The old joke in the art world is that if artists really want to make good money from their work, it can help to shuffle off their mortal coil. Just ask the specter of Van Gogh, who hardly made a sou out of his now universally lauded paintings that, should one ever come on the market, would sell for millions.

Thankfully, Amos Gitai is still very much alive and being consummately creative; but the 73-year-old internationally acclaimed Israeli filmmaker unwittingly stands to reap the rewards of a different horrific “marketing” development. If you are going to display an exhibition of works fueled by wartime angst and post-trauma, another local round of violence can do wonders to boost public interest.

Humor of the darkest nature aside, Gitai’s “Kippur: War Requiem” exhibition, which opened at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art a month ago, curated by Mira Lapidot with assistance from Amit Shema, and is due to run through to January, has accrued even more street-level credence over the past few weeks. Not that military clashes are ever too far from the regional agenda.

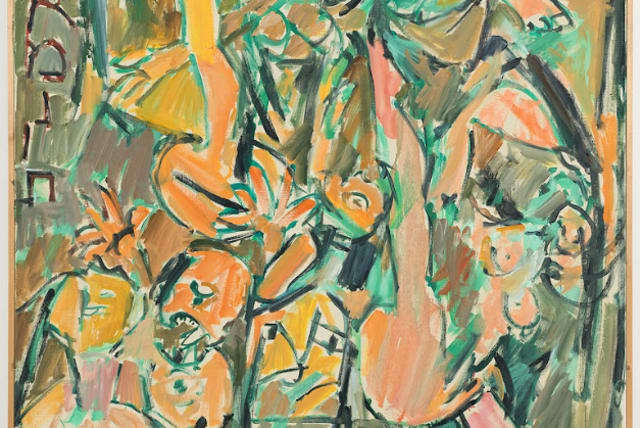

“War Requiem” is an arresting and, sadly, highly pertinent roll-out of the detritus of destruction, grief, and emotional scarring. Besides his best-known avenue of artistic expression on film, the spread takes in Haifa-born (and now largely France-based) Gitai’s efforts in the plastic arts field, including seemingly nebulous pastel paintings – both on blank pieces of paper and, tellingly, on newspapers of the day from 1973. There are video clips of interviews with some of the leading figures of the very real-life drama that erupted and gradually evolved across the latter part of that year and into the next.

Surprisingly, and intriguingly, the exhibition also features ceramic creations that echo both the paintings and some of the textural aesthetics of the on-screen footage you encounter in the second, fittingly cloistered, exhibition space.

There are numerous strata to “War Requiem.” There is, of course, the highly personal, painful level of an artist endeavoring to impart some of his angst, half a century after his young soul was rudely awoken from a then nicely meandering life path. There he was, studying architecture, dutifully – and/or willingly – following in the footsteps of his father, Munio Weinraub, a lauded architectural pioneer and leading light of the Bauhaus movement in Israel.

Everything was changed by the Yom Kippur War

But the Yom Kippur War changed that irrevocably. That, and a neatly mistimed gift from his mother. Gitai was born on October 11 but, crucially, Efratia gave her soon-to-be 23-year-old son a Super 8 movie camera a week or so ahead of time. Had she waited until the actual day, Gitai would not been able to document, in an impressively thoughtful and artistic manner, some of his experiences on the ground and in the air over the Golan Heights.

The present state of affairs here, and particularly the relevance of the heartbreaking events of the past weeks to the gruesome events of Gitai’s younger years, is not lost on the celebrated filmmaker and multidisciplinary artist.

“These days, we are marking 50 years since the Yom Kippur War of October 1973. That war shook the Middle East and confronted many people in this region with the fragility of their existences,” he notes. Sounds eerily familiar and chillingly contemporary.

Artists frequently respond to the zeitgeist but also to the way current events and mores impact them personally. Gitai is no exception.

