Metropolises and centers of empires of old have always drawn people from far and wide to their fabled golden-paved streets. Over time, London, New York, Paris, Berlin and Vienna, to mention but a few urban sprawls, have taken on multicultural demographics, people in search of better job opportunities and, hopefully, better housing. That, it appears, also applied to Odesa of the late 19th and early 20th century.

The multifarious population of the port city that sits at the northwest corner of the Black Sea in contemporary Ukraine included Jewish people of letters and painters, some of whom eventually made the move to pre-state Palestine. In fact, the city founded by Catherine the Great in 1794 struck out boldly into new cultural, social, and other vistas and quickly became famed for its frontier spirit and willingness to push the envelope across a range of creative fields and walks of life. The work of some of the Jewish members of that pioneering crowd is currently on display in the Odesa – Tel Aviv exhibition at ANU – Museum of the Jewish People on the campus of Tel Aviv University.

The exhibition’s full title, Odesa – Tel Aviv: Hebrew Literature and Universal Art, reflects the aforementioned multidisciplinary content and is emotively subtitled A Tribute to the Ukrainian People.

A tribute to the Ukrainian people

The spread makes for fascinating and eclectic viewing. The artworks hung on the walls of the cozy display space offer a surprisingly varied aesthetic experience, taking in cubist-leaning works, surrealism, fauvism, abstract art, and graphic caricatures, as well as dipping deep into legend to portray mythological scenes. There are also a number of compelling portraits of impressionist painter Leonid Pasternak, poet Shaul Tchernichovsky, and writer Eliezer Steinman.

The latter also happens to be the Israel Prize-winning grandfather of Orit Shaham-Gover, chief curator of the ANU museum, who, she says, was in good varied company when things in Odesa took a turn for the political worse when Russia invaded Ukraine. “This special exhibition tells a unique local story, which in many respects also represents many other stories,” she explains.

“During the turbulent years of the second decade of the 20th century, two groups of artists created and worked in Odesa, which was a bohemian cosmopolitan city along the shores of the Black Sea: the ‘independent’ artists – painters and sculptors who had their eye on the West – dreamt of making universal art and espoused human freedom and equality, while hoping that their works would turn Odesa into the Paris of the East. The other group – comprised of the first generation of Hebrew-language authors who were part of the movement for Jewish national revival – dreamt of writing modern Hebrew literature. Both groups, who were closely connected and knew and supported each other, were forced to pack up their dreams and escape from Odesa following the Russian Revolution. Many of them came to Tel Aviv and created vibrant Hebrew culture here in the spirit of Odesa,” she recounts.

GRANDPA ELIEZER was at the forefront of that cultural milieu-leaping bunch, along with Shaul Tchernichovsky, Haim Nahman Bialik, Ahad Ha’am, and many other artists and writers who were at the leading edge of contemporary creation. It was, says Shaham-Gover, an exodus of gigantic qualitative proportions that left its mark on the cultural evolution not only of pre-state Palestine and subsequently Israel but also on the United States.

“A young American specialist in Odesa claims that every second American Jew claims to be originally from Odesa,” she laughs. That may sound like the stuff of urban mythology, but the curator says there’s logic to the argument. “First, Odesa was very cosmopolitan; and, secondly, it was also a port. Sometimes people went to Odesa for a few months or years before they continued on to somewhere else.”

Shaham-Gover adds that one-upmanship may also be a factor in the American Jewish cultural backdrop clamor. “People liked to say they hailed from Odesa because it was a special place. During the first two decades of the 20th century, there was a very special phenomenon which was also universal.”

The Jews had a lot to say about that. “It is important to remember that over 30% of the population of Odesa at that time was Jewish,” the curator notes. That took in a wide spread of people, nationalities, professions, and outlooks on life. “There were artists, haredim, and secular Jews, all sorts. And Odesa was the southern capital of Russian culture.”

Some of the “all sorts” Shaham-Gover mentioned weren’t of a particularly salubrious ilk. “Jews were involved in organized crime there; sex trafficking also began in Odesa.”

The curator gets back to the more positive stuff. “There were two kinds of artists in Odesa which, in fact, represent the Jewish response to modernism. One group was visual artists who chose the area of modernism that engages in universality, the spirit of humankind, equal rights, and connections between people. That’s a track that began with the French Revolution.”

That, she says, involved a complete break from local tradition. “These artists settled in Odesa and rebelled against the Russian painting style of the 19th century with religious elements.” Those were heady times. “They wanted to be Paris. They called themselves Paris on the Black Sea, and they painted in a similar way to surrealism, expressionism, Dadaism, cubism. They suddenly bonded with what was going on in Paris, in Western Europe of the day. They called themselves the Independents.” This – the Society of Independent Artists – was not an exclusively Jewish group. They, Jews and gentiles alike, distanced themselves from mainstream Russian artistic thinking.

LIKE MANY artists, they needed a patron. They found one in Yakov Peremen, a wealthy man who acted as an influential linchpin for the local arts community. He was a Zionist activist, collector of modern art, and bibliophile.

“He had a bookstore called Kultura. He put on exhibitions and was involved in all sorts of cultural activities. He was also a member of another group in Odesa which followed a nationalist philosophy. Modernism spawned universality but so did nationalism,” says Shaham-Gover.

