Israel needs films about Irgun, Lehi fighting the British - opinion

Why does the history of the Irgun and Lehi have such a poor record of cinema and television treatment?

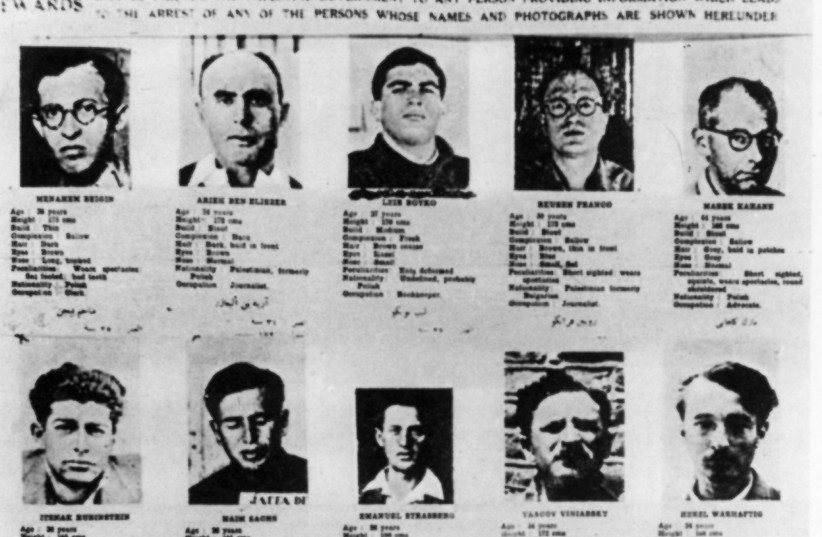

The British Mandatory authorities, under an increasing onslaught by fighters of the Hebrew underground resistance against their rule, renewed at the beginning of 1944, launched Operation Snowball on October 19, 1944, quickly, efficiently and with surprise.

Confronted with several successful and attempted escapes of Irgun and Lehi prisoners, the high commissioner authorized a radical solution: forced exile. A total of 251 detainees, including 12 from Acre Prison who were being held for security offenses at the Latrun Camp, were removed from their beds before dawn and then, in short order, flown out to Asmara, the capital of Eritrea. The next day, they were trucked a few kilometers south from the airfield to the Sembel Camp.

On January 21, 1945, three days after internees Benyamin Zeroni, Haggai Lev and Shimon Sheba escaped, only to be caught shortly after at a British checkpoint when on a bus traveling to the border, all were taken from Sembel to Massawa port, over 100 km. to the northeast. There they were put aboard an Italian vessel and under severe conditions transferred to Carthage, in Sudan. They remained there until October 9, 1945.

The camp was 600 km. from the nearest hospital at Khartoum and in a hot desert with trucked-in water supplies. Nevertheless, five prisoners escaped and made their way 160 km. to Port Sudan via Asmara. There, their plans went awry and they were rearrested while attempting to travel to Khartoum.

Two later escapes (there were eight altogether) were most probably the longest in distance in history. One was from the Gilgil Camp in Kenya. Upon exiting a tunnel, a prearranged ride took them to Uganda and from there to the Belgian Congo, where they flew to Brussels. Another was from Sembel to Asmara to Addis Ababa to Djibouti and then to France. All the remaining detainees were only repatriated to the nascent State of Israel in July 1948, although Moshe Sharett did not rule out the option of arresting them immediately upon arrival, fearing that they might subvert the government.

By all accounts, this almost four-year period was one of suffering and a great challenge to the men’s physical and psychological fortitude. They overcame the harshness of the conditions and the British attitude toward severe restrictions. Three of them died, two being shot by guards during a demonstration and one due to inadequate medical attention.

They created education programs (Supreme Court president Meir Shamgar and justice minister Shmuel Tamir received their first law degree there via mail). Theater and other cultural activities were maintained and they even succeeded in having kosher food provided with a slaughterer sent from Palestine. For those who recall The Great Escape starring Steve McQueen, Richard Attenborough, Charles Bronson and James Coburn, this episode should have been worthy of a cinema screen treatment decades ago.

Why was the Irgun and Lehi history not faithfully adapted?

YET WE were forced to wait until this past December to view the KAN broadcaster’s production on the theme. With the brothers Reshef Levi and Yannets Levi, together with Regev Levy, in charge of a reported $20 million (NIS 67.4 m.) production, a summary reads: “Elijah Levi, a successful comedian in 1942 Palestine, is deported by the British authorities to Carthago, a detainee camp, in which he is held with Jewish underground warriors and Nazi criminals.”

