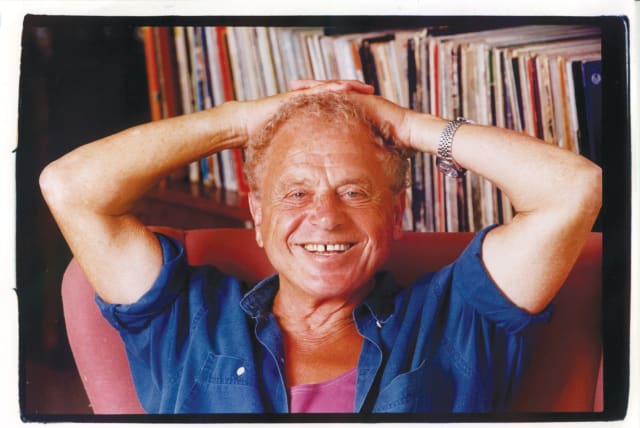

Ariel Wardi is one of those priceless characters you rarely meet.

It is not merely about his longevity here on terra firma. He exudes an alluring spirit of geniality, benevolence, and hard-earned street-level wisdom. There is an unassuming gentleness about the man that immediately stops you in your tracks. Perhaps those are the attributes one needs in order to take on a hands-on project of the enormity and stamina-testing dimensions that has engaged Wardi’s physical, creative, and emotional focus for three decades and counting.

Entering Wardi’s workshop is like stepping into an Aladdin’s cave. Once in a while, you come across something that gives you a palpable sense of an extraordinary experience that you don’t come across too often. At the age of 94, Wardi is happily at it, popping along daily to his studio-work space in Talbiyeh and religiously working away on some new creation or other.

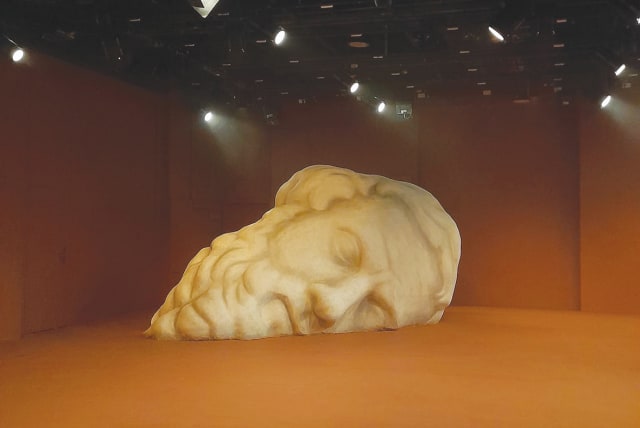

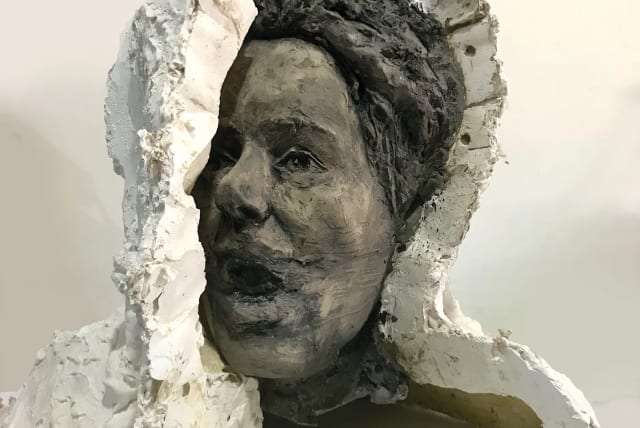

I was met with a “Welcome to the Small Room” greeting, a warm smile, and a firm handshake. I had been given some idea of what I would encounter when I got to Wardi’s private work domain from Hadassah Goldvicht, an internationally acclaimed artist who worked closely with the nonagenarian print expert on devising “The Private Press in the Small Room” exhibition at the Mamuta Art and Research Center at Hansen House.

The show opened last week – postponed, like numerous other cultural events, by two or three weeks due to the ongoing war – at the cloistered ground-floor display facility which makes a habit of proffering the work of left-field artists who bring substantial added value to artistic life here. The exhibitors also tend to be artists who are routinely sidestepped by the mainstream arts sector folk.

