This has never happened to me before: having to check if each of the nine artists I spoke to or anyone interviewed for this article were still alive, ahead of its publication.

Although this sounds surreal, it is so very real. Fortunately, they are all alive.

We are in a horrible war without precedent for which we were not prepared. With the loss that we are experiencing as Israelis, as Jews, as a nation and individually, I ask myself whether we need art in wartime and what the role of art is in this time of sorrow. I posed this question to one of my friends in Tel Aviv just after another siren had gone off. She replied: “Everyone needs it, especially in these times!”

Reflecting on this response, I recalled how comforting art was to many of us during the pandemic in 2020. In fact, over the past few years I have introduced readers of the Magazine to many artists whose output evolved during the COVID-19 period, as well as to those who discovered their hidden artistic talents as a way of dealing with shock, isolation, and loss.

Art can help people cope with trauma. It can transport both its viewers and its creators to a different reality, to a different world. And this can have a curative effect. Especially when it comes to watercolor – due to the specifics of this technique and material – art can also be a way of documenting reality.

During the pandemic, Yonat Cintra dedicated a series of her watercolor paintings to her desolate neighborhood in South Tel Aviv. I asked her today (October 15) whether she is painting, and she replied in a text message: “I started going to the studio last Thursday. I just feel I have to work on something related to war…”

She added: “In the stressful reality like now, I find my alertness tuned to the creative process.”

Shirley Siegal, whose son, daughter, and partner were drafted last week, decided to create an album of war paintings. She texted, “I walk around the streets, collecting photos of volunteers, guards, and soldiers… This is also a way to cope.”

“STILL WATERS into Living Colors,” the nine-artist exhibition with nine story lines and nine approaches to watercolors, can help us remember our humanity, which no terrorist can take away from us.

Whoever visits the Old City of Jerusalem and looks up above its walls will see from afar the characteristic arches of the Brigham Young University Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies (BYU). However, not many may know that they can visit an art gallery in this mysterious building on Mount Scopus and watch a stunning sunset overlooking the city from that spot. The view is captivating. In the gallery, the rays of the sun seem to play with the colors and lights of the paintings that hang on its walls.

Preparations for the exhibition began in 2019 but were interrupted by the pandemic. When curator Lola Vilenkin returned to the project, the collection was updated and completed, with paintings illustrating the reality of the lockdown. Some of these are far from the romantic images one might traditionally associate with watercolors.

The exhibition features some of Israel’s most renowned watercolorists: Yonat Cintra, Inna Davidovich, Meydad Eliyahu, Maureen Fain, Beni Gassenbauer, Rachel Kainy, Sara Sefton Shor, Shirley Siegal, and Pamela Silver.

They represent varying generations and backgrounds in art, demonstrating their distinct and personal approaches, techniques, and conceptual methods, infusing the medium with ingenuity and creativity.

Water, pigment, and paper

As many of the artists told me, what they love about watercolor is its freshness and irreversibility. Water, pigment, and paper are what these artists have in common. All the rest, such as the way they use color, the size of their paintings (from little sketches to paintings stretching a few meters – unusual for this media), and their topics of interest are immensely diverse.

Some artists work in real-time, using their brushes and pigment, while others prefer to first capture the images in sketches or a photograph and elaborate on them afterwards.

Maureen Fain, for instance, never takes photos of the people she paints. This experienced aquarellist and watercolor teacher creates deeply personal portraitures, revealing her profound sensitivity as she skillfully unveils her subjects.

Her portraits are detailed, but she tries to be tactful (for example, by illustrating her models’ personality rather than their wrinkles). Fain captures the presence of her models.

“I talk to them while painting; we have conversations because I like to go deep and show more than just features,” she says, underlining that she paints quickly (each painting takes her about an hour or am hour and a half) because she likes to maintain immediacy.

“Watercolors are a very interesting medium; you have to think about so many things: time, colors; and when it comes to portraits, likeness.” She considers herself lucky to have a classical background in art (from art academies in South Africa, England, and Israel) but considers herself an “instinctive” painter.

