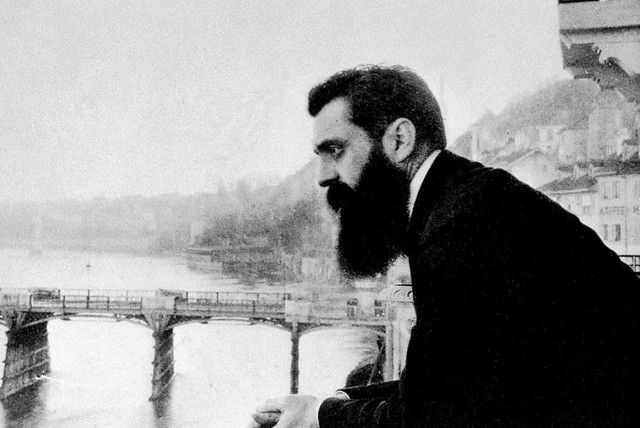

Like an ink drop splotched on blank paper, a grim Herzl (Oded Reich), with black beard, hat, and coat, grasped at his younger self, Theodor (Noam Heinz), clean-shaven and dressed in white.

“Nothing is more important than opera!” the younger man said after listening to Wagner. “The opera is a dying world,” the same man, now older, told the patrons watching Theodor at the Israeli Opera.

“They are out there, the hate-filled people,” he said, “you,” dear audience, “are a footnote.”

Roughly three years in the making, the opera adaptation of key moments in the life of the founding father of Zionism, Theodor Herzl, and how he turned from a highly assimilated German-speaking Jew to a modern Moses-like figure, was a roaring success. A bonus performance had already been added.

Visually, Theodor’s set and costume designers, Alexander Lisianski and Oren Dar, respectively, have done a formidable job in expressing the mirrored nature of the drama on stage.

The dark shades of Paris in winter, when the whole of France was driven mad during the Dreyfus affair and angry mobs called out for Jewish blood, is transformed to the warm hues of a tavern set in an idyllic forest. In this jovial setting, beer serving maids offered select Jews – highly assimilated Jews – a chance to join a brotherhood, to become so-called real Germans.

The dual tragedy of Theodor, that of the young man and his older self, is how both promises turned to dross under the harsh sunlight of reality. The French promise of equal civic rights to Jews soured after Dreyfus. The German promise of loving brotherhood proved false when Wagner began to spew his ideas about the corroding influence Jews have on Germans. On stage, Reich, as Herzl, uses his lanky frame to offer us the illusion he is running in the endless streets of Paris, panged by something that he cannot yet name.

Reich is gifted with an excellent cast to work with. Among the key roles are his friend Paul von Portheim (Shaked Strul), a Jewish friend who wished to join the German fraternity; a priest (Tamara Navoth), who offered the false promise of conversion; and a knave (Yuri Kissin) who offered the tormented man a visit to a Pigalle brothel (Herzl vomits when he sees what lurks inside).

The Latin-infused mass scene, with Navoth offering salvation one moment with Kyrie eléison [God have Mercy], and punishment the next with Dies iræ [Day of Wrath] is a stunning interplay between intimate familiarity with the Christian roots of Western music, opera included, and Jewish irony as Reich bends forward and backward, away from the offered cross.

An artistic portrayal of history

STRUL USED her smaller frame in a masterful, emotionally heartbreaking suicide scene during which she gifted us with the sensation her character is a lost child. Kissin is a wonderful villain, down to his sinister twirling of his blond mustache before he exited the stage.

The historical Herzl did not only flee from French and German promises of acceptance to a grand vision of a Jewish State. He also fled an unhappy marriage, a painful failure to be a father, and perhaps the demand to feed the ever-hungry press of Neue Freie Presse, for which he covered the Dreyfus affair to begin with.

In the role of Julie Herzl, his wife, is the stunning Anat Czarny. Czarny brought the house down after her grand performance as the long suffering wife of a dreamer.

“Thus spoke Theodor,” she spat, “kiss the cross because Herzl said.” This, in reference to an early idea her husband had, that the Jews would convert to Christianity.

A religion thousands of years old, Czarny pointed out, cannot end because one man said it ought to.

Ours is an age which looks to the past, the imaginary as well as the research-based one, and seeks answers. In the US, Hamilton touched on very similar themes to Theodor. Who were the founding fathers, really? Can we still look up to them? We live in a land they shaped – do we like this shape or do we alter it?

One major difference, perhaps, between the American production and the Israeli one is this. In the production I saw, the audience clapped long and hard when Herzl proclaimed the Jewish state would protect the non-Jews living in it.

Seeing as the premiere took place on Wednesday, May 10, when Operation Shield and Arrow was still in progress, bombs were dropped on some non-Jews who live a one hour car ride away from the opera house while these lofty words were sung.

It is likely those who cheered these words would point out ideals, among them US democracy, are worthy of our support even when we know we fall short of upholding them. Even when, like Herzl, we grasp at our younger versions and never quite make contact.

“Write, write,” the young Theodor tells Herzl, “I’m writing, I’m writing” the older man replies. This is a quote lifted from Shlomo Artzi’s 1988 hit July August Heat. In this rock song, the singer says more things. “Write a page in your book,” he sings, “we are discussing wars. I go dancing with dead soldiers in my heart.”

Theodor, sung in Hebrew with English titles, will go on stage for the last time this season on Monday, May 22, at 8 p.m. Tickets range from NIS 195 to NIS 445, depending on the seats. The Israeli Opera is at 19 Shaul Hamelech St. For more information, contact (03) 692-7777.