The art of Dalia Hay Acco appears to have been spilled, flung, splashed, and splattered on the wall. “I pour everything out; I’m drained, incapable,” says Hay Acco. “I drain, pour out.”

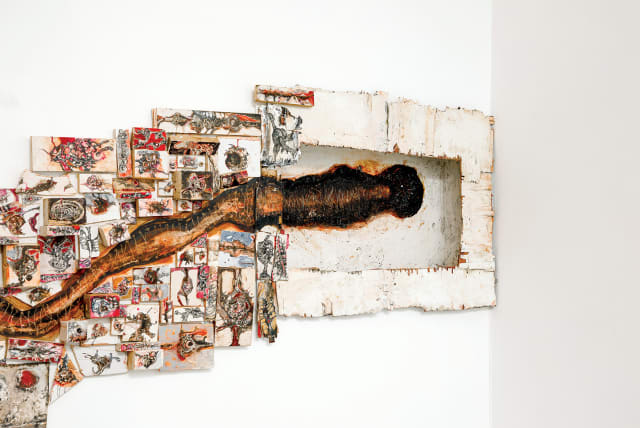

Her new exhibition at the Maya Gallery in Tel Aviv, curated by Ori Drumer, presents two bodies of work – large-scale paintings on canvas, and small works on wooden boards – which constitute one corpus, the sequel of an intensive work process that began in 2021 and continued almost until the exhibition’s opening. Hay Acco’s works await the viewers at the entrance to the gallery, accompanying them along the wall to the interior space, where over a thousand small works of varying dimensions are installed on wooden surfaces.

All the paintings portray amorphous images of different sizes, executed in a technique of engraving in tar, sometimes mixed with acrylic or ink. Each one simulates an intimate movement with and within itself, while a wild dynamic unfolds between the images.

The work of Dalia Hay Acco

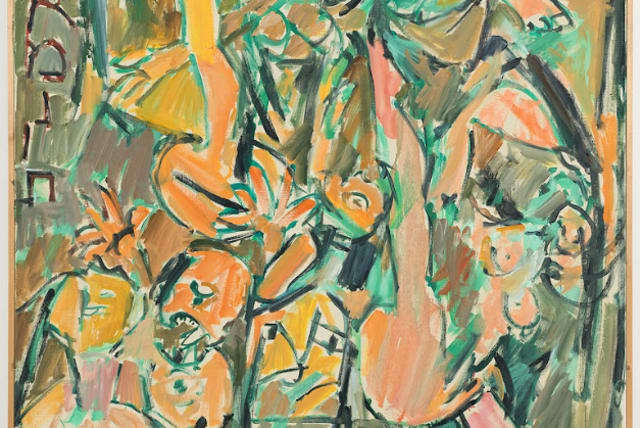

Hay Acco’s current work began in the 2021 exhibition “Luning” presented at the Tel Aviv Artists’ House. The works in that exhibition were created daily throughout an entire calendar year as a repetitive documentation of a self-portrait – moods, memories, thoughts, experiences, and events. Each work constituted a record of a different time, a different situation, a different state; the transition from one work to another seemed like gliding from time to time, from one state to another in her repetitious movement, day in and day out.

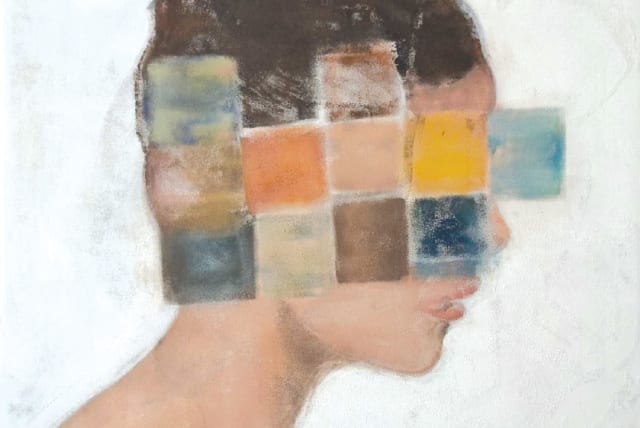

Since then, Hay Acco’s mother passed away, and the collective crisis faded into a personal crisis. The repetitious personal diary, which had an organizing dimension (one work a day for 365 days), collapsed into continued work under a new, chaotic, repetitious personal commandment, devoid of boundaries and time.

“The installation of these works is an attempt to contain a chaotic overabundance – like the shattering of intact images into particles, gaping them and looking into their interior – enabling a new revelation of reason and a new order,” says Drumer. “The engraving in tar and in black-gray-brown paints introduces a bestial survival instinct, a senseless movement of a primal drive, the screams of fragments.”

Hay Acco gives us access to an intimate private space of primary mental qualities: over a thousand variously sized works, spanning what appear to be trunks, branches, roots, snakes, arteries, pipes, wires, hairs, paths, roads, and routes, all of which can be perceived as different manifestations of the umbilical cord that connects mother and daughter, the cord to an ancient inner world, the nine-month world, the world of connection, primal bond, and physical symbiosis.

“I paint from the gut,” says Hay Acco. “I paint from the disintegration of the mother, from the death of something that enables me to paint, to represent, to convey its works through my hand, as my gaze is turned inward and the hand draws outward as if my hand were the umbilical cord – the cord of connection.” ■