Among the broadening plethora of cultural institutions grinding back to beneficial operational life, it is particularly pleasing to see the Jerusalem Artists’ House reopen its standing rollout for our visual and sensory pleasure.

The six exhibitions were initially unveiled in early September but were summarily curtailed by the conflict raging on down south. Thankfully, director Ruth Zadka made the decision to jump on the bandwagon and join other cultural outlets here and across the country in offering us some respite from the ongoing emotional and existential doom and gloom.

One thing that has stood out in all the years I have been visiting, and covering, collections displayed at the venerable Ottoman structure on Shmuel Hanagid Street is an uncanny sense of a common denominator between the ostensibly disparate component parts on show on all three floors. Zadka says she is at a loss to understand why an unplanned conceptual core constantly emerges. “I don’t know why that happens,” she smiles. “It’s strange.”

That may be a little surreal, but it adds an endearing quality to the viewing experience as one accrues an evolving feeling of familiarity and ingests a philosophical and aesthetic continuum that runs through the swath of works by different artists – currently by half a dozen practitioners of various disciplines, styles, and approaches to visual renderings of individual emotional and corporeal baggage.

It is, perhaps, easy to get the ethereal, yet palpable, line that connects, for example, the niftily titled Matter of Time layout on the ground floor with Yam Amrani’s assemblage of outsized paintings on the top level. For starters, there is the polychromic presentation which, in the latter’s case, amounts to a veritable explosion of shades and shapes. The communal thread is also evident between paintings and drawings created by Sara Benninga and Yael Boverman-Attas, who, along with photographer Noga Greenberg, are established artists that comprise a triad of new members of the Jerusalem Artists Association. Curator Meydad Eliyahu underlines the existence of a thematic interface, albeit of a subliminal nature, by positioning one of Boverman-Attas’s sketches – the largest of her contingent – in the same display area as Benninga’s generously dimensioned canvases.