The latter bunch had different, non-Russian ideas. “They were people who dreamt of becoming Hebrew writers. They wanted to write modern literature in Hebrew. These people are now commemorated in street names in Tel Aviv and other places,” Shaham-Gover says, such as “Bialik and [historian literature professor Joseph] Klausner.”

This was an entirely new breed of people of letters who were looking to break new ground and consolidate the image of the emerging new Jew, the Hebrew-speaking Jew. We get back to family business.

“One of these writers was my grandfather, Eliezer Steinman,” she states with a fully justified sense of pride. There are more notable genes in the family tree. The curator’s father, writer Natan Shaham, also won the Israel Prize for literature. “I don’t think I’ll get it,” she adds with a wry smile. Time will tell whether Shaham-Gover, an acclaimed writer herself, follows suit.

She says the majority of the Odesa scribes unit connected strongly to Zionism. “Not all of them were Zionists,” she says. “Achad Ha’am wasn’t a Zionist. Mendele Mocher Sefarim wasn’t particularly Zionist, but the group was connected to Jewish nationalism. By the way, that accounted for a very small minority of the Jewish people at the time, even though they mostly survived the Holocaust because of their philosophy.”

The difference between the disciplines proved to be of existential value to the literary gang. Shaham-Gover explains that the Independent artists did not make aliyah, while the writers relocated to the Holy Land. “The painters came to Israel only as rolled-up canvases in Peremen’s baggage when he came to Palestine. He put on exhibitions at his home and dreamt of bringing modernism here.”

Still, as many an oleh (immigrant) can no doubt testify from their own experience, the writers that came here were not entirely enamored with life in the Middle East. They missed the bohemian lifestyle, cafés, and laissez-faire spirit of the southern Russian port.

“People like [the city’s first mayor] Meir Dizengoff and Tchernichovsky and [poet and later political leader Ze’ev] Jabotinsky came to Tel Aviv, but they dreamt of Odesa. In some way, they were stuck in a kind of twilight zone, between here and there. They wanted to transpose Odesa culture to Tel Aviv, but that’s what all immigrants want,” she observes.

THAT BIFURCATED mindset eventually left its imprint on the first Hebrew city’s aesthetics. “Dizengoff envisaged a white city because Odesa was a white city,” Shaham-Gover notes. The mayor eventually got his wish when the Bauhaus architects, who made aliyah from Germany, built what is today the world’s most extensive exemplar of the fetching architectural style – also widely known as the International style – conceived by German architect Walter Gropius.

According to the curator, the unsettled approach to life here begat special artistic offspring. “The dream [of still being in Odesa] produced something else. The dream persisted.”

This thought informs the layout at ANU. “In that sense, the exhibition is very universal. It represents the human condition of the Jewish people in the 20th century. We all came from some kind of ‘there’ to some kind of ‘here.’ We dream of preserving ‘there’ ‘here’ and, in so doing, we create something new.”

That in a nutshell, says Shaham-Gover, is the core of the show. “That is what the exhibition means by ‘Hebrew Literature and Universal Art.’ One lot wants universal art, the others want modern Hebrew creation. The exhibition brings the two together.”

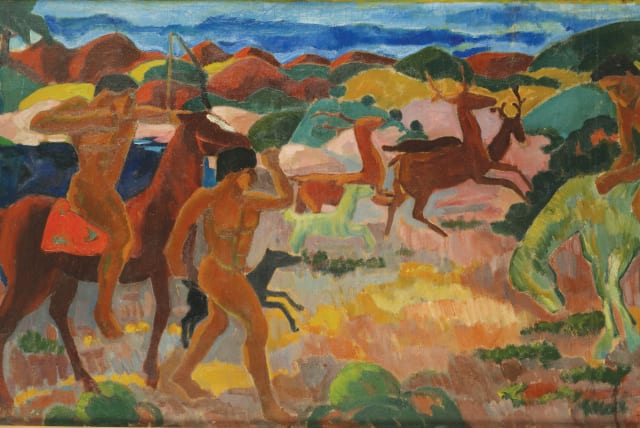

Wide-ranging avenues of thought apart, the works chosen for the spread by curators Lecia Voiskoun and Asaf Galay draw the eye and mind into the thick of the aesthetics and the creative and cultural dynamism that went into their birth. Isaac Malik’s painting The Hunt, for one, feeds off Russia’s far-flung Scythian era culture of the 5th century BCE, drawing on historical seams in a similar fashion as, for example, French artists.

Amshey Nurenberg’s Salome’s Dinner, from 1911, is also a brightly polychromic affair and seems to resonate the aesthetics of Paul Cézanne’s The Bathers. Nurenberg had clearly moved on to very different artistic climes by the time he got around to crafting Still Life with Skull, produced eight years later, which tends towards the more surrealistic side of art. Things move further into the realms of cerebral fantasy with two works by Sandro Fasini called The Architects and, fittingly, Surrealiste, both made in the 1930s in Paris.

There is also a display cabinet housing a 1923 edition of Steinman’s Esther Chayut; the cover of Bialik’s Every Day, illustrated by Haim Gliksberg and published in 1953; and Benjamin Schereschewsky’s The Six Orders of Science, published in Odesa in 1911.

The exhibition Odesa – Tel Aviv: Hebrew Literature and Universal Art covers extensive artistic, cultural, political, sociopolitical, and historical ground. It sheds much light on a fascinating passage of time whose ripples are still washing over us. ■

For more information: www.anumuseum.org.il