Wardi is one of a kind. He made a living in the printing and graphic design business, rising to the upper echelons of the profession, as well as heading the Print Studies Department at Hadassah Academic College in Jerusalem. When he retired 30 years ago, the dynamic then-63-year-old was not about to sit around watching the cows stroll home. He soon got going with a fellow retiree professional and dived headlong into the world of boutique-run printing. And though the partnership did not last long, Wardi steamed ahead, even creating some of the fonts he used as he fed off the good old movable-type printing method invented by Johannes Gutenberg in Mainz, Germany, in the mid-15th century.

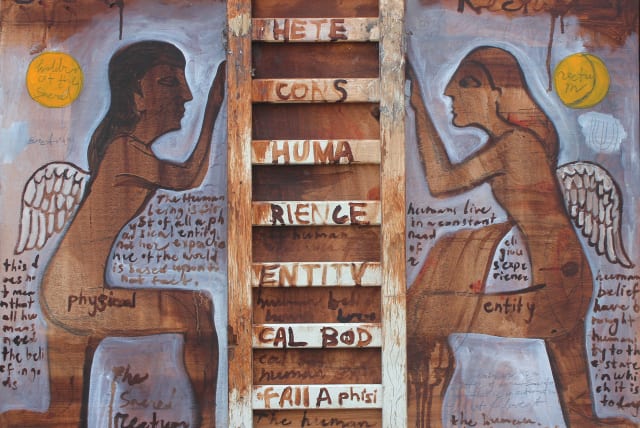

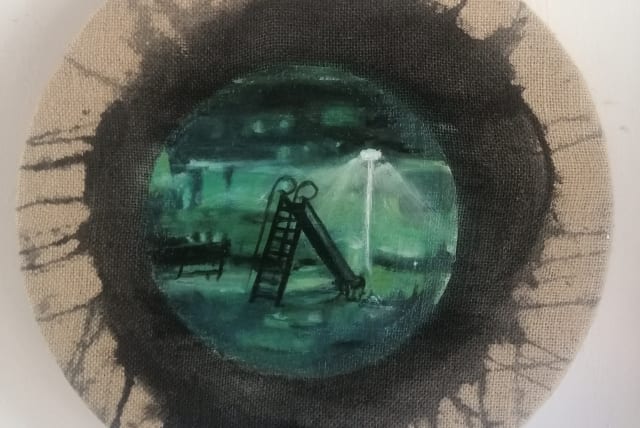

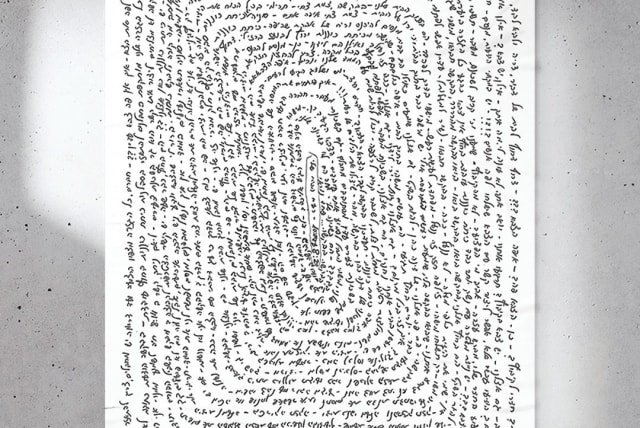

The Small Room is jam-packed with singular tomes Wardi has created over the years, minus a few volumes that now temporarily reside at Mamuta. The books are beautiful works of art, even though Wardi shuns the “artist” epithet himself. The letters he used to print sections of the Book of Job and various Psalms are a joy to see, and there are several books of poetry he wrote himself. The man seems to have little in the way of artistic disciplinary bounds.