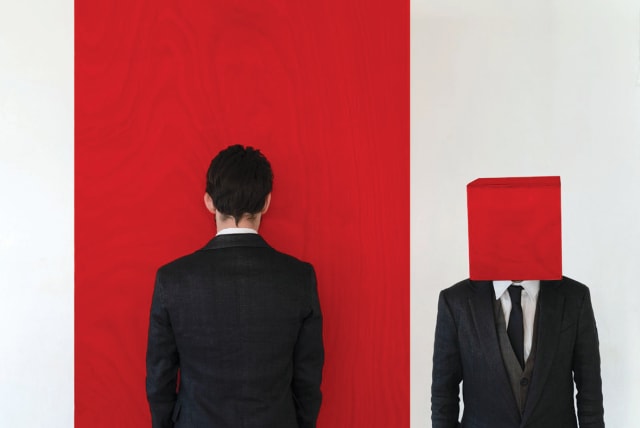

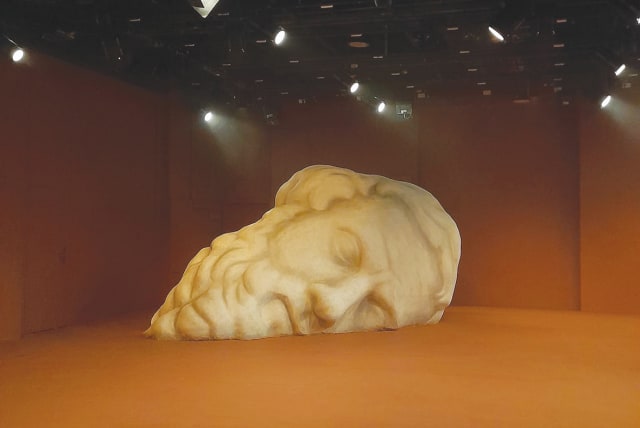

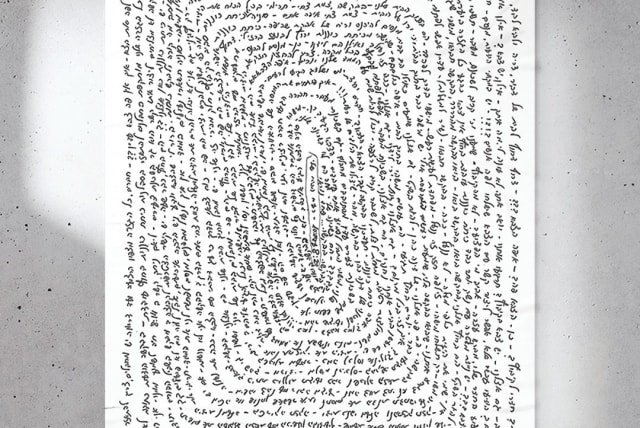

The starter to the Artists’ House offering is the most technologically oriented and, possibly by dint of the virtual format, the most difficult to fathom. Then again, Eden Bezalel Habas, an honors graduate of the department of Screen-Based Arts at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, is very much rooted in the corporeal, too. That comes across in the show moniker which, Bezalel Habas explains, comprises numerous subtexts that we are at liberty to interpret as we wish. “Matter is also substance,” he says with an impish smile, suggesting an oxymoronic complement to his three-screen installation. “And time can refer to an era, and also timing – the moment when something occurs.”

The yin-yang pendulum balance and ebb-and-flow dynamic are central to the spread. Even as someone who grew up in the Internet-facilitated – or Internet-compromised – era or, possibly, due to that very fact, Bezalel Habas is keenly aware of the importance of maintaining a firm grasp on what Mother Nature puts out there. But it all filters through the physically and sensorially mitigating screen medium, as befitting an experiential zeitgeist which has us all glued to our cell phones or computer screens for our information and visual kicks. The video works duly examine the way reality is reflected through the screens that constantly surround us.

Indeed, on many an occasion I have spotted someone taking photos of, say, a particularly impressive sunset instead of simply watching it and marveling. It is as if we feel that if we don’t snap something, we weren’t there, while the opposite is probably nearer to the truth.

That can spawn a situation in which the tangible is not necessarily given the attention it deserves, and we need some prompting to get us to take something on board, fully consciously. “In the current era, where an incessant flow of images and multiple screens have become the ‘natural’ environment, the aesthetic expression of the information revolution cannot be contained,” notes curator Efrat Shalem. “In his first solo exhibition, Bezalel Habas sets out to explore the crisis of trust between the viewer and the screen,” she adds.

The artist gets us thinking by piping the footage of natural phenomena through left-field formats. One of the big screens is set on a whacky angle on the wall, while all three show images of nature – sea waves, vegetation, and clouds – through a manipulated processed prism.

“The screens in the video works appear futuristic and primitive at the same time, as if telling us about what was or what is to come,” says Salem. Bezalel Habas is clearly not sold on the idea of technological advancements and how they impact on our quotidian cognizance. Personally, as someone who grew up in pre-home computer times, let alone cellphones, I take encouragement from that.

