Requiems tend to deliver stirring listening experiences. The eulogistic work written by 20th-century French composer and organist Maurice Duruflé certainly gets the emotions going.

His Requiem partners Mass in G by compatriot contemporary composer and pianist Francis Poulenc in a program to be performed by the Israeli Vocal Ensemble (IVE) in its forthcoming nationwide tour, which kicks off at the Scottish Church in Jerusalem on May 31 (11 a.m.).

The circuit also includes concerts in Haifa, Ra’anana, and Tel Aviv. The finale at the Tel Aviv Museum on June 4 (8:30 p.m.) will also be available via streaming on the ensemble’s web site.

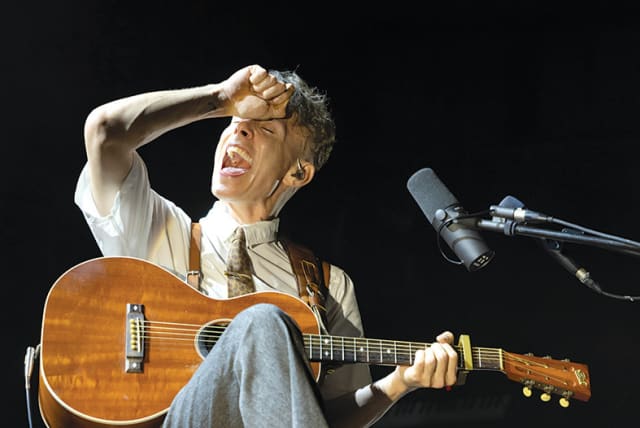

Boris Zobin is excited, and somewhat daunted, by the prospect of playing the organ in the French choral music concert series, under the baton of IVE founder, music director, and conductor Yuval Benozer. The vocal solo spots are taken by soprano Tom Ben Ishai and bass singer Alexey Kanunikov.

The 48-year-old Soviet-born keyboardist has paid his dues on the instrument, in various guises and of varying dimensions, all over the world. The organ is a special animal which, more often than not, demands not only high-level musicianship. The player also has to be nimble with their hands as they find their way around one or more keyboards, in addition to plying a sure course across the foot pedals – not to mention the manually operated stops that change the texture of the sonic output.

That assignment becomes even more challenging when the work you are performing requires particularly well-honed skills and advanced musical intelligence. “The role of the organ is very difficult to do, and do it well,” Zobin states. “In normal circumstances, there would be an orchestra (for the Duruflé composition). The composer himself wrote it for an organ but, in order to fill the place of an orchestra he made it a very virtuosic part.”

It is not just a matter of – literally and metaphorically – pulling out the stops to do the organ part justice. “There are lots of places where there is dialogue (as it were) between different orchestral instruments, and I have to make sure I get that in,” Zobin continues.

Dexterity and fleetness of limbs are the order of the day. “There are places where I have to play on two keyboards simultaneously with one hand. It is very technical. A pianist just plays the piano and enjoys the music. But I have to think about several things at the same time – which hand to use on which keyboard, and in which register. You need good coordination. You need to be good at multitasking – super-multitasking,” he chuckles.

The story of the Requiem

SOUNDS LIKE quite a workout but the end product should be well worth the effort. Zobin admits to taking his time to take the Requiem into his heart. Considering the work’s enduring popularity around the globe, it comes as some surprise to hear this will only be Zobin’s second stab at it.

“I have to say that, when I began to study the work, I didn’t really connect with it. But, as I practiced and listened to different renditions of it, and read up about the Requiem, I eventually realized how great it is. And this is an early work of his. That is amazing.”

In fact, the Requiem was completed in 1947 – intriguingly, originally commissioned by the Nazi collaborationist Vichy regime in the south of France. Duruflé was originally tasked with writing a symphonic poem but ended up with the Requiem. It appears as Opus 9 in his body of work, although it was completed some 20 years after Duruflé’s debut as a composer, a solo piece for organ published in 1926.

The technical logistics Zobin has to cope with means he had to put the hours in the practice room. “You have to get to a point whereby you play it like an automat. This work requires a lot of practice,” he notes. That must be as trying as it is rewarding and, says Zobin, it is well worth the effort.

He says there are cultural gains to be enjoyed, and an abundance of treasures yet to be discovered and delivered for the public’s benefit. “The whole French musical school of thought is very interesting in relation to the organ. People think that the organ equates to Bach only. There is a French romantic musical school and special organs built by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll [in the 19th century]. He built symphonic organs that could take the place of an orchestra, a large orchestra playing romantic music.” Sounds like just the ticket for the Duruflé run.

That spawned a flurry of compositional offerings by the likes of romantic composer César Franck and, later, Alexandre Guilmant, Louis Verne, and Marcel Dupré.

“They wrote amazing works for the organ,” says Zobin. “They also wrote symphonies for the organ. [Late Romantic Era composer-organist Charles-Marie] Widor has organ symphonies. And Guilmant wrote sonatas for the organ.” Zobin clearly has some heritage to draw on for his IVE venture.

Over the years, Zobin has had opportunities to try his hand on all sorts of organs, including a monster in a church in Riga, Latvia. As befitting his generation, he has kept pace with technological developments and says his electric organ at home is designed to replicate the sound of a mechanical instrument with giant towering pipes.

“There is always a small percentage of the pipes that are not precisely tuned,” he explains. That is duly taken into account in an effort to reproduce the real McCoy. “I have a button on my electronic organ that reproduces that sound, of pipes that are not fully tuned.”

Zobin may be happy to get a big “real” sound out of his electronic instrument but he is wary of taking technology too far. With the proliferation of AI-created art some say that, for example, Spotify will soon not have any music written by human composers. “Yes, they are trying to create a composer who writes exactly like Bach,” he says with a sigh.

That is not a comforting thought but, for now at least, we can revel in the sounds on offer from the thoroughly human member of the IVE.

Not bad for starters.

For tickets and more information: (074) 701-2112 and ivocal.co.il/en