On a visit to Haifa embroidery artist Susan Shafrir in her Ahuza home, this writer was shown her preparations for her upcoming solo exhibition, “Fabrication,” opening at Haifa Auditorium on October 20.

Shafrir’s passion for Africa was sparked when she accompanied her husband, a doctor of dermatology, on a mission to Zaire (now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The trip was sponsored by the Foreign Ministry’s program Mashav, which provides aid to developing countries. The couple made several long-term visits. Shafrir loved the continent, so her social conscience deplored the abuse of Africa through the ages.

During the period of their work, there was a massive deforestation program. Foreign companies were destroying forests the size of Switzerland in order to obtain wood supplies. The denuded wasteland was then mined for lithium used for car batteries, and young children were sent into the polluted area to collect the material. The local pygmy population was then displaced in order to plant quick-growing maize.

During the time that Shafrir’s husband was working in the Congo to teach hospital management, Shafrir taught art and ceramics. But she could never forget the environmental and human abuse of the land and the people.

The abuses of colonialism

Going farther back in history, to the kidnapping of African communities for slavery in the US, there have been many works of literature and art exposing this abuse.

Renowned writer Rudyard Kipling was pro-colonization, assuming superiority of British civilization and their moral responsibility to bring their enlightened ways to the “uncivilized” people of Africa. Paul Scott`s 1966 novel The Jewel in the Crown exposed the brutality of the British rule in India, and Alex Haley`s 1976 saga Roots told the true story of the tragedy of colonization.

The developing countries are always used for experimenting on humanity. John Le Carré’s 2001 novel The Constant Gardener exposed the scandal of experimenting with hazardous medications. Lesser known is the sales technique of a well-known baby formula company that donated huge amounts of its product to impoverished mothers in Africa as a marketing technique, claiming that it was easier and healthier than breastfeeding. When the donations dried up, so had the mothers` milk; the families could not afford to buy more supplies, so they over-diluted the bottle feeds, causing malnutrition. The less than hygienic conditions for preparing bottle feeds with polluted water caused an epidemic of dysentery. The World Health Organization published a code of marketing of artificial infant foods, but there is still much unethical promotion of these products, in the Western world as well.

Therefore Shafrir’s social conscience inspired the talented artist to show through her artwork that this abuse never ends.

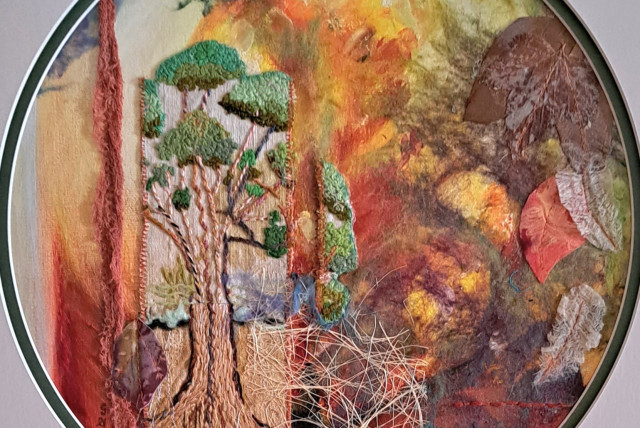

Her art form is fabric art, which is a mixed media technique of embroidery that uses threads and needles, paints, natural materials, fabrics and plastic waste.

One of her impressive pieces is an embroidered collage of symbols of the environmental and human disaster of deforestation titled When It`s Gone, It’s Gone. Looking carefully at this work, measuring 150x30 cm., one can interpret the symbols of wasteland, abuse of children, and population displacement.

“The flowers are machine embroidered to my design, loosely based on those that we saw there,” she explains. “I use gold and silver, leather pieces, and copper. The figures illustrating the worn-out children are my own drawings printed onto cotton. The background of the entire work shows the vibrant colors of Africa. It is fully lined with a hanging strip behind,” she explains.

Shafrir was born in England into a creative family. Her mother and both of her grandmothers were gifted embroidery artists. Although it was wartime, her family made sure she had art supplies, and she was already working with threads and needles at age six.

At art school, she studied multiple art forms and took an extra course in figure-drawing, graduating as a certified art teacher.

She is a member of the European Textile Network, as well as the London-based Society for Embroidered Work, for which she participated in a group exhibition in Rome.

Her first solo exhibition was at the age of 20. Since returning from Africa, she has had nine solo exhibitions and has participated in many group exhibitions.

After her marriage and aliyah, she worked as an English teacher at the University of Haifa and the Open University; but as their children grew up, she began to seriously apply herself to various art forms, working in water colors and oils. On a trip to England, she studied at the Embroidery Guild, using machine embroidery to create semi-abstract appliqué and collage.

“Although there were so many excellent and professional embroiderers in the UK, embriodery was regarded as women’s craft,” she says. “The Embroidery Guild lobbied the Royal Academy of Art, and the art form was upgraded to ‘mixed media.’”

The current exhibition is not the first time that Shafrir has created a polemic project through her art. In 2018, she was commissioned by the UNESCO Medical Ethics Committee to give a lecture and exhibit work describing cases where rules of ethics were broken.

The project, “Impact – Bioethics Exposed,” was exhibited at the 13th World Conference on Medical Ethics. It took over the entire Hilton Hotel in Jerusalem, and then moved to England. Shafrir had created artwork illustrating dilemmas in decision-making in the medical and legal field with the intention of teaching doctors and lawyers to consider the human consequences of their decisions. One example was the custody of frozen embryos, in a case where a couple divorced, the woman wanted to use the embryos, and the man refused. And we have all heard of cases where doctors have gone to court to overrule parents` life and death decisions about the care of a child.

“Art is a good additional tool to teach in medical school,” Shafrir says.

She had planned to take her work on medical ethics to Australia when the COVID pandemic broke out, and all travel plans were canceled. She had also arranged to send some of the artwork to Ukraine, when war broke out and again her plans were canceled.

Her upcoming exhibition, “Fabrication,” at the age of 85, will hopefully make up for those disappointments. It will certainly arouse the awareness of the power of large industries over vulnerable populations, causing environmental and human destruction. ■

‘Fabrication’ opens at the Haifa Auditorium on October 20, and closes on November 11. Susan Shafrir can be contacted at Shafrirsusan@gmail.com