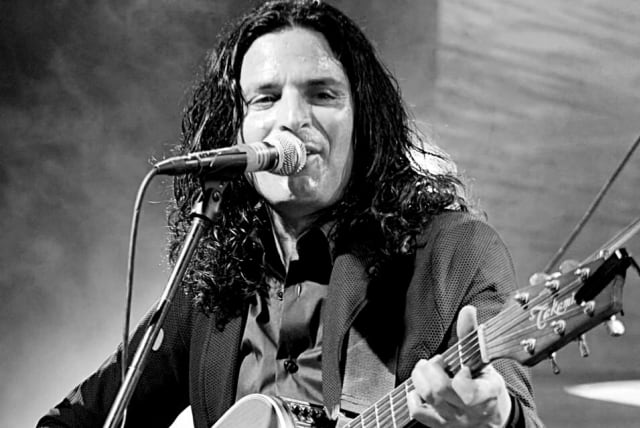

Art hath healing powers. As we continue to lick our physical and emotional wounds, increasing numbers of artists, across all sorts of disciplines and fields have begun to roll out some of their creations in a bid not only to express their own thoughts and feelings about the current dire straits but also to enable us to feed off their work and possibly gain some reflective respite from the doom and gloom.

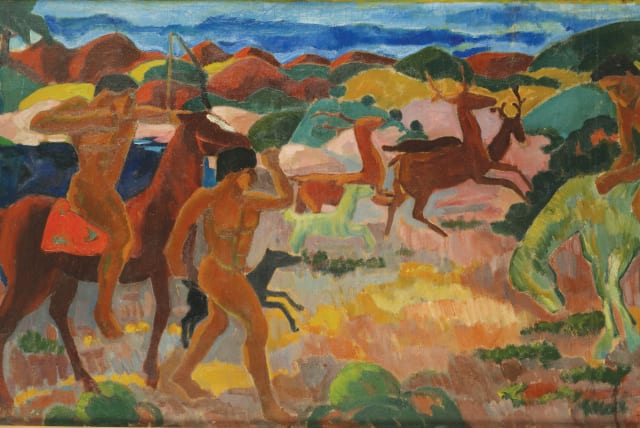

Battlefield exchanges have provided many painters with inspirational raw material over the centuries. There’s Turner’s marine-set Battle of Trafalgar from 1824; the tapestry-like Battle of San Romano by Italian Renaissance artist Paolo Uccello; and Goya’s evocative Third of May 1808, from 1814. And who could forget Guernica, the iconic anti-war statement by Picasso created in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War?

Rina Peled believed that some of our own artists could also do something about conveying some wartime sensibilities to the public. The seasoned Jerusalem-born artist is a member of the professional collective that forms the Agripas 12 gallery, stashed away in the quaint back alleys betwixt the shuk, Jaffa Road, and King George Street.

She shared her thoughts with fellow gallery member Oded Zaidel, and the Returning group exhibition duly came to be. The show opened on December 21 and is due to run through to the end of January.

Peled says she and her cohorts felt compelled to put their emotions and musings out there. She says Returning is “an exhibition in which everyone expresses his or her feelings in the face of reality at this time. It is precisely in the midst of chaos and pain, when we are overwhelmed with feelings of insecurity, fear, and frustration, that we must offer ourselves and others the consolation of art.”

It is a multifaceted offering covering a multitude of aesthetic and conceptual bases, taking in video art, installations, paintings, photography, and etchings. Curators Peled and Zaidel have done a good job with placing the works around the white walls of the gallery, leaving plenty of air between them without overdoing the dimensional spread. And the juxtapositioning of monochrome and colorful creations and works of different disciplinary stripes, textures, and volumes has been achieved with a subtle but sure touch.

The exhibits run the gamut of expressive presentation. There are works that beg some thought and contemplation to eke out the underlying message, while others are more feral and immediate. Ariane Littman’s two-parter spells out the emotive state of affairs in no uncertain terms.