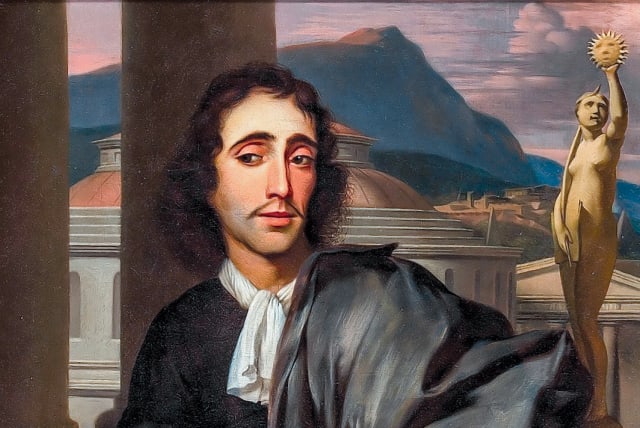

“Renaissance man” would perhaps be a half-decent term to use in describing Wardi, who effortlessly leapfrogs boundaries between fields of creative expression. Take, for example, the way in which he translates the textual content of some of his one-time productions into Morse code. The video clip in the exhibition of Wardi reciting verses from Job in sonic dots and dashes, created by Goldvicht, is riveting. And the fascination factor is enhanced by his use of a long pencil as a pointer, much as a baal koreh (synagogue Torah scroll reader) holds a yad as he or she reads from the weekly portion on Shabbat, Monday, and Thursday.

Bookmaking in the virtual age

It is intriguing to note that Wardi began his solo venture into the physical machinations and aesthetics of printing and bookmaking just as the virtual world was taking over. Apple Mac computers had come into their own in the mid- to late-1980s, and the intangible was rapidly replacing the corporeal as the digital revolution irreversibly changed the way we live and create.

There is something primordial and rudimentary about the way Wardi goes about his business as he doggedly continues to bring the aesthetic mists of the past into the here and now. But thus far, that had been his own exclusive personal joy as the tomes he lovingly printed and bound, often employing elemental constituent materials such as sand and soil as jacket cover material.

That was until Goldvicht got in on the act. Her vast eclectic oeuvre, which has been exhibited around the world – such as the Israel Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Lisbon, and the Jewish Museum in New York – features numerous references to letters and the written word, so the Wardi synergy was a snug fit.

Even so, getting the show up and running was not an entirely smooth ride. “We worked on it very intensively, Leah, Ada, and I, and Naama,” Goldvicht notes, referencing her partners in the Small Room undertaking – Mamuta director Leah Mauas; Mamuta projects manager Naama Mokady; and renowned graphic designer and curator Ada Wardi, who is Ariel Wardi’s daughter and celebrated book designer. Wardi Sr.’s voluminous stacks of tomes include a book created and designed by Ada about pioneer Israeli typographer and artist Moshe Spitzer, who serves as a source of inspiration for the Jerusalemite nonagenarian.

Embracing different disciplines

One of the most compelling sides to Wardi’s work is his ability to embrace different disciplines and to ebb and flow between them in seamless fashion. That partly stems from his work as a naval wireless operator when he took part in trying to get Jews into pre-state Palestine and slip them past the British patrol boats. The exhibition offers the visitor a glimpse into that inclusive, non-generic approach and may even help us to adopt a more accommodating view of art as a whole. Letters, aesthetics, and different forms of presentation are all one and the same for Wardi.

Goldvicht says there is nothing premeditated about Wardi’s interdisciplinary line of artistic attack. “He doesn’t see it that way,” she explains. “The sound side of the exhibition is something strange that came out of our encounter.” Each artist followed their own avenue of aesthetic understanding in putting together the layout at Mamuta. “The separation between the actual print work and the abstract video work, with sound, that I do, was very meaningful.”

During our conversation, I found myself repeatedly apologizing for using the “artist” epithet for Wardi. It wasn’t easy. While he clearly produces work that is highly pleasing to the eye, there is also the down-and-dirty, physical side of the business. I tried not to attach the “art” title to what Ariel does.

Considering his determination to skirt a wide berth around all art tags, it is somewhat surprising that Wardi agreed to collaborate with Goldvicht at all. Additionally, many of the fonts and letters he so painstakingly and lovingly created over the years, and the tomes he printed, sewed, and bound, had never seen the light of day before. Until now, they had all been stacked up in his Small Room workspace as he went about his altruistic creative work in his own physical and emotional bubble. It is safe to say that not many people, if any at all, had any idea what was going on every single day behind the door to the ground-floor apartment on Hanassi Street a stone’s throw from the Museum for Islamic Art.