“As for myself, I was in a rescue team by helicopter trying to save people and bring them back to hospitals,” he says. “I saw the terrible price of war.”

That is laid out for us, in no uncertain terms, in clips from Gitai’s 1997 documentary film Kippur War Memories. Again, Lady Luck was with him when, on his birthday, he came perilously close to the aforementioned Van Gogh corporeal maneuver. He and the rest of the rescue crew were flying over enemy territory when a Syrian rocket hit their helicopter. The co-pilot, Gadi Klein, was instantaneously killed, but the pilot, Avner Hacohen, managed to keep the helicopter airborne for a few more minutes before crash-landing behind Israeli lines.

Had Gitai not taken his mother’s present with him, it is highly likely that we would not have been able to view the dramatic and visually compelling clips we see in the exhibition, and he might have been designing – no doubt worthy – buildings for the past 50 years rather than making such acclaimed feature films, documentaries, and TV offerings as Kippur, which came out in 2000, with the director having a full 27 years to ruminate, process, and eventually express his military trials in aesthetic visual form; Kadosh from the previous year; Rabin, The Last Day released in 2015, two decades after the actual events occurred; and A Tramway in Jerusalem (2018). HALF A century on, after possibly the most formative event of his life, Gitai is still wrestling with his memories and trauma, and trying to make sense of it all. In an interview he gave in 2014, he muses that perhaps he survived the incident so that he could “tell people what is the meaning of war.”

He has the personal unenviable hands-on experience to tackle that. He was there, in the thick of it, in mortal danger, and witnessed unspeakable horrors and the results of humankind’s inhumanity to other human beings. He has the proven talent and filmic acumen to use an artistic vehicle to address the topic, but it is still much easier said than done.

Gitai dredges up a vignette from the 1973 war that for him was even more profound and illuminated the transition between terrestrial presence and moving on to the next world in a stark shockingly simplistic light. Famed Czech novelist Milan Kundera might have described that as “the unbearable lightness of being,” as per the title of his best-known tome.

“For me, the most shocking event of that war occurred before we were shot down,” Gitai recalls.

“I had just put an oxygen tube in the mouth of a seriously wounded colonel, and we were flying to the hospital. At some point, some notes he had jotted down before the war fell out of his pocket. I bent down to pick them up. They were about buying tomatoes at the market. When I stood up, he was gone – he had died. The passage from life to death had not been dramatic at all, and that in itself is the real drama.”

THAT MEMORY was stored away for another day, for an ensuing juncture when time and the sequential march of quotidian existence eventually enabled Gitai the filmmaker to get down to cinematic brass tacks.

“All of these elements constitute biographical material that is personal,” he suggests.

“But how does one make a film or an installation out of it? It is really an open question that I try to answer through the exhibition itself, by using the Super 8 films that I made during the war and the drawings that I did immediately after the crash 50 years ago. Also parts of my documentary film Kippur War Memories which I made 20 years after the war, and the feature film Kippur, 27 years after.

“Sometimes I ask myself, ‘Why did it take me such a long lapse of time?’ I think that right after the war, I wanted to forget. I did not want to talk about it.”

Initial architectural intent notwithstanding, Gitai clearly had the aesthetic nous to portray what he saw from the IAF helicopter in an inventive, absorbing, and provoking documentary format. Most of us, had we been handed a movie camera before being surprised with an opportunity to enter a feral military setting would, presumably, have perused the user manual and set about ensuring that the footage we caught was, first and foremost, in focus, and that it caught what we were seeing in as an intelligible way as possible. But, as the powerful filmic installation in the inner exhibition hall eminently demonstrates, Gitai instinctively grasped other less obvious dimensions of the unfolding drama.

We see, for example, blurred landscapes, trees, roads, and countryside as the helicopter passes overhead at high speed. That adds appreciably to the drama and conveys a palpable sense of the combat arena dynamics.