An art exhibition amid the trauma of the Israel-Hamas war

The larger of the two components features an old suitcase stuffed full with pristine, rolled-up white gauze bandages, with a diminutive enamel bowl daintily placed on top. On closer inspection, you notice the white bowl has hundreds, possibly thousands, of numerals painted on it in shades that vary between dark red and black. The tightly packed numbers are repeated copiously around the circumference of the vessel – 7.10.23. – the date that is forever etched into our hearts and the national psyche.

THE INK shade Littman uses in Suitcase 2023 leaves no room for doubt. This is blood – blood that oozes, drips, and flows – the blood of the youngsters murdered at the Supernova music festival, of the hostages and the moshavniks and kibbutzniks in the Gaza envelope, and the blood of our soldiers who continue to fall in battle.

Littman, an interdisciplinary artist and lecturer at The DAN Department of Creative Human Design, Hadassah Academic College in Jerusalem, pulls no punches. She has been highly active on the local art scene since the Second Intifada and the Second Lebanon War, addressing issues of conflict and national woes. Bandages came into her creative purview after her daughter suffered serious burns in 2009.

Suitcase 2023 has another, Holocaust-related, subtext to it. “The suitcase, bought at a flea market in Berlin, is related to an installation I did in Berlin in a gallery that was once the house of a Jewish family who was forced to sell for nothing and flee,” Littman explains.

Like the rest of the Agripas gang, it took Littman a while to resurface from the depths of despair and despondency after October 7. “After the Black Shabbat, I was paralyzed,” she recalls. “The trauma was so great that I wasn’t able to create anything. I asked myself whether there was any room for art, and it was only a month and a half later that I went back to my studio, and I created works that connect to the war.”

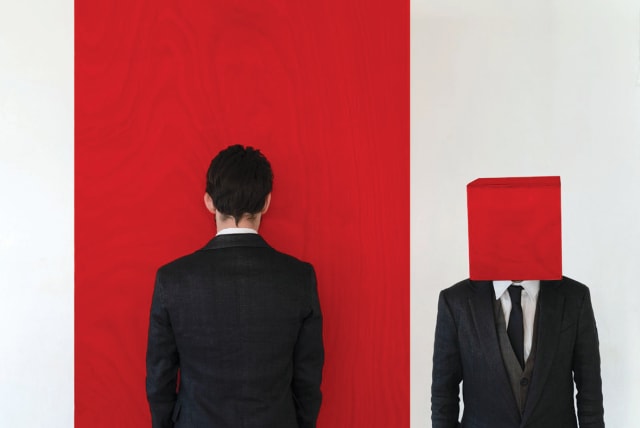

The same could be said of her fellow exhibitors. They express – in their own way, format, and discipline – their sadness, their ruminations on the meaning of life, and the unfathomable savagery that was wreaked on us. Photographer Doron Adar’s Blood of Anemone #101 is an alluring tetraptych based on the titular flower, which, naturally, puts one in mind of blood. Adar cleverly navigates his way through permutations of black, white, and red.

In the top left frame, the flowers are set against a dark, black-gray, grassy substratum, which accentuates the brightness of the petals. You get a similar effect in the print to its right, although in brighter shots the flowers seem to be more detached, as if hovering ethereally in some physical or emotional void.

The human element is conveyed by a couple seated in the meadow. Are they lovers? Siblings? Are they just basking in the bucolic tranquility or are they comforting each other in the wake of some tragedy? Adar also plays the light-shade balancing act deftly, and allows us to complete the colorful picture ourselves in the monochrome photograph.