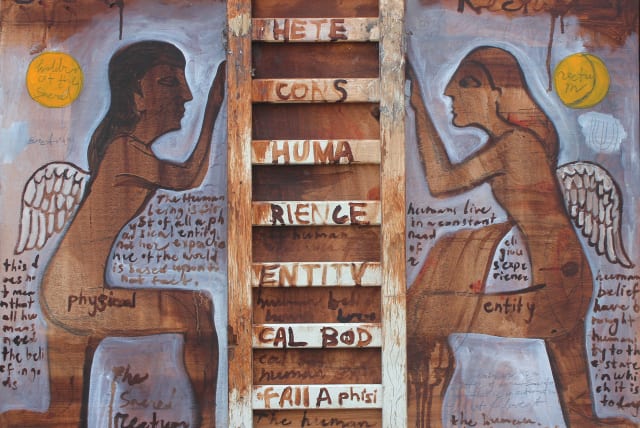

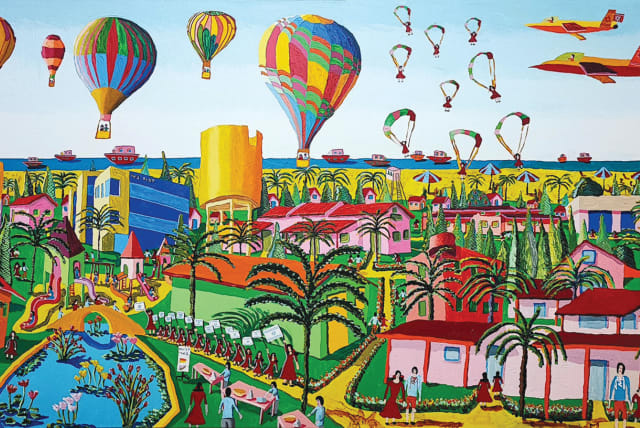

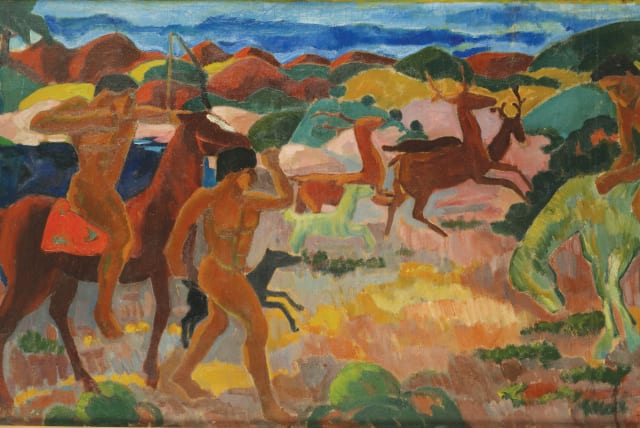

Amrani’s spread on the top floor is an entirely different kettle of fish, although no less strikingly and richly chromic. His canvases are expansive and imposing, but not in an invasive or intrusive way. There is also a lot going on in his creations, but one is intrigued by the dynamics, rather than overwhelmed by them, and drawn to explore figures, forms, and relationships that gradually leave their mark on your consciousness.

About Amrani and Benninga

Amrani clearly has a lot going for him. His show is courtesy of receiving the prestigious 2023 Osnat Mozes Painting Prize for a Young Artist, which is awarded annually to rising talents in the under-35 age group. That’s not a bad feather to pop into his incipient creative hat, and judging by the current display, it is well deserved. There is a lot to see, and discern, in his paintings that seamlessly straddle the generally considered antipodal spheres of abstract and figurative painting. Amrani seems to accommodate all of that. It all flows so naturally in his work and provides for an alluring and curious cerebral and emotional affair.

His work loosely follows a deconstructive and reconstructive continuum, based on abstraction of complex images, primarily referencing the organic body. By means of collage, he fuses these images with a wide spectrum of pictorial gestures to create a range of color applications, oscillating between the expressive and the graphic. Amrani clearly sets to his canvases with gusto, employing broad, aggressive brush strokes with flat and restrained dabs of color. His most notable skill is his ability to convey his ideas in a cohesive and engaging manner while constantly proffering numerous points of stylistic, artistic, and cultural reference.

The Artists’ House has a longstanding tradition of bringing in new members to the Jerusalem Artists Association on an annual basis and featuring their works in its seasonal curtain raisers. This year’s inductees include Sara Benninga, Yael Boverman-Attas, and Noga Greenberg.

It is apparently easy to grasp the aesthetic cord that joins Benninga’s and Amrani’s offerings. There seems to be a melee of shapes and figures in each artist’s works. Yet appearances can be deceptive. While their canvases may be busy, the composition and underlying force of each hail from very different avenues of thought and junctures along the artistic time line across the millennia.