“During the war, I took this camera with me and recorded what I saw from the helicopter: faces, the texture of the earth, bits of rescue missions, and so on,” he states. “Paradoxically, it was all quite abstract.”

Gitai comes across as a deep thinker with a gentle demeanor, although he doesn’t tend to go for wisecracking. He did, however, undertake a subtle foray into the realms of risible fare when pondering the role of his principal tool of artistic expression, and whether his mom’s birthday gift may have helped him get through the Yom Kippur War in a half-decent emotional state.

“What did I learn again now? What does the transposition of this event into an exhibition show me again?” he muses. “I can see again that the camera served as a sort of shield. The camera was a chronicler of that time. In this sense, it’s the modern fetish par excellence.”

In an interview he gave to TV personality Kobi Meidan in 2013, when he returned to his first career path choice with the making of a series about Israeli architecture, Gitai cited his mother’s darkly humorous response when she was called by an IAF clerk who informed her of the helicopter crash. “She said, ‘It’s good he was wounded, so he won’t return to the war,’” the filmmaker chuckled at the time.

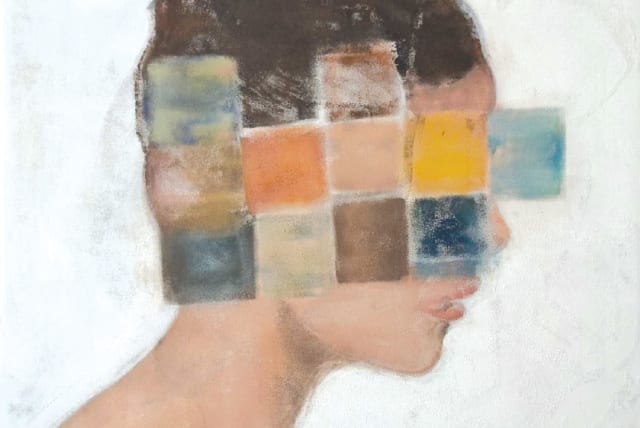

But comedy is not a major player in “Kippur: War Requiem.” The cinematic installation makes for eye-grabbing and breathtaking viewing and listening, with four giant screens showing scenes from Kippur in top-of-the-range high density. The potent large format presentation is augmented by slivers of other Gitai works projected onto roughly fashioned slabs reminiscent of outsized gravestones. The projection surface is a roughly hewn affair, with a seemingly random tactile concoction of sheeting – possibly alluding to hospital beds or the polychromic love scene from Kippur – plaster and all sorts of basic odds and ends. It is a beguiling sensorially sculpted oxymoronic combo.

GITAI IS keenly aware of the new context in which “War Requiem” will now be viewed. And while he mourns the savagery of Hamas, and the suffering of the victims, he clings on to some hope of a better future and the idea that his field of work may, in some small way, help to move things in the desired direction.

“My films are driven by the idea that we can build bridges, not burn them,” he says. “The recent performance I did at the Théâtre de la Colline [in Paris] included Israeli, Palestinian, and Iranian actors. I think that art must cross borders.

“On the other hand, I do not think that art changes reality. The example that I frequently give is that of Picasso’s Guernica. Picasso was very shocked by the Luftwaffe bombing of that Basque town. His medium was painting, so he made a painting. Picasso did not win the [Spanish Civil] war, Franco did. But Picasso engraved it in the collective memory.”

That may be so, but Gitai believes the human spirit can eventually lead a path through the morass of political intrigue and military clashes.

“Reality does not change just because of money or machine guns; it also changes because of ideas and memories. The role of the artist is to preserve the ideas and continue the dialogue, despite everything.”

Hopefully, the hostages will all return home soon, as safe and sound as possible, and there will be plenty of time for reflection and introspection. Perhaps at that stage, a visit to Gitai’s exhibition may provide some nourishing and healing food for thought.

‘Kippur: War Requiem’ closes January 13, 2024. For more information: tamuseum.org.il/en/