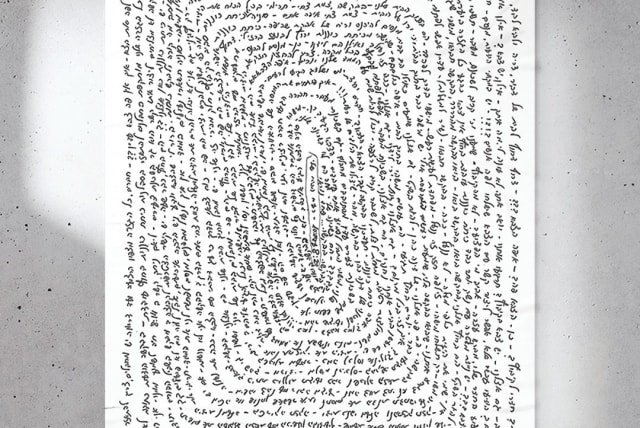

THE CURATORIAL continuum sets off delicate works against creations that grab you and demand you spend some time with them. Yoram Blumenkranz’s diptych clearly pertains to the former. At first glance, his contribution appears to comprise thread delicately sewn into cloth or possibly pencil dashes that ebb and flow airily to create a delightfully subtle sense of airiness and natural dynamics.

In fact, Blumenkranz went for a diametrically contrasting raw material – plain old office staples. Somehow he manages to convey the sense, and something akin to the actual touch, of a far softer, more supple means of visual communication. You can almost feel the air eddying around the wheat sheaves and palm tree in the pictures. The crisscross tree bark of the trunk is simply delectable.

Blumenkranz clearly had dissonance and the violence down south in mind when he crafted the plywood base work. He bluntly describes it as “a targeted landscape,” adding that all his component choices leave their imprint not only on the corporeal nature of his work; they also add their mark on our perception of our surroundings.

“It is impossible for things not to leave an impression,” he posits, before reeling off a list of everyday incidents that change the physical state of play and tweak our sensibilities. “A cup is dropped into a sink, blood on a cutting board, a toe against a door frame, a forgotten key, a swallowed bank card, a threadbare pocket, and a shekel coin that slips through the fingers.”

That’s quite a litany of quotidian mini-disasters that could throw anyone off their stride. Blumenkranz waxes a little poetic. “A sudden pulse and a slip, and gunfire tears the peace of the street asunder, attaching a piece of paper to a noticeboard about his [own] death. The whole landscape is shot, and the plywood takes it all,” he adds. Appearances, it seems, can be a little misleading.

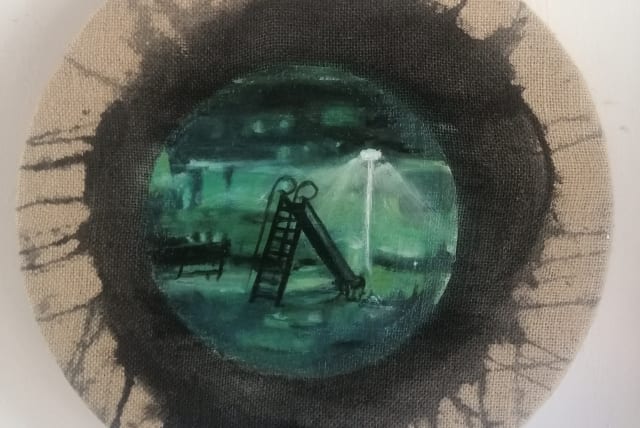

Bitya Rosenak’s spread also follows a monochromic line and references her predilection for fabric-oriented designs and textures. She says she started out on the series prior to the war. The works subsequently took on a new, darker meaning. “As usual, I experimented with different materials. This time I examined how paint reacts with milk,” she explains.

The exercise delivered intriguing results. The exhibit gives the impression of a combo of Rorschach test images augmented by delicately drawn lines. It makes for beguiling and thought-provoking viewing. “I pondered what they meant to me. Then the war came, and they immediately turned into explosions for me,” says the artist about the splashy blot-like shapes that look a little like dancers shaking a muscular leg or two. The linear element followed. “I consolidated that sense by adding lines which accentuate the feeling of powerful explosions moving up and down.”