While Amrani feeds off contemporary cultural phenomena and disciplines, including animation, Benninga dips into deep historical seams while combatively defying the constraints they might place on her sphere of operation and creative ethos.

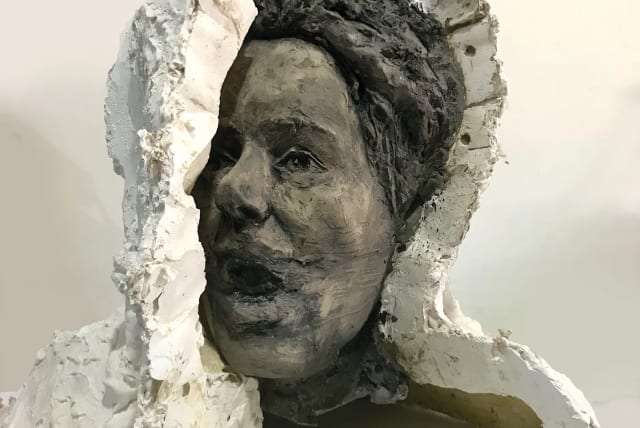

Benninga, who lectures at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design and at Tel Aviv University, fuses her paintings with plenty of hooks that help you get up close and peer quizzically at the maelstrom of forms, figures, and body parts that pop up all over the place, in all kinds of unexpected positions and postures. Gesticulation often seems to be name of the game, but then you catch another complete figure that exudes a more pastoral tranquil vibe.

There is a definite sense of drama, but this is offset by more opaque forms of expression, suggesting more enigmatic presentational choices. Benninga also opted for a bare bones chromic approach and keeps a steady hand on the evolutionary tiller. “These are paintings,” she says, stating the obvious, although quickly adding she takes the base discipline far beyond its primordial baseline. “These are based on an experimental technique I have developed over the past year.”

As befits all new philosophical avenues, Benninga aims to ply her own individual course through the artistic domain. “I have painted in oil before, but here I was looking to challenge the oil but also to find a way to tell a complex tale in my work. This technique helped me to do that.”

She gave me the lowdown on the stratified nuts and bolts. “I draw with charcoal and dry pastels. I seal that in the canvas, and then I paint with acrylic; and after it all dries, I use oil.”

The upshot of that layered approach is a beguiling aesthetic style that gives an elemental impression while clearly comprising a narrative of numerous parts and points of reference. Then again, one can find manifold story lines and standalone figures that, nonetheless, maintain dialogue on some level or other. Femininity, sexuality, personal experience, and psychological tension all shimmer and crouch ready to pounce or, at least, leave their imprint on our mind.