About watercolors, Fain says: “This is the most wonderful, challenging, and free medium. It is so immediate and fresh. Of course, everyone has their own way. But it is magic because you actually can’t know too much about what is going to come out. You take chances, which I love.”

She describes her process this way: “You sit down, and it is going to work wonderfully – and sometimes it doesn’t. The water does what it does, the color moves, and the paper changes everything. It is always very inventive and always very exciting.”

A completely different approach can be seen in the works of Shirley Sigal, who appears in one of own her paintings because she paints from photos of the scenes that she documents in her aquarelles. Sigal is fascinated by archaeology and joined official excavations where she has documented first encounters between people and history.

Although completely different and less precise than Sigal’s brush use, another type of documentary work is presented by Jerusalem-born Tel Aviv resident Yonat Cintra. In the series “The Love Song to the Neighborhood,” Cintra takes us to the kaleidoscopic realms of South Tel Aviv’s Shapira neighborhood in cityscapes painted during the pandemic, when the artist developed a new relationship with her neighborhood.

“I walked around my neighborhood during the first lockdowns [in 2020], when we could only go 100 meters away from home. So the small paintings on view at the exhibition are pages from my sketchbook,” she says.

“The city was very empty and quiet; not the urban scenes that I was used to from South Tel Aviv. Because of the coronavirus, there was fear. I think the watercolor was able to catch the essence of the moment,” she explains.

In her work, Cintra also uses different media, but she enjoys watercolors because of their spontaneity and lightness.

“When something happens on the paper, a mistake, something not planned, it stays as part of the painting. In this particular medium, I try to be less in control and [concentrate] more on transferring my feelings.”

A much more traditional approach to watercolors can be seen in the paintings of Beni Gassenbauer. He leads us to an entirely different world – on an enthralling journey through figurative sharp-focus landscapes and cityscapes, capturing with perfect perspective every detail, texture, hue, and interplay of the radiant Israeli sun. His works seem to invite us for a walk.

The way the exhibition is built, the walk continues to the streets of Nahlaot, beautifully captured by Sara Sefton Shor. She offers the viewers a glimpse into one of Jerusalem’s most charming and picturesque neighborhoods.

“For many years I had a studio in Nachlaot, and I would wander around this area,” says Shor.

In parts of the neighborhood’s architecture that someone else might have seen only as old, she sees their beauty. Shor breathes life into the worn city elements and transforms old dilapidated gates and walls. “This particular turquoise gate I painted a few times; it changes colors.” As for her method of working, she generally starts by painting on the spot, “but I take a photograph and continue at my studio.”

Similar to other artists that I spoke to at the exhibition, Shor likes that the watercolors let the artist be very spontaneous. “Once you put it there, it either works or it doesn’t.”

THE UNPREDICTABLE effect of this medium seems to be the attracting factor.

Keeping that in mind, the youngest of the artists presented as part of “Still Waters into Living Colors,” Meydad Eliyahu, has yet another approach. He also knows that what’s put on paper cannot be changed. Eliyahu is educated in Chinese and Japanese calligraphy and presents a series of works called “Weeds,” which one could easily mistake for Asian art. At least at first glance. Eliyahu continues the age-old tradition of botanical watercolor painting.

Eliyahu explains the unexpected events that triggered his project.

“It all started on the streets of Krakow, Poland, where I was working on another project. Since 2018 I have done a few artistic projects at the Jewish Festival in Krakow.

“I was staying there for a few weeks each time, and while being at Kazimierz [the Jewish quarter in Krakow], I had a habit of wandering around the city, and I had this intuition to draw. But in this once very vivid Jewish city, now I felt the absence of Jews. And I started to collect these weeds (kinds of grass) in the corner of pavements, then drew them.”

The paintings are black and white, with some metallic shine, and a special pigment.

“I had to limit myself to this palette [of colors]. I felt it was the right thing to do because of the subject of this particular series. It is not typical watercolor work,” he says. He compares this medium, in general, to life: “Like in life you do something and you cannot take it back, the same is true with ink and watercolors.”

And the unexpected, again, is what connects his work with that of other artists in the exhibition. But each interpretation of the medium is different.