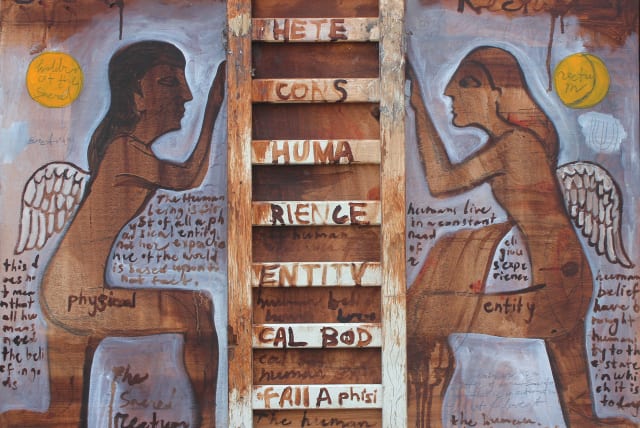

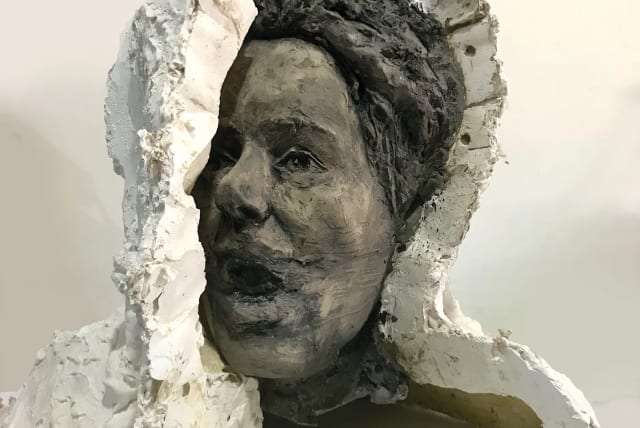

VISITORS TO the gallery will, no doubt, get the air of national trauma, but they will also have plenty to spark their emotions and appreciation of well-crafted aesthetics. Some impart the dark zeitgeist more palpably than others. Take, for example, Penina Shalvi’s totemic figure, which seems wary and frightening in equal amounts. Shalvi references the subconscious in her artist notes and borrows from feted psychologist and psychoanalyst Carl Jung to support her creative venture.

“Everyone carries a shadow, and the less it is embodied in the individual’s conscious life, the blacker and denser it is,” Jung argued, adding that untended emotional baggage can cause problems. “At all counts, it forms an unconscious snag, thwarting our most well-meant intentions.”

Ruth Schreiber’s diptych provides the most direct reference to the war and personal emotional shock waves. The double collage exhibit comes from a six-part series of self-portraits created between October and November this year. They feature images lifted from news reports about the war, betwixt pictures of the artist’s grandchildren. “I try to protect them from the destructive news, but at the same time, I also need to follow the news myself.”

That is a challenging dichotomy indeed, although one may question the necessity to constantly stay abreast of developments here. Be that as it may, Schreiber does the evocative and emotive business, particularly with the deft inclusion of Edvard Munch’s iconic Scream in various guises.

Peled also weighs in with a series of wood etchings that manage to conjure up all sorts of feelings and thoughts about the way things stand. In recent years, she has increasingly drawn on her own surroundings and the scenes she catches as she moves around the capital. She says she likes the elbow grease demands of chiseling away and scoring pieces of wood as she creates images that ebb and flow between the figurative and the abstract.

She spells out her take on the ongoing violence in these parts. One of her four exhibits at the gallery, a fetching abstract work, comprises two black-brown rectangles, which have been given a good going over by Peled. They are connected by a splash of red – a frank reference to bloodshed – with the penciled-in words “bloody war” repeated numerous times in the center. The color scheme also dovetails neatly with Adar’s neighboring anemones.

Working as a collective clearly offers the advantage of having your own solo spot on a regular, rotational basis. But when the members come together in a group setting, the synergic rewards come through loud and clear. Returning is an emotive tour de force that offers compelling viewing and a chance to take a different vantage point on the way things are panning out here. ❖