The opening credits of the first episode said: “Based on a true story.” Yet despite using the names Irgun and Lehi and, of course, Carthago, almost nothing in the unfolding script was true nor authentic. It became apparent that this was a mishmash of history. Some thought that possibly the Levi brothers were taking revenge for the way their father, Yitzhak, himself a Lehi member and a detainee, was treated by his fellow prisoners.

While The Jerusalem Post’s Greer Fay Cashman has termed it an “improbable situation” (January 4), it was more an impossible one. Nazi and Italian soldiers were never held together with Jews. Drug running was not part of the situation. As the series proceeded, the script became more and more bizarre.

Following protests – especially by children of fighters who spent years in African exile, such as Limor Livnat, herself a former MK and minister; Dan Meridor, former justice minister and son of Knesset member Eliyahu Meridor; Shlomo Tzipori whose father, Mordechai, was an MK and a minister; Ram Shamgar, son of Meir Shamgar, the former president of the Supreme Court; Rachel Kremerman, daughter of Ya’akov Meridor; and Ido Nechushtan, former chief of Israel’s Air Force – the credit was altered.

It now informs viewers that the series is an imagined drama and was inspired by historical events. Moreover, it states that portions of the events, locations, characters and dialogues were altered and concocted for dramatic effect, and that any resemblance to the true characters and happenings is coincidental. If it is any consolation, the leading female persona who has an affair with the prisoner Eliyahu Levi in the camp, French actress Carolina Jurczak, was born to Polish Jewish parents.

The real issue, however, is why does the history of the Irgun and Lehi have such a poor record of cinema and television treatment? Otto Preminger’s Exodus has the Acre Prison breakout performed not by the Irgun but by the Hagana. Avi Nesher’s 1984 film Rage and Glory was more of an authentic portrayal, despite the over-the-top brutality of the main character, a Lehi assassin.

Back in 2008, Channel Two television broadcast a series, directed by Eli Cohen, on the Altalena incident. It notably had Menachem Begin walking among the fatalities on the beach while holding an umbrella. The script was by Motti Lerner, who also wrote the docudrama on Sarah Aaronsohn, which required a High Court of Justice intervention.

In 1994, Lerner was involved, again, in another controversy over his series on Hannah Szenes in Kastner. It would appear that there was not much diversity in selecting scriptwriters either.

One dramatic series that was relatively successful, being sold to Netflix, was Kan’s The Beauty Queen of Jerusalem, which includes a minor involvement of the Irgun.

AS MUCH as it is a matter of the pre-state political rivalry, there is an important ramification on the cultural legacy contest between the camps. What is apparent is that successful attempts have been made to control the collective social memory of Israel’s Zionist history in a continued and consistent process. This, in turn, has provided a cultural elite, through the instrument of entertainment, to possess an outsized and disproportionate amount of hierarchy power.

As British social anthropologist Paul J. Connerton has noted, in presenting to the public edited images and reworked dialogue, those producing these series have a legitimating effect of a narrative of the past as well as serving very specific social and political order.

As he wrote in his 1989 How Societies Remember, the “images of the past and recollected knowledge of the past are conveyed and sustained by ritual performances.” The images of the past are recollected knowledge which then becomes the national myth.

If the absolute dominance of a major purveyor of a nation’s history for the masses lacks factual credibility, as well as being produced by a narrow group of politically prejudiced elitists, we are victims of the propaganda of persuasive entertainment. In a 2011 interview, Connerton spoke of a cultural memory that can be reappropriated.

While Connerton warned of a process of coerced forgetting, I would suggest that the history of Zionism, in general, and that of the other Zionists, those of the Revisionist wing and the Jabotinsky camp, have been subjected to an additional process of manipulative rewrite. The role of television and film in the construction of history and its reconstruction is critical in the maintenance of cultural power, a major pillar of support for a certain political regime.

Israel’s theaters, television studios and movie sets have been quite successful in bringing us the stories of the Second Aliyah pioneers, illegal immigrants, Palmah fighters and the kibbutz founders. It is about time that an equal amount of talent and professional ability is devoted to tales of past heroism of the armed struggle for Jewish liberation, whether pasting up posters, attacking British installations, escaping from detention camps, or ascending to the gallows.

This history is part of Israel’s legacy and needs to be part of our collective memory.

The writer is an analyst and an opinion commentator on political, cultural and media issues.

Jerusalem Post Store

`; document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont; var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link"); if (divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined') { divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e"; divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center"; divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "15px"; divWithLink.style.marginTop = "15px"; divWithLink.style.width = "100%"; divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#122952"; divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff"; divWithLink.style.lineHeight = "1.5"; } } (function (v, i) { });