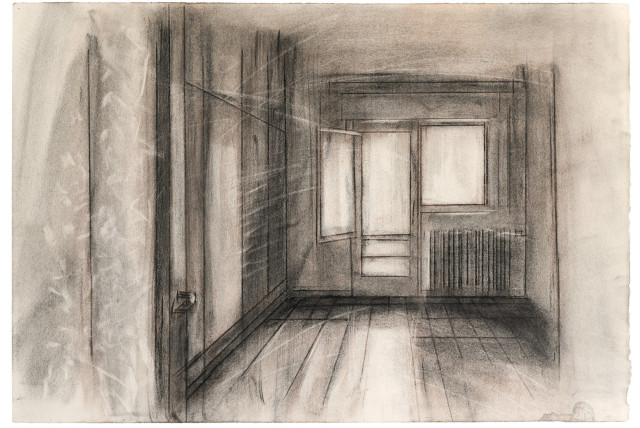

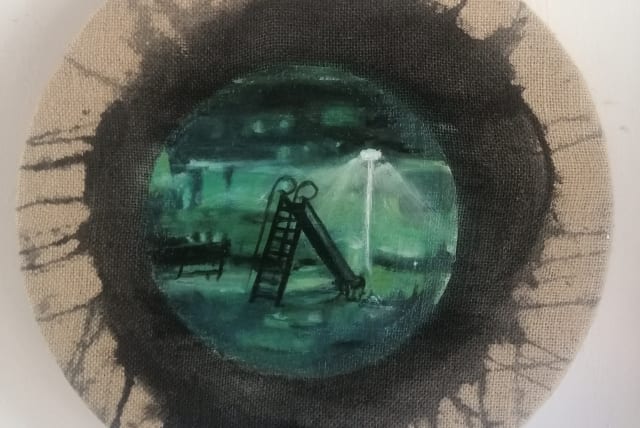

The works in Boverman-Attas’s Hallway series come from a far more personal backdrop and are fueled by her memories of her parents’ apartment in Rehavia, her childhood home. She imparts that sense of early years lived, loved, and traversed in her largely monochromic drawings that almost take you by the hand and lead you through the vacated spaces of the residence, now physically abandoned, although the spirit of the occupants and their relationships continue to echo there.

Here, too, there is a sense of latent emotion bubbling just under the surface. On a basic visual level, Boverman-Attas depicts comforting yet powerfully evocative strands of light, including of the physical and – by natural extension – personal reflective kind.

Proportions, dimensions, and seemingly empty spaces are all presented to the viewer per se but still resonate with the aggregated dynamics and quotidian experiences that filled and colored the physical structure over the familial years.

There is a loaded substratum to Hallway. “This comes from a series I called Silence in Three Languages,” explains Boverman-Attas, “a thundering silence.” That references her antecedents’ Holocaust background. “My grandmother would come to visit and speak Yiddish with my father, Polish with my mother, and Hebrew with us. There were other languages, too. But in all those languages, the things that were not said filtered through.” As they do in Hallway.

The third new member, photographer Noga Greenberg, focused on the minutiae of domestic existence in her Ordinary Days series. The pictures were spawned by three years of observation, which take in the enforced inward-looking, and physically and emotionally strangulating, dark days of the coronavirus lockdowns. We get close up to specks of dust, gently peeling wallpaper, and droplets of everyday life – and an overriding sense of what home means for the Greenbergs.

Spotlight on photography

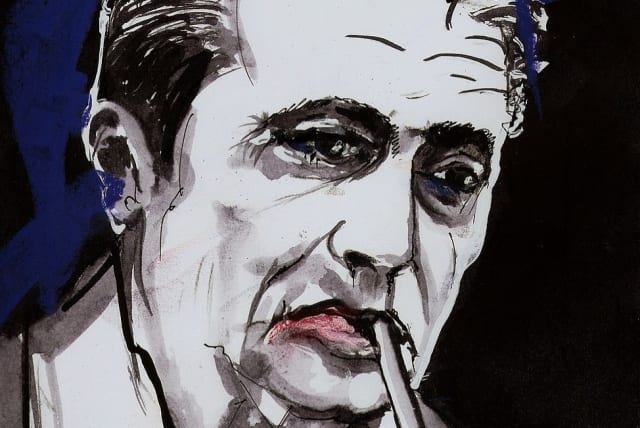

Photography also plays a leading role in photographer, painter, and art therapist Adi Bezalel’s Wounded Healer exhibition, curated by Tal Frenkel Alroy, on the middle floor of the building. Bezalel deftly fuses two contrasting mediums by using photography, which historically developed from painting, as a point of departure for her painterly practice. Gouache serves as a sensitive medium for developing still life photographs, as Bezalel treats the images as if they were an open wound, healing them through innocent-looking painting.

“‘Wounded healer’ is a key concept in Carl Gustav Jung’s psychoanalytic theory,” Frenkel Alroy notes. “Its importance lies in the understanding that the therapist heals the patient’s wound through identification and by touching his/her own wound.” That concept resonates all too powerfully in these parts these days. ❖

The current exhibitions close on December 2.

For more information: art.org.il/en/current-exhibitions/