Despite all the ever-rapidly advancing development of new technologies, pharmaceutical products, surgical intervention and even all sorts of nature-based market offerings, there is no stopping time. The bare, inescapable fact of the matter is we grow older and take on the physical and, sometimes, neurological fallout thereof. As a sagacious person or two have noted soberly, there is only one alternative to getting older. Jam-packed cemeteries are stone-cold evidence of that.

However, while we are still around, we can – and, more often than not, do – suppress episodes in our past that we don’t wish to engage in. That can, for example, be Holocaust-generated trauma or any other kind of troubling baggage we pick up along the way.

Rina Peled has no desire to paper over those cracks.

“There is nothing really perfect,” she states. “And, anyway, that isn’t even interesting. What is interesting is looking at the flaws.”

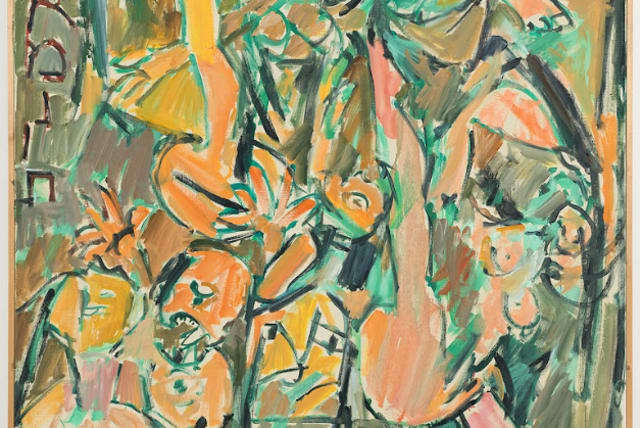

That is exactly what she did in creating the works that compose her current exhibition at the Agripas 12 Gallery, down the road from the shuk. The show, curated by Nava Barazani, goes by the name of “The Golden Bond,” which basically gives the game away. While some may identify that with a certain secret agent 007, Peled’s predilection for the precious metal follows a creative, remedial and restorative line.

The Golden Bond exhibit

The 15 or so works on the pristine whitewashed walls at the gallery’s cozy backstreet premises exude an attractively oxymoronic sense of rags and riches. The substratum for Peled’s abstract oil paintings comes from the grimier, more elemental side of everyday life. She opted for wood rather than canvas.

“That happened by chance,” she recalls, although quickly agreeing with my observation that, at the end of the day, nothing really happens as the result of coincidence. Things occur, as and when they do. That may sound simplistic, but it is a fact of life.

“One day I was at home and I wanted to paint, but I’d run out of canvases,” Peled explains. She found a creative solution to the problem, something along the lines of the notorious suggestion attributed to Marie Antoinette. On being told her penurious pre-French Revolution subjects did not have any bread to eat, she is said to have commented that they could eat cake instead.

“I thought, if I don’t have canvas, I’ll try to paint on slabs of wood,” she says. It was an epiphanous moment in her working life. “I discovered that wood is far more suitable for me than canvas. I can abuse it, Peled adds with utter seriousness.

Although there are no glaring signs of destruction and chaos in the exhibition, that feral approach is evident in all the works at the gallery.

“Look here. I scraped away at the wood and I filled it with paint,” she says as she draws my attention to a modestly proportioned painting with a fetching fusion of bluish shades subtly balanced by delicate streaks that tend toward orange.

SHE EXPENDED a considerable amount of energy on the paintings. “I scratch the wood and use a scraper. I chisel into them. I paint layer upon layer.”

That was a bit of a giveaway which goes a long way toward explaining the lustrous arterial elements in the pictures. Around a year or so ago Peled learned from a friend about the Japanese preservation technique called kintsugi. The term translates as “golden joinery” and refers to the Japanese art of piecing together broken pottery by mending the areas of breakage with lacquer dusted or mixed with powdered gold. Silver and platinum can also be used.

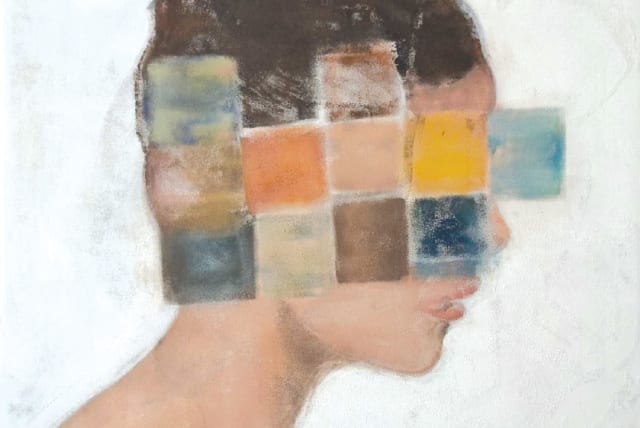

The above enlightening friend is Olga Negnevitsky, who guests in “The Golden Bond” with three works – a couple of multidisciplinary amalgams of photography, tapestry, painting and string, and a triad of kintsugi-treated objects.

“Olga works in restoration and repair of all sorts of ancient artifacts,” Peled says. “One day I went to visit her, and I saw she was repairing broken pottery with gold. She told me it was kintsugi.”

