by their own mother following lengthy incarceration in a zoo, an otter that froze to death in a similar public leisure facility, and even a deer displayed as a hunting trophy.

Girsch would like us to relate to animals as we would have them treat us. “The attention I pay to animals – who are like people – and to those lower down on the ladder is what I seek for myself: to protect and be protected.” For some reason, it brought to mind high-earning politicians.

The tension, and life-and-death cycle you sense in the works, partly feed off Girsch’s own backdrop as the daughter of Holocaust survivors.

Interestingly, she chooses to portray her subjects in pristine contexts, cleansed of their bloody origins. That serves to enhance the power of the images with an oxymoronic undercurrent.

“Girsch seeks to restore her subjects’ honor,” Amar says. “They all died, directly or indirectly, due to human intervention. Pesi lives with animals. For her, the suffering of animals is the suffering of the whole world.”

Facing the Wild – The Jungle Book Revisited is an expansive continuum of entertaining, eye-grabbing, emotive, endearing, shocking and moving works that leaves the observer with a palpable sense of empathy, and plenty to mull over. ❖

For more information: www.imj.org.il/en