Camel spiders' hidden evolutionary tree uncovered by Israeli researchers

They aren’t spiders and don’t bug dromedaries, but a scorpion that existed before the disappearance of dinosaurs.

The “camel spider” has nothing to do with dromedaries; they aren’t even bugs attracted to their humps. Often referred to as “neglected arachnid cousins,” or “wind scorpions,” camel spiders are not even spiders but a type of ginger-colored scorpion that has long been a subject of fascination due to their remarkable features such as aggression, exceptional running speed, and adaptation to arid environments.

Known to scientists as solifugae, they are predators and carnivores that move very quickly and swiftly, reaching 16 kilometers per hour. These arachnids have very strong jaws and may bite if they feel threatened but are not poisonous. Found in areas with dry climates throughout the world including the Middle East, Mexico, and the southwestern US, they have a lifespan of about a year and are very difficult to raise in captivity.

Despite their notoriety, the lack of a higher-level phylogeny (molecular evolutionary tree) has left many questions unanswered about how these intriguing creatures developed.

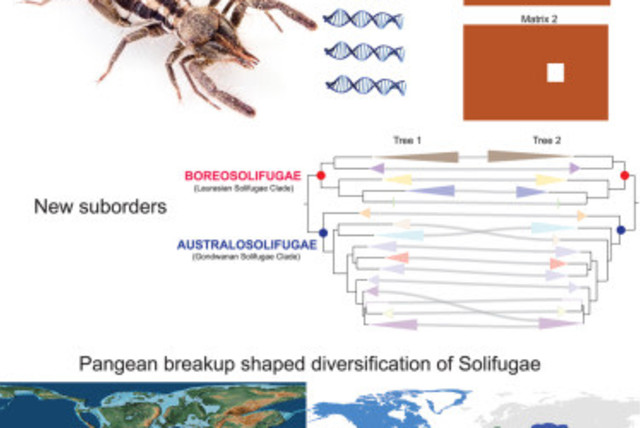

Now, a new study has been published in the journal iScience under the title “Neglected no longer: Phylogenomic resolution of higher-level relationships in Solifugae.” Led by the labs of Prof. Prashant Sharma of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Dr. Efrat Gavish-Regev of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU), the team members have unveiled the long-standing mysteries surrounding these arachnids. This pioneering research marks a major milestone by establishing the very first comprehensive molecular tree, or phylogeny, of this enigmatic arachnid order, shedding light on their evolutionary history and relationships.

By harnessing advanced sequencing technologies and a unique genetic dataset, the study has overcome past difficulties in distinguishing and understanding the evolution of these amazing creatures. The research not only reclassifies camel spiders into two new groups but also highlights the significance of modern genomic techniques in uncovering the secrets of enigmatic organisms, ultimately deepening our appreciation for biodiversity and evolutionary science.

Their first-ever comprehensive molecular tree of this enigmatic arachnid order was based on advanced sequencing technologies and a novel dataset. In the past, it was hard to study camel spiders because we couldn't easily tell them apart based on their phenotype. Until recently, the phylogeny of only one family out of the 12 recent families of camel spiders was studied using their genes that carry information, mainly because many historical specimens have been stored for decades in collections around the world under conditions that were damaging their DNA, and made it useless for genomic study.

But now, Sharma, Gavish-Regev, and their collaborators have used advanced techniques to look at specific parts of the genome that are preserved in all camel spiders and the regions around them that had been changed during evolution. Spearheaded by Dr. Siddharth Kulkarni, a postdoctoral researcher in Madison, the novel method they used can also take advantage of historical material and leverage fragmented DNA for genetic analysis. This allowed them to learn more about all the different families of camel spiders and their relationships with each other.

Are they found in America?

They discovered that there are two main groups of camel spiders in the Americas – part of a bigger group of camel spiders that started evolving in tropical regions a long time ago. By looking at ancient evidence like fossils, they figured out that the scorpions began evolving around 250 to 300 million years ago during the Permian period. Most of these families were already different from each other before a major extinction event around 66 million years ago, which is when many species, including the dinosaurs, disappeared. This suggests that the breakup of continents had a big impact on how camel spiders evolved.

Gavish-Regev said she was very excited about their findings because “our work has finally brought camel spiders out of the shadows and into the light of phylogenomic analysis. We now have a better picture of their evolutionary history and relationships, and our proposed suborders provide a solid framework for future research in this fascinating field. It will further stimulate research into Solifugae and deepen our appreciation for the biodiversity of our planet.”