That is more than just an aesthetic approach. If we can, for a moment, put this into the context of the pockmarks of life and how they emerge in our corporeal beings in the cold light of day, kintsugi is the complete opposite of indulging in plastic surgery. Instead of, say, having our aging, sagging eyelids lifted by expensive surgical means we could apply brightly colored makeup. That would not, presumably, do much for our chances of landing a slot as a TV talk show host, but it might send out a signal that the facial “failings” are actually a simple sign of the times, and that we are not overly concerned about showing the world the inevitable ravages that come with advancing years.

Some of the fissures and lines in Peled’s pieces of wood have been duly filled and highlighted with gold paint, thereby drawing our attention to the blemishes rather than giving them a cosmetic makeover pretending they never existed.

But, as most artists will – should – tell you, the story we relate today is necessarily the product of our accrued life experience and, no doubt, some hereditary stuff, too.

“This is wabi-sabi,” she suggests, citing another area of traditional Japanese thought, which perceives life through the acceptance of transience and imperfection.

That is what excites Peled. “I love finding peeling walls and decay,” she says. “There is so much in those narratives, like at Alliance House,” she says with a nod to the late-19th-century structure near the shuk which still serves as a temporary shelter for a raft of cultural ventures.

She then shows me a picture she created based on a rough mesh spot in a building site across the road from the gallery.

“I love looking at building sites, at the various stages of new construction and at places that are deteriorating.”

If that is the case, these days Jerusalem must be an inexhaustible rich seam of inspiration for her as it continues to make the transition to a soaring brave new world of tower blocks of apartments and offices.

For Peled, painting is not just a way of creating a pleasing, thought-provoking and/or eye-catching bottom line. She attaches great importance not only to the process but also to conveying some idea of the evolving story line, as the material in question harbors a fascinating subtext.

“I learned more about kintsugi and I thought that, like the Japanese, instead of throwing out a broken utensil or vessel, maybe I should add to it. You don’t blur the breaks. I thought I would highlight some of the breaks with gold.”

THAT TIES in nicely with another area of interest.

“I am a historian,” Peled explains. “I have a particular interest in the fin de siècle period [at the end of the 19th century]. That was such a dynamic, wonderfully creative time.”

She says she has also been fascinated by the Holocaust since a very early age. “When I was a young kid, I began reading anything and everything I could about the Holocaust. I don’t know why. My parents came here as children, from Kurdistan. I have no direct connection with it.”

Perhaps some psychologist can shed light on that intriguing tendency. Be that as it may, that interest in our bio backdrop informs Peled’s work as an artist.

“Everything in our past informs who we are today,” she notes. “I think it is important to show that, to show the underlying strata in my paintings.”

The works make for fascinating viewing, particularly from close up. You note the free-flowing layering, the gashes Peled imposed on the pieces of wood, and the odd extraneous textural element, such as a small warp and weft item, and threaded cord. The latter was, perhaps, a seemingly clear reference to the work of a surgeon completing a repair job on a human body with stitches. Peled says the netting addendum offers a viewfinder glimpse of the physical and, necessarily, emotional underpinning of the surface end result. “This is a piece of fabric which is affixed to the wood, and shows the breaks and cracks underneath.”

Peled reprises an earlier theme. “That comes from wabi-sabi, which believes that beauty does not come from perfection. On the contrary, it comes from the absence of perfection.” Perhaps there is an important life lesson in there for us all. “I find the beauty in the imperfect,” she adds somewhat superfluously. “Kintsugi, the aesthetic of the imperfect, speaks to me a lot.”

That is also patently front and center in Negnevitsky’s fabric work. “This is a French tapestry from the 18th century,” Peled advises. “Olga repaired some of the tears with gold leaf.” It is a beautiful work, with a rich spread of hues, textures and shapes, which bridges the broad temporal divide without blurring the chronological chasm. There is also an alluring textural balance between the fragile and soft, and more rough-and-ready areas.

Peled likes the idea of transparency and transition.

“When you have something you can see through, it is like having a showcase cabinet, through which you see a piece of jewelry,” she says. That concept is heightened by the fact that Peled’s see-through components infer hidden nether strata, thereby getting us to make some effort and drawing us into the work in question.

The overriding chromatic impression one gets from “The Golden Bond” is one of nuanced, tranquil shades that run the modest gamut between black and gray to subtle variations on blue. That relatively narrow hue spread provides a charmingly handsome foundation from which streaks of gold twinkle and, as our eyes become attuned to the contextual surroundings, shine through in their unapologetic reflection of the consumer societally perceived defects.

ALMOST ALL of Peled’s works are on the decidedly small side. That adds to their charm, and Barazani has done a good job of grouping them in such a way as to leave oceans of white wall around them, thereby making the slimline palette range stand out all the more appealing.

There is one seemingly incongruous exhibit to one side of the main room, a wood triptych on a separate stand.

“When Nava [Barazani] came over to my house to choose works for the exhibition, she said this had to be in it, too,” Peled recalls. “I told her it was made separately, not in the past year like the rest of the paintings, and that it wasn’t connected to the others. She said it was, and that the background gold color tied it in with the kintsugi parts.”

The three-parter shows an evocative scene which looks like a landscape of singed trees with ash on the ground. “This comes from an exhibition I had in 2013, with paintings inspired by a burnt forest I saw.”

That immediately put me in mind, once again, of the Holocaust, but also of new life rising from the ashes. Yet another yin-yang pairing in a fascinating show. ❖

‘The Golden Bond’ closes on April 22. agripas12gallery.com