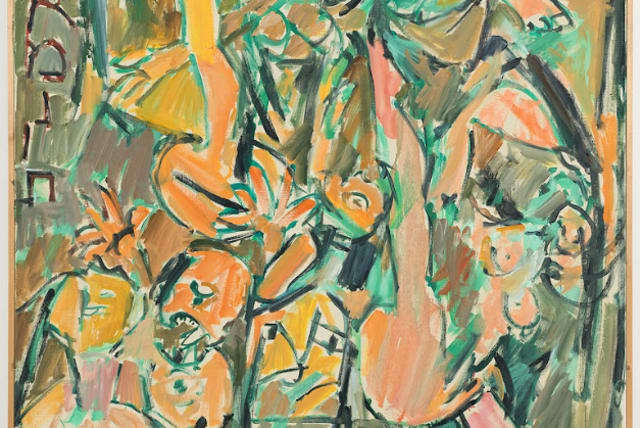

Rachel Kainy focuses on the conflict between nature and culture; she constructs a unique symbolic language. Her enigmatic landscapes and compositions in watercolor and ink embody personal, ecological, and historical themes, woven into a rich tapestry of cultural myths, global concerns, and personal associations.

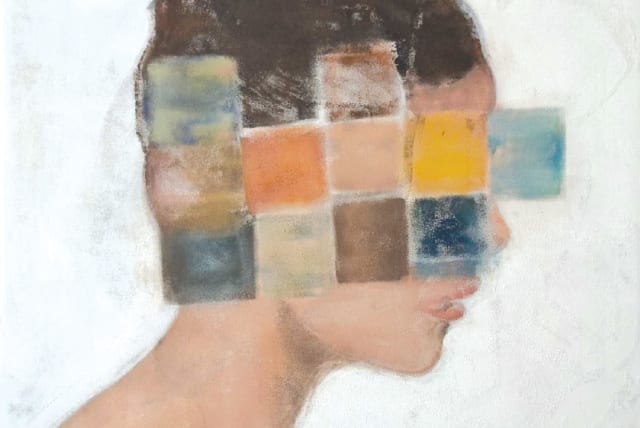

Looking at the works of Inna Davidovich, I thought of paintings on silk. Her works showcase another shade of the fragility provided by aquarelles. She maintains a delicate balance of color and form while employing various techniques and occasionally incorporating external objects like plates and mesh to create desired shapes and textures.

“Her abstract watercolor compositions are a testament to her versatile approach, inspired by the literary works of Italo Calvino,” explains the curator of the exhibition.

Independence is a tryptic by Pamela Silver. Atypically for watercolors, her paintings are enormous.

“Each of my paintings is 2.30 meters by 1.50 m. I painted them over 20 years ago. I used a huge brush, which I bought in China, and I just splashed the paint and golden powder on the paper,” she says. “One weekend when my husband was away, I had a huge feeling inside of freedom and amazing strength, and I put the paper all over the house [on the floor], and I moved with the energy from one painting to another; it was totally intuitive.”

As we talk, surprisingly, Silver compares the process of painting with watercolors to swimming: “Watercolors happen in one moment in time, it is a very strong feeling, like in swimming.”

Apart from swimming, Silver is inspired by nature. She uses both pastels and very energetic, intensive colors.

“They come very much from my fantasy world from childhood and pictures from my childhood [born in South Africa and from age four raised in Bulawayo, in present-day Zimbabwe]. I was surrounded by beautiful flowers and trees.”

The artist says that she doesn’t think of colors but rather she hears the colors and follows the voice inside of her: “Put this color now.” She moved to Israel 50 years ago and has always lived surrounded by nature.

Israeli watercolors have rarely been exhibited in such a major scale collection in one place and at the same time.

“Still Waters into Living Colors” offers a unique opportunity to enjoy their beauty – along with the outstanding view of Jerusalem from the balconies of the BYU Jerusalem Center. ❖

The exhibition at Brigham Young University will be on view until December 18. Due to the war, the gallery is temporarily closed. byu-jc.org/exhibitions