Art during wartime

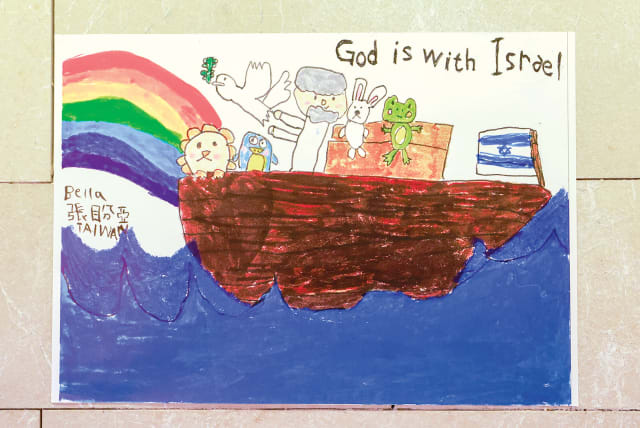

Goldvicht sees a highly pertinent thread to the exhibition at this most challenging of times. “This whole work is a voyage. I think it is very poignant that these works are being shown to the public. It is a sort of a reset, getting back to basics – asking questions about who and what we are. Let’s start with aleph again, and then we’ll know how to assemble more words. Then maybe we will discover something new in our identity.”

The exhibition was originally due to be unveiled on October 12. With the horrors of the Hamas massacre and the war in its early stages, that was never going to happen. “We thought that it was [meaningless],” Goldvicht says. But, as we gradually try to return to some semblance of normal life, an increasing number of cultural activities have started taking place, offering us some respite from the doom and gloom.”

Mamuta’s director Leah Mauas got that and was keen to get the exhibition back on track. “After a few weeks, Leah asked us to come over and said we should try to put the exhibition together. We felt we were playing with make-believe,” Goldvicht smiles. “We laid the show out, and suddenly we saw its beauty. There were also the Morse code calls, like war calls. Suddenly it all looked just right.”

The circumstances, Goldvicht feels, required a radically new approach, a complete break from previous patterns of thought. “It is as if where the words end, we need to deconstruct, re-identify the basic forms and start all over again. Our entire reality was turned on its head. We need to relearn things.”

Indeed, there is something refreshingly elemental about letters, although, these days who uses a pen to write, let alone create fonts and unique books?

The communicative fallout of Wardi’s job over seven and a half decades ago, says Goldvicht, can help to make things a little clearer. “Words can be ambiguous, but there is something more precise about Morse code.”

There are several references in the exhibition to Wardi’s former naval duty. The video work with the yad features Wardi reading from the biblical book of Jonah, who spent three days in the belly of a whale en route to this part of the world. The marine common denominator is obvious, but there are also sentiments in deeper places that strike an important chord. “Something comes up from the deep,” Goldvicht notes. “All Ariel’s ideas and my ideas over the past two years waited for this moment to come together in the exhibition.”

Meanwhile, Wardi keeps his nose to the grindstone. For a man like Wardi who has worked clandestinely for so long, I was pleasantly surprised by his eagerness to show me around. “This is the printing room,” he says, introducing me to a compact printing machine he has been using for over 30 years. “There are only a few machines like this in the country. They came to Israel in the 1960s.” Needless to say, Wardi makes good use of his Vandercook press. He says they enjoy a good relationship. “It takes good care of me,” he laughs. No doubt, the 94-year-old craftsman returns the favor.

The magic in overcoming obstacles

Even with Wardi’s meticulous caring approach to the machine and the printing process, there are always challenges to deal with. He says that is all part of the fun. “It wasn’t an easy transition [from his daytime job after he retired]. I found a machine, but there weren’t any letters.”

But that wasn’t going to stop Wardi, with his decades of experience in the printing field. “I had to make the [movable] letters myself. I didn’t have a choice. I think there is magic in overcoming technical obstacles, learning how to do things. You start to deliberate; it is frustrating, but it grabs you. There were problems that took me six months to solve.”

Steady hands and eyes are the order of the day if you are going to produce your own letters and create your own one-time books, and Wardi was no spring chicken. “It took me 10 years to make the letters. I started from large fonts and gradually reduced them. I started from 72 points and got down to nine points,” he adds. “Each time, I used a different technique.”

As his eyesight weakened, he eventually turned to a different aesthetic. “After 10 years [of designing and printing letters], I could no longer see well enough, so I moved into [artistic] prints.” Some of those feature in the Mamuta show.

The exhibition is a salute to the talent and dogged determination of a craftsman from a different era who exudes a gentle demeanor but also a steely hard-earned core. This is an event to savor. ❖

The ‘Private Press in the Small Room’ closes on December 29. For more information: mamuta.org/?lang=IW