Aviva Blum and Wojciech Ciesniewski are opposite sides of the same highly evocative coin. Blum is a 92-year-old Israeli survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto. Ciesniewski is a 66-year-old Polish painter and educator who feeds off Holocaust-related images to produce evocative oil paintings that send out emotional ripples down the corridors of time, from that seismic chapter in the Jewish timeline.

Remarkably, the two joined forces last year to collaborate in the “Life After All” exhibition at the Museum of Masovian Jews in Plock, housed in a former synagogue, some 110 km. west of Warsaw. Now the show is getting a reprise here and is due to run at the President Hotel Gallery in Jerusalem, May 2-June 13, under the auspices of the Polish foundation, Fundacja Wojciecha Ciesniewskiego. The Embassy of the Republic of Poland in Tel Aviv, POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Warsaw Ghetto Museum, and the Polish Institute Tel Aviv also support the project.

It is an unlikely synergy on all sorts of counts. For starters there is the plain fact that Blum spent her early formative years in the most trying of circumstances, somehow surviving by her wits and those of her elders, and the intervention of plain old Lady Luck. She and Ciesniewski, of course, belong to different generations and live in very different societies. They also employ contrasting stylistic vehicles of expression spawned by their disparate takes on translating their individual emotional baggage and philosophical outlook into visual form.

Understanding the Life After All exhibit

The title of the exhibition imparts something of an oxymoronic, if not contradictory, element. Blum, who lived in Jerusalem for 60 years before moving to Tel Aviv last year to be near her family, has said in various interviews over the years, that she paints in order to forget her traumatic childhood and youth in Poland. Meanwhile, Ciesniewski states unequivocally that he paints to try to keep alive the memory of those who perished and to honor those who survived, such as Blum.

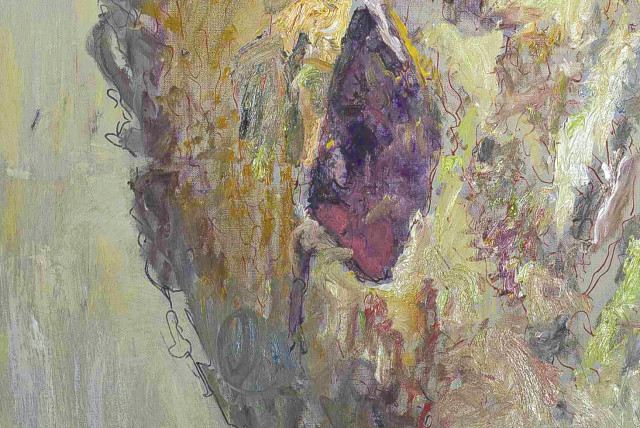

There is a similar yin-yang feel to the artists’ painting styles. Blum leans towards the abstract, notwithstanding the fact that the main theme of her January 2023 exhibition, at the Biennale Gallery in Jerusalem’s old Shaarei Zedek Hospital building, was the landscapes she viewed from her former residence in the capital. Ciesniewski’s style is far more visceral and tends towards the figurative.

Interestingly, the Polish painter, who teaches at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, has plenty of abstract output in the initial part of his oeuvre. He spent his youth and early adulthood under the constraints of communist rule, and he eventually gravitated towards the figurative with a view to making his paintings less ambiguous and more communicative. More recently, he has been turning to motifs taken from dramatic junctures of the 20th century, based on a desire to express solidarity with the victims of persecution and totalitarianism. A recurring theme in his work is the troubled history of his place of origin and his own family, playing out under the shadow of fascism and postwar communist reality.

Ciesniewski got his first inkling of his country’s dark Holocaust-related past as a teenager at school, and riding his bicycle through the countryside where he espied strange mounds which he later learned covered mass graves. “My curiosity about ‘what am I aware of?” began in the early 1970s by asking questions about the history of my hometown of Działdów, as well as its Masurian surroundings. The subject of Jews killed en masse in gas chambers and burned in crematoria at Auschwitz and Treblinka came up at school,” he recalls. “I identified the word ‘ghetto’ with the tragic fate of the entire Jewish people, their gruesome humiliation and imprisonment ending in death.”

The Holocaust was always there, lurking in the back of Ciesniewski’s mind, and he continued to research the topic and take on new information.

One particular image from the aftermath of that harrowing passage of time grabbed him so powerfully that he felt compelled to portray what he saw in his own singular way. “In the spring of 2022 I painted a motif of three teenage girls with beautiful pubescent shapes dressed in colorful dresses, sitting on a bench against a background of green trees,” he notes. “This motif came from a black-and-white photo on Yad Vashem’s Facebook page, and depicted the alumnae of the David Guzik Children’s Home in Otwock in 1948.”

Blum spent some time at the said institution which was run for a while by her mother Luba Bielicka Blum, a nurse by training who had saved a large number of Jewish children from being deported to extermination camps during the war. Chana Grynberg and Elvira Grossfeld were among Blum’s friends at the home and the threesome appeared in the online print that fired Ciesniewski’s imagination and inspired him to paint his own take on the setting.

“Life After All” is very much a tale of two artists, from definitively antithetical personal and cultural backdrops, who express themselves through contrasting visual idioms but who nonetheless converge at a critical intersection of thought and emotion.

Sadly, Ciesniewski’s drive to convey the suffering of victims of violence and tyranny has been refueled by the events of October 7, and his contribution to the exhibition in Jerusalem references that all-too-fresh cataclysmic episode. His exhibits here will include paintings called I Love You, My Son and Escape from the Darkness. There is also an image, called About the Threat, of 75-year-old Warsaw-born historian of Polish culture Alex Dancyg who was kidnapped from his home in Nir Oz on October 7 by Hamas terrorists and taken hostage to Gaza.

Dark and dismal source subject matter notwithstanding, Ciesniewski would very much like to engender a spirit of optimism and hope. He feels we need to take a balanced view of life and the forces that impact us.

“My paintings allude to themes of both good and evil,” he says. “Their messages are meant to express my intentions: to create in the viewer a feeling, and thoughts, of the beauty of life itself.” In these troubled times, that is a message we would do well to imbibe and implement.

The President Hotel Gallery is open Sun.-Thu., 10 a.m.-10 p.m., Fri., 10 a.m.-1 p.m.